History of the Doge's Palace in Venice

The history of the Doge's palace in Venice begins in medieval times and continues with numerous extensions, renovations and demolitions aimed at adapting the building to the new needs of the city and in particular to the need to give a seat to the governing bodies that, increasing in number, began to complement the doge in the administration, depriving him of certain powers and decreasing the space at his disposal.[1]

In 810, after Venice had become capital of the Serenissima, taking the place of Eraclea and Metamaucum, the seat of the doge was built there, probably in the form of a fortified and turreted palace, soon flanked by a basilica.

The complex remained essentially unchanged in its appearance until the 12th century, when, with the dogate of Sebastiano Ziani, an era characterized by numerous renovations was inaugurated, involving all three wings. In the southern, western, and eastern wings, work began before 1340, in 1424, and in 1483, respectively, in the latter case as a result of a fire that was to be followed by two others, which resulted in the destruction of a great many works of art, promptly replaced by the work of the leading Venetian masters. Having built the New Prisons and renovated the first floor between the 16th and 17th centuries, the palace was no longer the subject of major works, but rather suffered damage that led to the removal of numerous works of art.

With the annexation of Venice to the Kingdom of Italy, the building came under the latter's jurisdiction and became a museum venue, a function it continues to perform by housing the Civic Museum of the Doge's Palace, part of the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia (MUVE) and visited by 1,319,527 people in 2012.[2]

First locations[edit]

Eraclea[edit]

According to tradition around 697 the Venetian refugees who had taken refuge in the lagoon elected Paolo Lucio Anafesto their doge, and it became necessary to build a house to become the seat of government. Tithes were instituted and a number of serfs were granted to the doge. The doge's seat was placed in Eraclea: there the first Doge's Palace was built, the form of which is unknown today as its location is unknown and no ruins remain.[3] The palace, decorated with marbles of oriental origin, must have looked very different from the present one, and much more unadorned.[3][4] Due to the continuing disputes between Heraclians and Equilians and the killing of Orso Ipato, the third doge, dogal functions were briefly delegated to an annually elected magistrate.[4]

Metamaucum[edit]

The transfer of the doge's seat to Metamaucum, a fortified city with a flourishing economy due to cultivation corresponding to modern Malamocco, took place under the rule of Teodato Ipato, son of Orso:[3] this choice is said to have been made because he accused the inhabitants of Eraclea of having killed his father.[4] A second palace therefore had to be built, as the new doge, a native of Eraclea, had no home of his own in the new city. After sixty-eight years and the succession of five doges, Agnello Participazio was elected, who decided to relocate the ducal seat again since Metamaucum had turned out to be an unsafe city.[5]

Transfer to Venice[edit]

The place chosen for the building of the new doge's seat was the area of Rivoalto, distant from the sea and separated from it by several islands and therefore safer. This relocation can be dated to the year 812. The new palace, called palatium ducis, was built around 814 near the church dedicated to St. Theodore, later replaced by the basilica of St. Mark after a fire,[5] on land owned by the doge.[6] The building site was completed under the dogate of Pietro IV Candiano: no trace remains of that construction, erected in the same area now occupied by the Doge's Palace, but it is likely that the building was made (at least partially) of stone and had four watchtowers at the corners and a courtyard in the middle.[6][7] The fact that the doge's house was extremely fortified[1] is attested firstly by the fact that it managed to withstand the revolt that broke out in 976 against Doge Pietro IV Candiano,[8] and secondly by the fact that Doge Pietro I Orseolo was able to personally bear the expenses of rebuilding the palace after it had been hit by fire, a sign that the damage must not have been excessive.[9] The reconstructed building was characterized by the presence of a fortified central body with angular towers, surrounded by water, traces of which can still be glimpsed in the layout of the loggia plan. These structures were characterized by the preponderance of rooms dedicated to the doge over those that were to house the other magistracies: this is indicative of their subordination to that of the leader and political head of the republic.[1]

Otto III, Henry IV and Henry V in Venice[edit]

Twenty-two years after the aforementioned fire, Otto III decided to travel to Venice to meet with Pietro II Orseolo, son of Pietro I.[10] The doge prepared an apartment for him in the eastern tower.[11] The palace was equipped with at least two towers, one western and one eastern, placed at either end of the facade facing the lagoon.[11] Chronicles of the time also describe the emperor's appreciation of the palace's interior decorations, equal perhaps only to those of imperial residences, which had been perfected by the then Doge Pietro II Orseolo.[11][12]

From 998, the year when Otto III was a guest at the Doge's Palace, to 1105 there are no sources that give precise information about the renovations undergone by the building's factory.[13] It is, however, probable that Domenico Selvo, doge between 1071 and 1084, oversaw the decoration of the palace as he himself gave a strong impetus to that of the adjoining church.[14] Nevertheless, all these decorations were destroyed in the subsequent restorations and in particular by the fire of 1574: as Francesco Sansovino recalls, "the doors of Parian marble columned and figured with great skill" that were present in the hall of the Four Doors were destroyed.[14] The next doge Vitale Faliero had the opportunity to host Emperor Henry IV in the palace, who, being very devout, had come to the city as the body of Mark the Evangelist was there.[15] Under the dogeship of Ordelafo Faliero two fires occurred at the distance of two months, approximately around the year 1105, which destroyed various city buildings.[15] The more tragic of the two was probably the second, which broke out due to lightning and spread due to strong winds.[15] The damage that this fire caused to the basilica and the palace is only hinted at by historians of the time,[16] who do not even describe the renovation overseen by the doge, which was concluded before 1116, the year in which he hosted Henry V.[16]

Expansions[edit]

The columns of St. Mark's Square[edit]

According to chronicles of the period, the doges who ruled between 1117 and 1172 did not carry out renovations inside the palace,[17] but it would date back to that time the arrival in Venice of several marbles from the East, including the columns that characterize the small square in front of the palace, which possibly arrived from Constantinople in 1172, that is, just after the death of Vitale II Michiel. However, the date of the arrival of the columns should more likely be dated to the dogate of Domenico Michiel: it would have been the belonging to the same family of the two doges that misled the writers of the time.[17] This second theory is supported by several elements: first, the dogate of Vitale II Michiel was characterized by the outbreak of strong contrasts between Venetians and Byzantines, and the latter would never have allowed the removal of the columns;[18] secondly, Francesco Foscari, in stating that "those columns stood for many years on the ground, no person being found whose disposition was sufficient to raise them up", suggests that a fair amount of time must have passed between their arrival and their erection, which would be unlikely if their arrival dated to the end of Vitale II Michiel's dogate or the beginning of Sebastiano Ziani's.[18] The arrival of the columns in Venice must therefore have occurred around the year 1130.[18]

Sebastiano Ziani[edit]

During the dogate of Sebastiano Ziani, elected in 1172, the complex underwent a first major renovation, which transformed the original fortress into an elegant complex consisting of two buildings, one facing the lagoon and the other the small square, built according to the stylistic features of Venetian-Byzantine art,[1] in accordance with the main architecture contemporary to it.[6] It is probable that the Lombard Nicolò Barattiero, the one who erected the two columns and made the Rialto Bridge in a primary form, played a primary role in its realization, and that his style was influenced by elements of the Lombard tradition.[19] Just after the completion of the building site, Pope Alexander III and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, who had reached a pacification through dogal intermediation, stayed in Venice. In particular, it is known that the emperor stayed in Venice for two months, sojourning at the palace.[20]

Exterior renovation project[edit]

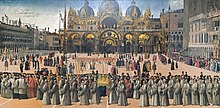

According to modern historians toward the small square stood the palace of justice, characterized by a large portico on the ground floor, an open loggia on the first floor, and offices on the second floor, while toward the pier stood the palace for assemblies, which extended from the small square to the present Ponte della Paglia.[6][21][22] For the reconstruction of the original design one can rely on the traces contained in Bellini's work Procession in St. Mark's Square, in which the Procuratie Vecchie and the Ospizio, on the left and right sides respectively, feature a characteristic portico, which must have been present in the Doge's Palace whose upper floors, decorated either by floral frescoes, stuccoed bands, or roundels in the same material, can be reconstructed with less precision, asserting that perhaps the first floor was characterized by small loggias and windows and the second floor by round arches with simple capitals and crowning spires.[22]

Interior renovation project[edit]

The complex was home at the same time to private dwellings, public offices, private businesses, and prisons. No sources remain that attest exactly to the layout of the rooms within these buildings. However, one can speculate by comparing documents and other non-technical evidence. Specifically, the building toward the lagoon, or town hall, would have housed:

- on the first floor the double-height Great Council Hall, surrounded by a portico, the location of which is known from documents of the time attesting to the fact that it was connected with the courtyard[1] and flanked by other smaller rooms, including the chapel of St. Nicholas, facing the canal;[22]

- on the upper floor the rooms of the Avogadori, the Censori, the Lower Chancery and the Quarantia, the latter, copiously recorded in the historical archives because in the latter the councilors met during voting, connected by narrow corridors to the larger room on the first floor;[22]

- on the second floor other rooms dedicated to administration, including the upper ducal chancery.[22]

The building toward the present square, known as the Palace of Justice, once fronted perhaps by a canal,[23] would have housed:

- on the first floor public offices, facing before the fortified rampart, as well as stores and apartments rented to private individuals, connected with the waterfront;

- on the second floor the offices of judicial offices, such as that of the Lords of the Night, the Avocadores Comunis, the magistrates of the Piovego, and the Cattaveri;

- on the last or penultimate floor the prisons, moved from 1297 to the first floor, freeing rooms occupied by private individuals.[22]

Traces of the latter building still remain today: fragments of basement in Istrian stone and some terracotta herringbone pavements.[21]

In addition to the renovation of the palace and the adjoining church, Ziani was also the architect of the enlargement of Piazza and Piazzetta San Marco, which he surrounded with luxurious buildings. While retaining the angular walls that characterized the palace and the fortified entrances to the square, the doge also had the crenellated wall surrounding the square demolished,[1] built in the 9th century to protect the city from invasions and whose presence is attested by a map of Venice dating back to the 12th century. The enlargement of the square and the demolition of the wall allowed the two large columns to be raised on the sea front.[24] Some elements, including the layout of the increasingly cramped doge apartments, remained unchanged before and after the operation.[1]

Course and purpose of the renovation[edit]

The expansion of space was related to the need to provide a home for the many organs and offices that were springing up at the time,[6] while the shift from a fortified structure to a civilian, open architecture testifies to how the defensive necessity was no longer so keenly felt, since, as the domains of the lagoon city expanded, the boundaries of its possessions were increasingly distant from the centers of power.[1]

Regarding this operation, Francesco Sansovino recalls that "not only did Ziani renovate it, he also enlarged it in every respect."[24] However, the account that is given by historians in relation to this renovation work is by no means accurate. It is probable that, considering that the aforementioned walls also bordered the canal placed today along the eastern façade of the palace, there was between the ancient palace wall and the defense wall facing the canal a space suitable for light to enter the interior of the palace windows: with the demolition of the wall, it was therefore possible to occupy that space.[25] The work lasted from 1173 to 1177.[20] In order to carry out further expansion, land belonging to the nuns of the church of San Zaccaria, which extended as far as the church of Santa Maria in Broglio, was purchased. To carry out the expansion, several wings of the first factory, those facing the canal, the lagoon and the small square, were demolished. On the other hand, the wing facing the church was not torn down, as that was where the dogal rooms were located and at the same time it would not have been possible to build new rooms in that area. It is likely that the enlargement was so substantial that the previously larger square facing the lagoon was reduced to a mere foundation connected to the following one by a bridge. A chronicler noted in 1285 that "the square facing the lagoon was enlarged by Doge Dandolo, which previously had not been there except for a small foundation, where there was a bridge."[25]

Enrico Dandolo, Pietro Ziani, Jacopo Tiepolo[edit]

After Orio Mastropiero came to the throne, Enrico Dandolo had promised as a vow the erection of a chapel in honor of St. Nicholas, so that the latter would protect him in his war against the Turks.[26] The chapel was built under the dogate of Pietro Ziani in an area overlooking the Palace canal that had been specially enlarged, and was then moved, in the 16th century, to the doge's apartment:[22] it was long thought that the chapel had been erected at the latter's behest but, considering that the walls, decorated by means of a bequest from the Coppo family,[22] depict the conquest of Constantinople, it is more likely to be the late fulfillment of the previous doge's vow.[26] Ziani's political heir was Jacopo Tiepolo, who, according to the sixteenth-century religious scholar Gerolamo de Bardi, commissioned a decoration of the Hall of the Great Council that included a depiction of the life of Pope Alexander III.[27] The existence of this decoration was in the past cast into doubt because of the lack of knowledge of the place where this organ gathered from the time of Ziani until 1423, when it was supposedly transferred: today it is possible to state that, in accordance with the assumptions of nineteenth-century sources,[27] the primitive hall of the Great Council was located in the southern wing, on the first floor.[1] In this case, however, it is impossible that the decorations of the time had been preserved until Bardi's time since this hall was completely renovated following a decree of 1340.[27][28] Instead, it is more likely that the paintings observed by Bardi were those made in 1365 by Pisanello during the decoration of the new Hall of the Great Council, works that were lost during a subsequent fire.[29] During Tiepolo's dogate, a fire occurred (either in 1230 or 1231) but, contrary to what is attested by some period sources, the Doge's Palace was not damaged.[29]

Reniero Zeno, Lorenzo Tiepolo, Giovanni Dandolo[edit]

Until 1301 there is no record in any chronicle of whether the Doge's Palace underwent any other work, but this does not mean that no building site was operating there during that time.[30] In 1232 Frederick II of Swabia was probably housed there.[31]

Under the dogeship of Reniero Zeno the square was paved.[32] It is also said that just after his appointment as doge Lorenzo Tiepolo remained on the landing of the main staircase of the palace, located where the Scala dei Giganti is today and in front of what was the main entrance to the palace, to listen to the praise he was being given: this practice, perhaps predating Tiepolo, was maintained with some variation later on.[33]

Under Giovanni Dandolo a loggia was erected, which, despite some evidence that would place it near the church of San Basso, was probably located at the foot of the bell tower in the place now occupied by the Loggetta del Sansovino.[33] The fact that this loggia was probably in line with the main door of the palace and with the staircase mentioned earlier suggests that the ancient entrance was located where the Porta della Carta was later erected. Also during Dandolo's dogate, the part of the small square facing the lagoon was also enlarged.[34]

The Great Council in the Senate Hall[edit]

After Francesco Dandolo came to the throne Pietro Gradenigo, the author of a series of laws better known by the name of Great Council Lockout, an operation aimed at allowing access to the Great Council only to those who had been able to prove that their ancestors had already been members.[35] Given this definition, and analyzed what the purpose of this law was, the name lockout does not correspond to a reduction in the number of those who were admitted to the council itself. Rather, there was an increase in the number of councilors,[36] which necessitated an expansion of the premises intended to house the council itself,[37] whose membership had increased from 317 in 1264 to 900 in 1310 and to 1017 the following year. The proposals that were most successful among those that were made to enable all the members of the council to meet in the same room were that of also using adjoining rooms, without incorporating them, and that, later brought to fruition, of radically remodeling the premises, incorporating smaller rooms, building load-bearing walls, and tearing down others.[37] Some chronicles[38] report that in 1301, the year in which the discussion of this issue was resumed, defining the rules of the proclamation, the date of the start of the work, and the penalties for those who slowed down the progress of the work,[37] "it was decided to make a Great Hall for the reduction of the Great Council, and what is now called the Scrutiny Hall was made": the work, according to Francesco Sansovino, was completed in 1309, and the Great Council continued to meet in that room, later called the Hall of the Pregadi, until 1423.[35][39] The rooms housing the services and organs related to the Great Council were also moved to a place adjoining the new space. From the simple renovation of one room, it became a more complex building site, which was to include the reconstruction of the entire southern wing: this was due not only to the new practical needs, but also because the Great Council was becoming increasingly important, to the detriment of the figure of the doge, and therefore its hall was to demonstrate the influence and wealth of the members of that body.[37]

However, the dating of this building site cannot be given very precisely (although roughly the period is fairly certain), as other sources, and in particular the works of Marin Sanudo the Younger, sometimes give 1305 as the date, other times 1310.[21] It is not known who was responsible for this work, just as it is not certain where the council met before it (although there are well-founded hypotheses that before the Serrata the council met in the same place as where it would meet after 1423, after said room was duly enlarged.)[21][22] nor what the decorative apparatus of the room housing the council was.

Pietro Basejo, mentioned in a document of 1361 but who died in 1354, is one of the alleged authors of the renovation work.[21][40] Since biographical information regarding Basejo is rather scarce, it cannot be attested what age he was in 1301 since his date of birth is unknown.[41] Another line of research has identified as the possible author of these renovation works the architect Montagnana, mentioned by Sansovino[42] as the author of the renovation of the bell tower and according to Tommaso Temanza potentially also the chief architect of the Doge's Palace,[41][43] that is, the first architect of the Republic, in charge of directing all major public building sites and in particular that of St. Mark's basilica.[44] Hints as to what the decoration of the room was are provided by Sanudo in his diaries: on June 5, 1525 he states that there were panels depicting large and small trees, with an allegorical function. However, it is probable that there were also cartographic depictions of the Serenissima's possessions and a Coronation of the Virgin at the throne.[45] In 1525, the year in which the reconstruction of the hall was deliberated, Sanudo complained that such a valuable room could not be destroyed on pain of losing the masterpieces contained within.

Construction sites in the southern wing[edit]

The hall went into operation in 1309, and became the de facto second seat of the Great Council, but it soon became necessary to change the seat of the housed organ because of the one-third increase in the number of those who were allowed to join it between 1301, the year in which work for Sansovino began, and 1309, the year in which it was completed.[45][46] The need to find new space for such a large body made it necessary to open building sites in the southern wing of the palace, dated by Sansovino to 1309.[47] Concerning the building of this new wing, the contrast between the different sources has been presented, which, by stating different data, make it difficult to reconstruct the chronology related to this work. The construction site was opened simply because of the need to build the Hall of the Great Council and not for any other purpose.

There are several elements that support the thesis that the construction of the new hall began immediately after the conclusion of the previous works: first, the pressing need to find a new site for the Great Council; second, the accuracy of the historical sources used by Sansovino, very often written by contemporaries of the works dealt with and thus able to record the data with extreme meticulousness; and, finally, the presence of a document found by the abbot and historian Giuseppe Cadorin, in which it is stated that in 1340, the year identified by many as that of the construction of the hall, the hall had already been erected as had the wing that housed it and thus needed not so much to be built, housing various administrative bodies.[48] The new hall was erected over the pre-existing Hall of the Lords of the Night, which it traced in width; moreover, a number of columns were built in the said hall to support the floor of the room above, according to the advice of some expert masters. Work then began in 1309, consisting of the demolition and reconstruction from the foundations of the southern side facing the sea, a wing where the Great Council had already previously met, later temporarily relocated to the Hall of the Senate or Pregadi. The decree of December 28, 1340, which ordered the construction on the second floor of the said area of the new hall dedicated to the Great Council, bears witness to the fact that at that time the second floor was already being used for other offices.[49] The reconstruction work was strongly promoted by Doge Giovanni Soranzo, who was also able to carry out other works that promoted the urban development of the Serenissima, which was also accompanied in parallel by the building of numerous private residences. The fact that the realization of such works was carried out under the aforementioned doge is evidenced by the presence of an official document, concerning the financing of public works, from which it can be deduced that in 1323 the construction of the wing had reached the second floor and that the newly built halls were being covered in some areas and the ceilings were being repaired in others.[50]

Regarding who was the architect in charge of this building site, which was started in 1309, ref=Egnazio|Giovanni Battista Egnazio identifies him as Filippo Calendario.[51] However, this reconstruction must be compared with a document dated September 23, 1361, reported verbatim in Cadorin's chronicles and constituting one of the main biographical sources regarding Pietro Basejo, identified therein as the first architect at a time before Calendario's activity.[52]

Consequently, it can be said that the building of the wing facing the sea up to the second floor was Basejo's work,[50] although Calendario's name, in any case not unrelated to the building site, was not lost like the other's in the oblivion of time by virtue of the fact that the latter had great prestige among the people and was among the conspirators in the coup d'état hatched by Marino Faliero in 1355.[53] Calendario's participation in the construction site is, however, highly probable, but his intervention probably took place later and always in parallel with the activity of the former, with whom he would later enter into such a friendly relationship that he would give his own daughter Caterina in marriage to his colleague's son.[53]

Other works between 1309 and 1340[edit]

At the same time as these works, in 1322 the church of San Nicolò, located in the wing facing the canal, was enlarged to the detriment of the adjacent rooms, enriched with marble columns of oriental workmanship, and decorated with the stories of Alexander III, which was finally provided with an apse and windows in the Gothic style typical of the period.[22][53] Although the author of this decoration is not known, Cadorin proposes two hypotheses: according to his reconstructions, the maker could be either Guariento di Arpo, or an unspecified master Paolo, who was active in 1346 and who was the author of an altarpiece for the same chapel.[54] The work of this painter is attested by chronicles of the time,[53] while Guariento must have been very young at the time.

At the same time, a cage was also made under the portico of the Doge's Palace, suitable for housing a pair of lions, which gave as offspring three cubs, one male and two females, one of which was sent to Verona as a gift to Cangrande della Scala.[53] This cage proves the existence in the courtyard of a loggia on the ground floor of the western wing, erected under the dogate of Pietro Ziani. That loggia would disappear during the works carried out in that wing starting in 1424.[55]

At the end of the year 1326, the seat of the prisons located on the ground floor was enlarged, necessitating the relocation of the seat of the palace's gastalds. Given what their seat was, it can be said that before then the palace prisons had occupied only the southern side of the palace and part of the eastern side.[55]

In 1332 a new building site targeted the palace wells: the most important one, located in the center of the courtyard, was repaired, and a smaller one was built in a small courtyard bordering the basilica.[56] A third well was added in 1405.

In 1335 stonemasons were contacted for the creation of a marble lion to be placed above the main entrance to the palace, corresponding to the main staircase. The gilding of that work dates back to 1344, as attested by an official document that also gives some important information regarding its placement:[56]

—November 4, 1344

This information makes it possible to state that the ancient inner door and the ancient staircase in front of it were nothing more than the ancestors of the present structures (the door connected the small square with the courtyard and was located on the straight line joining the Loggetta del Sansovino and the ancient staircase, located where the Giants' Staircase is today; however, these works were replaced by more modern structures a few years later). In the reconstruction of the internal elevation of the eastern body the prefixed scheme was respected, and in particular that the Giants' Staircase corresponded to the ancient staircase, as did the Porta della Carta to the ancient arch.[56] This lion would have been more precisely placed on the door of the staircase that joined the eastern side of the then functioning Hall of the Great Council to the courtyard, a staircase commissioned in 1340 and finished four years later.

The expansion of 1340[edit]

Having already redeveloped the second floor of the southern wing in its entirety, in 1340 a series of other works were decreed to be carried out in the palace, not consisting in actual building but, if anything, in expansion. These works consisted of building or rearranging the second floor, completing the Hall of the Great Council (this body continued to meet in the Senate Hall until 1423), renovating for the new purposes for which they were intended some of the rooms adjacent to what would have been the Great Council, and erecting a staircase communicating with the Great Council Hall: the cost budgeted for their realization was 950 lire for the architectural work and 200 lire for the decorations, which adds another valid support to the thesis that does not see this work as a rebuilding, but only as an enlargement consisting of the arrangement of the second floor, since if it had been necessary to provide for the reconstruction the expenses would have been much greater.[57][58]

Fifteen months after the opening of this building site, it was decreed that more work was needed, as the hall was to become larger than planned: the fact that on March 10, 1342, the floors below the Hall of the Great Council had already been completed testifies that the reconstruction work had not begun again in December 1340 (the year of the aforementioned decree), but already in 1309, as testified by Sansovino.[57] With the part of the hall facing the lagoon completed at the end of 1344, ten surveyors were called under a decree of December 30, 1344, to examine whether the walls facing the courtyard were suitable to support the weight of the wall that would enclose the hall on that side:[57]

—December 30, 1344

The ground-floor wall, which surrounded the prisons, supported only the loggia of the second floor and it was not known whether it would withstand further pressure. This element, too, contributes to the idea that the building of the first and second floors took place at different times.[57] Having received a positive opinion from the surveyors, the building of the staircase and its door began. Work was interrupted because of the Plague that broke out in 1348, and resumed on February 24, 1350.[59]

It is known that Filippo Calendario tajapiera and Pietro Basejo magister prothus were employed as directors of the work, as well as a very large number of laborers, sculptors, and expert stonemasons.[60] The director of the work was initially Basejo, upon whose death Calendario took over.[61] The former's activity is suggested by the fact that around 1350 Calendario was commissioned to make a series of trips on behalf of the Serenissima, and also during that period he engaged in a number of military campaigns: this testifies that he did not have a fixed commitment to the construction site.[61] Calendario in 1355 was sentenced to death by hanging as the plotter of the conspiracy promoted by Doge Marino Faliero. It is handed down that his sentence was carried out in conjunction with that of his son-in-law and using the famous red columns of the palace balcony, the location of which was altered over time.[61] As the conspiracy saw extensive participation among the stonemasons of the Doge's Palace, the work remained suspended.[62] The worksite remained on hold for various lengths of time due to war events and a second plague.[62] By 1362 the palace was in ruins. Because of Lorenzo Celsi's willingness to finish the work, it could be said to have been completed in 1365. However, Celsi, hated for his arrogant behavior, died mysteriously and was speculated to have been poisoned. After his death, it was decreed that "the doge could not in the future employ public money in the expenditure of works in the palace, without the consent of the six councillors, three-fourths of the Quarantia and two-thirds of the Great Council."[62] The Doge's Palace, after all these works, did not present a very different appearance from its contemporary one.[60]

When Marco Corner ascended the throne, he ordered the Great Council Hall to be decorated with paintings: one of the artists contacted was Guariento di Arpo, who was commissioned to decorate the eastern wall of the hall with the theme of Paradise, and more precisely of the coronation of the Virgin amidst the glory of it.[63] Later the same artist devoted himself to the decoration of the other walls, illustrating there the coming of Alexander III to Venice and the War of Spoleto, as some sources recall.[46][64] Pisanello also worked on this site, according to Scipione Maffei's reconstructions.[65] Sansovino asserted that the painting, depicting Emperor Otto going to his father after being freed by the Serenissima, included a portrait of Andrea Vendramin, said by many to be the most handsome Venetian young man of his time: in asserting this, the great historian made a mistake since Vendramin had not even been born at that time; another mistake made by Sansovino was to assert that the room had already been previously decorated.[63]

Among others, it can be assumed that Nicolò Semitecolo and Lorenzo Veneziano also took part in the decorative work.[63] During this decorative work, the frieze depicting the faces of the doges was created for the first time, starting with Obelerio, which was later reproduced after it was destroyed by fire in 1577. Sanudo states that the inscriptions illustrating the pictorial works were produced by Francesco Petrarca, which is not impossible.[63][66] Later, however, after a period of continuous wars (1368-1381), Venice found itself in difficult political and economic conditions, and therefore the decoration works (which by then were drawing to a close) were interrupted.[67]

After it had been decided to repaint the palatine chapel whose decorations were in ruins,[68] it was Michele Steno who favored the completion of the decorative work in the hall.[67] The ceiling was made of coffers decorated with stars, possibly alluding to the doge's coat of arms.[69] Sanudo states that this work remained unfinished for a long time and was only completed in 1406.[70]

A large balcony was also built in those years in the central part of the facade facing the sea, in 1404 according to reports on it, in the following year according to Sansovino.[67][69] Regardless of whichever of the two dates is taken as true, it is in any case erroneous what Tommaso Temanza claimed in attributing the decoration of this work to Calendario, since the sculptor had already been dead for half a century (in 1355).[67][71] Another mistake was made by Pietro Selvatico, who dates the entire southern front to 1424, making it contemporary with the one erected under Francesco Foscari.[67][72]

This error was due to a misinterpretation of what was written in the Cronaca Zancarola, and was pointed out by Dall'Acqua, who understood its causes and justified it by saying that the chronicler in writing what he had reported spoke in the plural of facades of the western side referring to the outer and the inner one.[73] It should also be noted that the very date given on the window (1404) is indicative of the fact that this facade at the time must have already been built and that there are substantial differences in the style of the two fronts.[74]

The renovation of 1424[edit]

After the aforementioned renovations and as a result of the many wars fought by the Serenissima, the coffers of the state were in a very bad condition,[75] and it was therefore resolved that the facade facing the Piazzetta should no longer be renovated, under penalty of a fine.[76] Between 1404 and 1422 this promulgation was respected, and apart from minor renovations (enlargement of the office of the Old Auditors[77] and construction of a stone staircase connected to the Hall of the Great Council)[78] no other work was done. However, Tommaso Mocenigo proposed to renovate the bound facade, risking a fine of 1,000 ducats, but managing to convince the Great Council by arguing that such renovation was necessary for the decorum of the city, since that wing was very old.[76] After the doge had paid the fine, it was decided in the Great Council on September 27, 1422 to renovate the oldest wing.[79]

Some sources speculated that this renovation work had been made necessary because of a fire that broke out on March 7, 1419, and that the entire palace had been affected according to a plan approved by the doge himself,[80][81] but this is false since the fire had only caused damage to the Basilica without damaging the palace,[82] and the already existing wing had been taken as a model for the one to be built.[80] For a number of reasons, including a plague that broke out in 1423, the work could not start until 1424.[83] The first meeting of the Great Council in its new seat took place on April 23, 1423,[84] according to a resolution of the newly elected doge Francesco Foscari. The old seat was left to the Senate (which had previously met in the wing toward the Piazzetta),[39] and thus took the name Hall of the Pregadi, as the senators were requested by the doge to accept their function.[85] The demolition of the wing toward the Piazzetta took place on March 27, 1424.[86][87]

The authors of the renovation were some members of the Bon family - Bartolomeo, Pantaleone, and Giovanni. After work had been done on the reconstruction of the demolished wing until November 1438, it was decided to erect within eighteen months the door that would be the main entrance to the palace through an agreement, made on November 10, between architects and superintendents.[60][88] However, the timetable set for the work was not respected, and the construction site, which began on January 9, 1439, was completed in forty months,[89] after various solicitations from the officials in charge,[88] and after a second agreement had been made in which the sculptors undertook to complete the work by 1442 under penalty of a fine of ten ducats, which was also not fully complied with.[90] It can be deduced from the presence of Bartolomeo's name alone on the architrave that the high relief above the door is the work of him alone, but this does not mean that the other members of the family did not participate in the worksite,[90] contrary to Cadorin's claim. The gate, which changed its name several times over the ages, was known as the Porta della Carta: the origin of this may be due to several legends: the first states that there were large stores of paper near it for the neighboring offices, the second that many documents passed through it,[90] the third that public scribes crowded around it.[91]

The new building had a portico on the ground floor, uncovered loggias on the first, and on the level of the Great Council Chamber a large hall known at the time as the Library Hall, later changed to the Scrutiny Hall.[60] The elevation of this new building body was completed with decorations very similar to those on the façade on the pier: it has a pinnacled crowning and large windows.

Building sites after 1441[edit]

Although Cadorin claimed that in 1441 all the renovations could be said to have been completed,[92] as Francesco Bussone was welcomed into the palace (but he was mistaken in that the count was given access from the part of the palace facing the sea),[93] the building site could not be said to have been closed in 1452, as Frederick III of Habsburg was hosted in the palace and for this occasion stones were removed from St. Mark's Square that were used for the building site of the Doge's Palace.[94] On May 30 a party was held in honor of the emperor,[94] but the record of receptions in that hall belongs to that for the wedding of Jacopo Foscari, son of the doge.[95]

According to Sanudo, Pasquale Malipiero gave orders to build the arch in front of the Giants' Staircase, where he would have his own coat of arms placed,[96] but this information is incorrect since the coat of arms is of Doge Foscari and that arch was erected in another year.[97] The works that were carried out during Malipiero's dogate were others: the outer front towards the Piazzetta was completed (this is evidenced by the hanging of Girolamo Valaresso through the use of red columns)[98] and orders were given for pictorial works such as the one narrating the defeat of Pepin on the Orphan Canal and the one depicting a globe.[99][100] Authors of these works could have been Antonio or Luigi Vivarini.[99]

Under the dogate of Cristoforo Moro, on September 6, 1463, a document was promulgated concerning the construction of the arch facing the Giants' Staircase, or Arco Foscari. Once again, an agreement was made with Pantaleone and Bartolomeo Bon for the completion of this work, for the delay of which the fine would have been two hundred ducats, but no trace remains of solicitation by state administrators, and it can be said that this work was completed under the dogate of Moro, the latter's coat of arms being four times represented on the work.[99] The room that would later be known as the Scrutiny Hall was designated from 1468 by decree of the Senate to house the volumes donated to the state by Cardinal Bessarion.[99] In 1471, when Nicolò Tron ascended the throne, a feast was set up in that room to celebrate the entry into the palace of Dea Morosini, the doge's wife.[101] In 1473 it was decreed that some of the works in the Great Council Hall should be replaced, as they had been ruined by infiltration. Giovanni and Gentile Bellini were called in to redo the work depicting the battle against Frederick Barbarossa.[102] Luigi Vivarini, Cristoforo da Parma, Lattanzio da Rimini, Vincenzo da Treviso, Marco Marziale, and Francesco Bissolo were also engaged in those renovation works, which lasted until 1495;[102] Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese would also be called in to work in the room at a later date.[102]

The three fires[edit]

The fire of 1483[edit]

On the night of September 14, 1483 (but according to other sources in the year 1479)[103] a disastrous fire broke out in the rooms facing the Rio di Palazzo, and more precisely in the Palatine Chapel, destroying the adjacent rooms and various works of art.[104] Domenico Malipiero, a chronicler, testified that the aforementioned fire broke out when a candle set fire to a painted panel located near the altar on which it was placed, which in turn caught fire.[105] After some people living on the other side of the canal warned Doge Giovanni Mocenigo, he too found refuge on the other bank. The doge's seat was moved to a private house belonging to the Duodo family, which was put in communication with the doge's palace.

After the great fire, reconstruction work became necessary, for which it was initially planned to allocate only 6,000 ducats, and only later 500 ducats per month.[103][106] Nicolò Trevisan, from whose house the fire had been glimpsed, proposed the purchase of many houses overlooking the Rio di Palazzo in order to build on those lots a palace with a garden that would then be connected to the College Hall with a stone bridge, but this proposal was rejected and the work was entrusted to the architect Antonio Rizzo, who was salaried 100 ducats a year (although at a later stage his salary increased to 125 ducats).[106][107] As soon as Rizzo took charge of the work, the sections of the palace that would later be rebuilt were demolished and a number of employees were commissioned to provide the stones needed for the construction, which were delivered on December 8, 1484. Rizzo's collaborators for this construction site were, according to Giuseppe Cadorin, Michele Bertucci, Giovanni da Spalatro, Michele Naranza, Alvise Bianco, Alvise Pantaleone, mastro Domenico, Stefano Tagliapietra, and the Lombardo family.[108]

After demolishing the part of the eastern wing included between the basilica and the present Golden Staircase, Rizzo had the first pillars of the portico erected, the dating of which is possible because a portrait of Doge Mocenigo appears in the capital of the first and third, and the coat of arms of Marco Barbarigo in the other. Under Agostino Barbarigo the Giants' Staircase was built ex novo,[60] while of some rooms, including the Senate Hall, was preserved as much as could be of the old structures.[109] The new structural layout gave Rizzo the opportunity to build the various floors by constructing their pavements at the same height as those of the noble floors of the southern and western wings.[109] Some authors, including Sansovino, identified the facade facing the inner courtyard, which shows in the loggias the emergence of Renaissance taste, as the work of Antonio Bregno, but this is an error.[109] Rizzo continued to work exclusively in the building being paid 125 ducats until October 1491, when he requested that his salary be further increased.[109] The Senate ordered that the Salt Superintendents come to an agreement with the artist, and an agreement was reached that the latter would be paid 200 ducats annually.[110] On March 19, 1492, the doge was able to return to his rooms, from which it can be deduced that they were at that time completed.[110]

After a brief interruption due to some major expenses of the Serenissima, on September 11, 1493, the Council of Ten ordered that the work be resumed.[111] Rizzo remained engaged in the building until 1498, when Francesco Foscari and Girolamo Cappello, superintendents in charge of the work, discovered that out of the ninety-seven thousand ducats hitherto spent ten thousand had been improperly misappropriated by the architect, who fled to Ancona.[110] Another stone-cutter, Simone Fasan, was also accused of embezzling public money.[112]

Francesco Foscari and Hironimo Capelo, deputies of the Lordship, found that Master Antonio Rizzo, who had been working on the palace for 15 years with a budget of 200 ducats a year, had taken more than 10,000 ducats from what had been spent so far on the construction of the Prince's palace, i.e. 97,000 ducats. [...] Master Simon Faxan and others who worked with him also committed a major theft.

— Sanudo, Diarii, I, p. 27, 5 April 1498

The works were entrusted ad interim to Pietro Lombardo, who was confirmed on 14 March 1499 and paid 220 ducats a year from the 16th of the month[113] until 1510.[114] He took control of the building site, but it had already progressed quite a lot, since the decorations on the second floor bear the coat of arms of Agostino Barbarigo, who had died only three years and five months after Lombardo had taken over.[112] In 1503 lead was provided for the roof covering.[111] The façade on the Senators' Courtyard was then made, which was started at the same time as the main façade and completed under Leonardo Loredan, as shields of the latter and of the Mocenigo were found in the decoration of that façade and there was a capital joining the two fronts.[115] Cicognara therefore made a mistake in saying that the façade on the courtyard was entirely the work of Guglielmo Bergamasco under Loredan,[116] as there are coats of arms of the previous doge and the style is the same as that of the main one, by Rizzo.[114] Some details can also be attributed to the style of the Lombardo family,[117] and the participation of Giorgio Spavento cannot be excluded.[118]

Between the completion of the work on the facades and the death of Doge Loredan (21 June 1521) few other works were completed due to the difficult economic situation of the government, which was fighting against the League of Cambrai between 1509 and 1517.[119] Firstly, fireplaces were made in the ducal residence; around 1505 the frames of some canvases were gilded;[120] from 1507 onwards Spavento worked in the Audience Hall and in the chancellery;[121] in 1509 the watchtower was renovated by Bartolomeo Bon (namesake of the same Bartolomeo Bon who worked on the construction of the Porta della Carta);[122] between 1509 and 1510 Pietro Lombardo worked in the Hall of the Council of Ten and in that of the Avogaria del Comune;[119] in 1515 a lion was placed on a staircase that was later demolished[123] and the painters responsible for the decoration of the Hall of the Great Council were solicited and a new agreement with Titian was made.[124]

At the same time as the façades on the courtyard were being erected, work was also being done on the one on the canal, and this is testified by the presence of the coats of arms of Giovanni Mocenigo, Marco Barbarigo and Agostino Barbarigo on it.[125] At Loredan's death, the part up to the first entrance of the vestibule on the ground floor, corresponding to the point where the height of the rooms on the third floor varies, was completed.[125] After Antonio Grimani's brief dogate, work continued on the building, but at a slower pace since other important construction sites were also open (Rialto Bridge, Venetian Arsenal, Zecca of Venice, Marciana Library). Antonio Grimani was the first doge to make use of the now completed Giants' Staircase to visit the Basilica with his lady on 14 July 1521.[126] Under Andrea Gritti, since the interiors of the palace had not undergone structural renovations, a wall in the Hall of the Pregadi threatened to collapse: the doge immediately went there with Antonio Abbondi, chief architect of the palace,[127] and other experts, who decreed the need to intervene.[128] The damage was due to infiltration.[129] It was thought to move the Senate to the Scrutiny Hall, used as the Library,[130] but this proposal did not prove suitable.[131] However, the work remained at a standstill for two years, although the benches occupying the room were moved.[132] The work was completed by the Doge and the Senate.

In the meantime, as the decoration of the chapel of San Nicolò was completed by Titian[133] in 1523, it was decided to demolish the small palatine chapel located in the southern area,[22] to be renovated:[134] on 15 February 1524 the offices of the Avogadori di Comun were moved as they were located nearby.[135] In 1525, the Council of Ten decreed to begin work on the Hall of the Pregadi, which had been at a standstill since 1523, and to build a corridor by which the Senators and the Doge could access the Hall of the Great Council:[136] the building site was opened in October[137] and the Senate found a new location in what is now known as the Hall of the Antechamber, which was once called the Golden Hall.[138]

In the meantime, work proceeded on the reconstruction of the façades of the eastern wing, all the offices located there were removed,[139][140] the prisons from which the prisoners had twice managed to escape were repaired[141][142] and two staircases were used to move around the palace, one leading into the Audience Hall[143] and the other into the Great Council Hall.[144] On 26 April 1531 it was decided, after some disagreements by the Council of Ten, to divide the Library Hall into two rooms, one for the ducal chancellery and the other for the scrutiny room of the Great Council.[145] The historical collection of books located there was then moved to the Marciana Library[146] and the two doors connecting the Scrutiny Room and the Great Council Hall were enlarged.[147][148]

A large clock was then built by Raffaele Penzono on the wall between the Hall of the Antechamber and that of the Senate:[149] Today there is another one, built after 1574, which is located between the Senate and the College, also on the same wall.[150] As the work in the eastern wing had not been completed, it was necessary for the Council of Ten to deliberate again and allocate 400 ducats a month for that work,[151] but this also had no effect due to the fact that the construction of the Scrutiny Hall was already in progress[152][153] (a hall used only in 1532[154] and completed later[155]): it was the Senate that would return to this matter a year later. On 28 May 1532 it was resolved to demolish the ancient small tower, which was then no longer rebuilt,[156] at that time still in use but already damaged by fire a few months earlier.[157]

In view of the fact that operating off-site caused various inconveniences to the various offices,[158][159][160] on March 27, 1533 discussion resumed in the Senate concerning the previous proposal of the Council of Ten to complete the work of rebuilding,[161] which in 1538, however, had not seen progress. During the dogate of Pietro Lando only the decoration of the state rooms was continued: Titian,[162] Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto worked during this period.[163]

Only under Francesco Donà, aided by the peace and prosperity that came with his dogate, did the building site receive a decisive turnaround, under the direction of Antonio Abbondi.[164] The building site of the eastern wing was not finally completed until September 1550.[164] Shortly after the end of the work, but before the conclusion of Donà's duchy, the two balconies of the Hall of the Great Council were made, which, facing the inner court, allowed for its ventilation: this work was not completed until 1554.[165]

Later, up to 1574, various works of mere decoration were carried out in the palace by Il Pordenone, Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Alessandro Vittoria, Jacopo Sansovino and Battista Franco in the new wing, the Golden Staircase, the Scrutiny Room, and the Great Council Chamber,[165] but many of these would be destroyed in the two subsequent fires. The last act of reconstruction took place in 1566: it was the installation at the top of the Giants' Staircase of two famous statues by Jacopo Sansovino, depicting Mars and Neptune.[166]

The fire of 1574[edit]

On May 11, 1574, due to the carelessness with which the fire was guarded during the celebration of the anniversary of Alvise Mocenigo's rise to power, a great fire broke out in the ducal apartments:[167] the doge and senators were saved, but the fire broke out in the halls of the Pregadi and College, the Antechamber and the Four Doors, destroying, among other things, paintings by Titian and other decorations in the rooms.[168] Fortunately, some palace employees, lawyers, and ordinary citizens removed some very important papers from the rooms near the fire, preventing it from damaging the hall of the Heads of the Council of Ten and that of the Great Council; however, due to a strong wind, the fire spread to some of the domes of St. Mark's Basilica and the Baptistery,[citation needed] which Francesco Molino and ref=Sansovino|Sansovino claim were not damaged in any way by the fire.[169][170] Some sources believe that the flames even reached the notches near the bells of the bell tower of the basilica, but this thesis is refuted by others, including Zanotto, who argues that it was impossible for the fire to reach that height.[168]

A number of naval soldiers rushed to extinguish the fire, who the following day refused the reward of five hundred ducats offered to them by the Senate, and all the magistrates of Venice, who in addition to extinguishing the fire worked to maintain order in the city, which was agitated by the news of the fire.[171] The doge moved to live with his brother Giovanni, in Palazzo Mocenigo.[171]

Once the flames were extinguished, the senators elected three men to take care of the reconstruction of the damaged rooms: Andrea Badoer,[citation needed] Vincenzo Morosini and Pietro Foscari, who appointed Antonio da Ponte as director of works.[171] Also working with da Ponte were Cristoforo Sorte, who took care of the hall of the Pregadi, Andrea Palladio, who decorated the hall of the Four Doors, and Vincenzo Scamozzi, who took care of the hall of the Antechamber.[171][172]

The work saw the display of great luxury that demonstrated the wealth of the Venetian Republic, through the use of precious marbles, capitals, paintings and sculptures with no expense spared.[173][174] The reconstruction of the rooms continued even after the fire that occurred three years later, and at the turn of the 1670s and 1680s some documents attest that work was still being done on the Pregadi room. Observation of the paintings in the new rooms also shows that doges who ruled from 1577 to 1605 are depicted there, which shows that the work was not completed until the 17th century; these delays were probably due to the plague epidemic that decimated some 51,000 inhabitants in Venice from 1575 to 1577.[174][175]

The fire of 1577[edit]

On December 20, 1577 (although many writers state, erroneously, that it was January 13, 1578) a new fire broke out at the Hall of the Scrutiny, in the vicinity of the Porta della Carta, due to the lighting of a vigorous fire by the palace guards in a chimney containing old soot, which gave rise to the flames.[176] The roof of the room, made of lead sheets, began to drip from the heat of the fire, preventing access to it and other nearby rooms and the removal of the works of art placed there. Sansovino, at this point, erroneously claims that the roof was made of copper,[177] while both Cerimoniale and Molino state that the copper roofing was not done until after the fire of 1577.[178] Despite the rush of workers to contain the fire, the ceilings of the halls of the Scrutiny and the Great Council collapsed, destroying valuable works of art by Carpaccio, Bellini, Titian, Tintoretto, and others.[176]

The fire was isolated with great effort by the Arsenal workers, who, lowering themselves with ropes, managed to extinguish it against a load-bearing wall: the operation was concluded around the third[169] or sixth hour[179] It was feared that the fire had been set by enemies of the Republic, so many senators kept armed vigil in St. Mark's Square all night.[179]

For safety, the weapons contained in the Hall of Ten were transported to St. Mark's Basilica, while the documents of the archives were placed in the residence of the Grand Chancellor, in the sacristy of the basilica, in the ducal rooms, and in the loggia under the Bell Tower; however, many valuable objects and important papers were lost.[180]

Doge Sebastiano Venier remained in his apartments, showing great courage, while Senator Luigi Michiel protected the Library and the Mint from the flames by wetting their roofs.[180] The following day, the Arsenal workers refused the compensation awarded to them by the Senate for saving the palace, just as they had done in 1574.[180]

Since the hall of the Great Council was unusable, the Senate took to gathering in the circuit of St. Mark's basilica, after considering other places;[181] the architects, including da Ponte and Palladio, ruled that three months were needed to accommodate it as the seat of the Great Council: during that time the Senate gathered inside the basilica.[181][182]

However, due to the impediments constituted by the celebrations for Lent, the Council moved to the two halls of the Remi, in the Arsenal;[181] new entrances were built that would allow the nobles to access them without passing through the building site.[181] On January 18, 1578, Luigi Zorzi, Jacopo Foscarini and Pietro Foscari were elected as procurators for the reconstruction of the damaged halls of the Doge's Palace.[181]

Fifteen architects were called upon to rebuild the palace: Giovanni Antonio Rusconi, skilled in hydraulics; Guglielmo de Grandi, an expert on the Venetian lagoon; Paolo da Ponte; Andrea da Valle; Andrea Palladio,[172] who was already in charge of the Hall of the Four Doors; Angelo Marcò; Francesco Sansovino; and Francesco Malacreda, an important military architect; Jacopo Bozzetto, architectural expert; Jacopo Guberni, attaché to the magistrate of Waters; Simone Sorella; Antonio Paliari, skilled in the art of masonry; Francesco Zamberlan, famous architect, mechanic and inventor; Cristoforo Sorte, engineer, architect, choreographer and writer; Antonio da Ponte, chief architect of the palace.[183][184]

The architects were asked what state the walls of the palace were in, whether these could support a new roof or whether the cracks undermined its stability and if so what fixes could be made; whether the remaining beams and capitals could be kept, whether the walls needed strengthening, whether the palace could be considered stable, and how long it would take to repair the damaged areas; what precautions needed to be observed if the prisons were to be removed from the ground floor of the palace.[185]

The architects' answers to these questions were mixed; for a long time it was mistakenly believed that Palladio wanted to raze the entire palace to the ground and rebuild it according to his own design.[185] Sansovino, as well as Rusconi, Paliari, and Sorella, were firmly convinced not to touch the original structure of the palace, which was considered very solid.[186] In favor of minor structural changes were Malacreda, Guberni, Bozzetto, Marcò, and Zamberlan, who would have liked to add pillars and vaults.[186] Da Ponte and dalla Valle, on the other hand, were strongly opposed to the palace, judging it unsafe because of its construction.[186] Sorte was also skeptical of the corner toward the Ponte della Paglia bridge, which he considered unsafe;[187] de Grandi envisioned a facade adorned with several orders of columns of different styles.[183][187]

Contrary to popular opinion, Palladio and da Ponte did not dispute the design for the palace at all; on the contrary, they agreed to keep the original structure, applying only minor modifications including the insertion of pillars to strengthen the damaged walls.[187][188] The renovation was to last four years, and it was to include the construction of fourteen vaults for each of the two facades, the replacement of ruined stones and the laying of a new truss, the repair of the walls damaged by fire, the placement of chains to support the wall toward the Ponte della Paglia, and the replacement of the cracked capitals.[188] Da Ponte's design was chosen as the least invasive among those proposed by the other architects, and on February 21, 1578, he began work assisted by the others.[188]

The architect's first undertaking was to remove the ruins from the halls of the Scrutiny and the Great Council, which were then sold for the price of four hundred ducats.[189] Later he became interested in the difficult structural question concerning the corner near the Ponte della Paglia, where the walls were unbalanced toward the canal.[190] Of the series of arches in front of the prisons, the first two and the fifth were walled up, and the prisons placed there were converted into offices. Then the architect replaced the damaged trusses and repaired the capitals of the loggia, instead of replacing them, by girdling them with iron hoops;[190] then he covered with a new roof formed of larch beams the hall of the Scrutiny and that of the Great Council, taking only two months.[190] The roofs were covered with sheets of copper, and not of lead, as the latter melted, and thus caused more damage.[191] Next came the restoration of the interior, the windows (which he deprived of the triforas to provide more light inside),[191] the walls and the floor, so quickly that the Great Council Chamber was ready for use as early as September 30, 1578.[191] On that occasion the new hall hosted a procession.[192]

The project of decorating the ceilings of the halls of the Council and the Scrutiny were respectively assigned to Cristoforo Sorte and to Antonio da Ponte, who had already been in charge of the one for the Senate Hall.[194] Sorte, dissatisfied with the way the project he had drawn up had been executed, protested (documents attesting to this protest date back to August 11, 1579. ): it can be assumed that the reduction of the original project is related to the will of Antonio da Ponte.[196] The work of decoration went on for a long time, even beyond the year 1582.[194] The project of the paintings that were to decorate the walls was entrusted to Jacopo Contarini, Jacopo Marcello and Gerolamo de Bardi. A fundamental work for the understanding of this project is the Dichiaratione di tutte le istorie che si contengono nei quadri posti novamente nelle sale dello Scrutinio et del gran Consiglio del Palagio Ducale della Serenissima Republica di Vinegia, nella quale si ha piena intelligenza delle più segnalate vittorie, conseguite di varie nationi del mondo dai Vinitiani (Declaration of all the histories which are contained in the pictures placed again in the halls of the Scrutiny and the Great Council of the Ducal Palace of the Most Serene Republic of Venice, in which there is full insight into the most distinguished victories, achieved from various nations of the world by the Venetians) by Bardi himself.[195] The first decisions made by the three were to enrich the room with depictions of the arrival of Alexander III in Venice and of the peace he made with Frederick Barbarossa; it was also their proposal to depict just below the frieze the faces and coats of arms of the doges who had reigned until then.[194]

As far as the decoration of the ceilings was concerned, various themes (military victories, deeds of citizens, allegories) were exploited, for each of which specific spaces were identified: in the Hall of the Scrutiny and the Hall of the Great Council, respectively, to the first theme the first and second sections were dedicated, to the second theme the second and last, and to the third theme the last and first.[196] Considering that a large part of the paintings were of a historical theme, a strict chronological succession was established not only between the canvases of the individual rooms, but also by creating a system involving both halls; in order to make the reading of the individual works clearer, they were painted using different hues: on the whole, the decorative cycles of the two rooms seem therefore to be concatenated.[196] The artists who were designated for the realization of this decorative apparatus were: Paolo and Benedetto Caliari, Jacopo and Domenico Robusti, Jacopo Palma il Giovane, Francesco Bassano, Antonio Aliense, Francesco Montemezzano, Giulio Del Moro, Andrea Vicentino, Marco Vecellio, Leonardo Corona, Girolamo Gambarato, Pietro Longo, Girolamo Padovano, Federico Zuccaro, Camillo Ballini, Tiburzio Bolognese, Paolo Fiammingo, and Francesco Terzo: however, not all of them worked on the site, due to death or impossibility.[197]

Last construction sites in the palace[edit]

Late 16th century and early 17th century[edit]

The work of modernizing the facades was completed between 1571 and 1579 when, to celebrate a grand Venetian victory over the Ottomans, the balconies facing the square and the pier were respectively decorated at their tops with allegorical statues of Venice and Justice.[197] By 1597 the replacement of the copper constituting the roof with a lead roofing was completed, due to infiltration in the Halls of the Great Council and the Scrutiny.[197] The conclusion of the sixteenth century was marked by the closure of some small construction sites begun some time earlier in the rooms damaged by the fire of 1574.[197]

The years at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were marked by the emergence in the Senate of the desire to relocate the prisons, then located on the first floor of the palace, first hinted at in asking for an opinion on the matter from the many experts who intervened in the restoration.[198] Factors that slowed down the start of said construction site were the disagreement between architects and the cost of the fund located beyond the Rio di Palazzo.[198] The first decree, promulgated in 1587, saw its effects in 1589.[198] A plan of the first floor of the palace was made in 1580 by Gianmaria dei Piombi: rediscovered by Giovanni Lorenzi, coadjutor of the Marciana Library around the middle of the nineteenth century, it is fundamental in the first place for understanding the history of the building, depicting its plan and the buildings located across the Rio, destined to be acquired for the building of the Prisons,[199] and secondly because it makes possible a critical reading of the many works that, written in different historical periods, had as their purpose the description of the building. With the help of such a plan it was possible to note the errors made by Abbot Pietro Bettio in his work Del Palazzo Ducale in Venezia. Lettera discorsiva, in which he describes the structure of the Scala Foscara (a staircase later demolished, which connected the second floor of the palace and the court by pairing with the so-called Scala di Pietra on which Marino Faliero's death sentence was carried out)[200] based on information in Cesare Vecellio's work Degli abiti antichi e moderni.[198] Bettio, however, misinterpreted Vecellio's writing and changed the plan and position of the staircase, also considering it to be contemporary with the neighboring loggia, which was actually built only later.[201] Also from this plan, it appears that prior to the early 17th-century renovation there were four rooms adjacent to the small square, used as dogal stables.[202]

The building site of the New Prisons was first conducted by Antonio da Ponte, upon whose death in 1597 Antonio Contin took over as director and completed the work in 1602: after the inmates moved to their new home, the first floor plan of the palace was readjusted, largely according to Andrea Palladio's design.[203] The New Prisons, the seat of the Lords of the Night, magistrates in charge of preventing and repressing criminal offenses, was connected to the palace by the Bridge of Sighs, crossed by convicts brought from the palace, seat of the courts, to the prisons.[204]

The space left vacant by the prisons was renovated by chief architect Bartolomeo Manopola, who took over that position after the death of da Ponte, but was almost forgotten by artistic historiography, mentioned neither by Francesco Milizia, nor by Filippo De Boni, nor by Giuseppe Cadorin, only mentioned by Giannantonio Moschini, by Leopoldo Cicognara and by Pietro Selvatico.[205] His work in the palace has been treated with errors and inaccuracies by the various historians, and especially by Cicognara. In fact, he did not demolish the Scala Foscara first, but he had a portico built in place of the load-bearing wall that supported the southern wing of the palace (and thus also the Hall of the Great Council), similar to the one designed by Rizzo; the completion of these works can be dated to the dogate of Leonardo Donà and more precisely to 1607 because of the presence of coats of arms and because of what the chronicles mention.[205] Also from the study of the decorations of the capitals of this portico, it can be stated that the superintendents in charge of supervising the work were Domenico Dolfin, Benedetto Moro and Antonio Priuli, later Doge, and that the work was not begun until 1606, since Dolfin and Moro only assumed that office in that year.[206]

Having completed this first work, work began along the western front of the courtyard, knocking down the Scala Foscara, the squires' dwellings, and then the wall below the Scrutiny Hall, promptly replaced by arches, in accordance with the other facades.[206] Even in the description of this phase of the work one encounters an error by Cicognara, who claimed to have replaced with round arches the hypothetical pre-existing loggias with pointed arches, which never existed.[206] These works were completed by 1610. Thus Pietro Bettio was wrong in asserting that the demolition work was not completed until 1618: this is because the portico bears the coat of arms of Leonardo Donà, doge in 1610, and not of Nicolò Donà, doge during the years to whom Bettio traced the work.[206] Offices for the magistracies of the five Sages and the Magistrate of the Waters were created in the freed spaces, and the squires' dwellings were renovated: all these works were completed by 1612.[207]

With the work site that had involved the western façade concluded and the Scala Foscara demolished, the short northern front remained, which, by virtue of the recent renovations that had involved the other elevations, now seemed rather bare:[207] in the space that connects the façade of the Arco Foscari on the courtyard and the corner of the palace, a façade opened by a large arcade on the first floor was erected (which, according to Manopola's order, was to stylistically trace the pre-existing loggias).[204][207] Following Manopola's orders, since the ground-floor loggia had to adapt to the narrow spaces and conform to the arches present in the adjacent atrium (leading from the Piazzetta to the Cortile), it was necessary to build only three arches per level, with round arches on the lower level and pointed arches on the upper level: considering that there were large spaces between the various arches, niches were built, enriched with statues offered by Federico Contarini.[208] The work was further decorated with the realization of a frieze that echoed that of the eastern front:[208] this first phase of the building site could be said to have been completed in 1615, since in the center of the frieze, between the two shields with the coat of arms of Doge Marcantonio Memmo, was written MARCO ANT. MEMMO DVCE ANNO DNI MDCXV.[208] At that time the top part with the clock had yet to be built, which was completed only under Giovanni Bembo, Marcantonio Memmo's successor.[209]

The construction site that had seen the demolition of the Foscara Staircase revealed that the right side of the Foscari Arch, built under the dogates of Francesco Foscari and Cristoforo Moro and at the same time as the aforementioned staircase, lacked decorations, as it was covered by the staircase.[208] The addition clearly differs from the rest of the arch in that it presents a different style, as well as in the fact that it was not depicted by Cesare Vecellio: it included the creation of a niche containing a female statue, which was made by sculpting the figure of Minerva, later replaced by a simulacrum of Ulpia Marciana.[208] Under Giovanni Bembo the worksite related to the decoration of that front was completed with the realization of the famous clock: this work, at first traced by Bettio and Cicognara to the dogates of Memmo or that of Nicolò Donà, is nevertheless to be attributed to the latter period because of the presence of a coat of arms of the aforementioned doge.[208]

17th century[edit]

The dogate of Antonio Priuli began with the renovation of the Doge's Apartment, and more precisely with the creation of a room dedicated to the traditional banquets that the doge offered to the highest state officials in the house of the Canons of the adjoining basilica.[210] This room was connected by the Manopola with a face stretched between the Stucchi Hall or Priuli Hall and the building mentioned above: after a few years, with the demolition of this bridge, the two buildings were definitively separated.[210] After the realization of this room, Francesco Maria II Della Rovere having donated to the Serenissima a statue of his ancestor Francesco Maria I Della Rovere, it was placed in the courtyard.[211] After this work, dating from 1625, no other work of great importance was completed in the palace.[212] It was embellished with a small altar dedicated to the Virgin and with two canvases, depicting The Scourge of the Plague and Saints Mark, Roch, Theodore and Sebastian, the former probably the work of Daniel van den Dyck, the latter of Baldassare d'Anna, the atrium of the Porta del Frumento;[212] was decorated under Francesco Erizzo, between 1631 and 1645, a room in the doge's apartment later known as the Sala Erizzo;[212] a triumphal arch dedicated to Francesco Morosini, decorated by Gregorio Lazzarini with six paintings, located in the Scrutiny Hall and bearing the inscription FRANCESCO MAVROCENO PELOPONNESIACO SENATUS ANNO MDCVIC, was made, possibly by Andrea Tirali.[213]

18th century[edit]

Also in the 18th century, no work worthy of special note was carried out: in 1728, under Alvise III Sebastiano Mocenigo, the Giants' Staircase was restored, with special care given to the plinths of the statues of Mars and Neptune, on which were written the date of the restoration and the commissioner;[213] on January 8, 1737 a fire struck the palace, and the extension made in the adjoining building during the previous renovation was demolished;[214] in 1741 the decoration of the Priuli Room was provided with paintings surrounded by stuccoes, eponymous ever since of that room;[214] about 1752 the five archaic windows of the southern and western fronts facing the courtyard, two in the Scrutiny Hall, two in that of the Great Council, and one in the doorway joining them, were replaced, to the aesthetic detriment of the complex;[214] in 1761 two of the maps in the Hall of the Shield, which had become ruined, were replaced, and this room was separated from the Hall of the Philosophers; under Alvise Mocenigo the Hall of the Banquets, built in the previous century but then torn down, was renovated;[215] in 1793 Pietro Antonio Novelli oversaw the restoration of some of the paintings adorning the Golden Staircase.[215]

After the fall of the Serenissima[edit]

19th century[edit]