History of U.S. foreign policy, 1776–1801

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1776 to 1801 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the twenty five years after the United States Declaration of Independence (1776). For the first half of this period, the U.S. f8, U.S. foreign policy was conducted by the presidential administrations of George Washington and John Adams. The inauguration of Thomas Jefferson in 1801 marked the start of the next era of U.S. foreign policy.

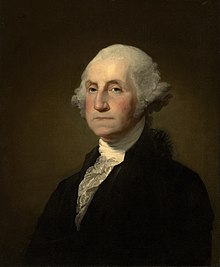

Following the ratification of the United States Constitution, George Washington took office in 1789. That same year, the French Revolution erupted, eventually leading to years of warfare between France, Britain, and other European powers that would continue until 1815. The French Revolution deeply split the United States, as Democratic-Republicans like Thomas Jefferson favored France and the revolution, while Federalists like Alexander Hamilton abhorred the revolution and favored Britain. As a neutral power, the United States sought to trade with both countries, but French and British ships attacked American ships trading with their respective enemies. President Washington sought to avoid foreign entanglement, issuing the Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793. In 1795, the Washington administration negotiated the Jay Treaty, under which the British agreed to open some ports to U.S. trade and evacuate western forts in U.S. territory. That same year, the Washington administration concluded the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain, settling borders disputes and granting American ships unrestricted navigation rights on the Mississippi River. In 1798, an undeclared naval war with France known as the Quasi-War broke out after France escalated attacks on American shipping. The war came to a close with the signing of the Convention of 1800, but attacks on American shipping by France and Britain would resume during the 19th century.

Leadership[edit]

Second Continental Congress, 1775–1781[edit]

The Second Continental Congress served as the governing body of the United States from the outbreak of the war in 1775 to the ratification of the Articles of Confederation in 1781.

Congress of the Confederation, 1781–1789[edit]

In 1776 Congress created a committee to craft a constitution for the new nation. The resulting constitution, which came to be known as the Articles of Confederation, provided for a weak national government with little power to coerce the state governments.[1] Under the Articles, states were forbidden from negotiating with other nations or maintaining a military without Congress's consent, but almost all other powers were reserved for the states.[2] Congress lacked the power to impose taxes or tariffs, and was incapable of enforcing its own legislation and instructions. As such, Congress was heavily reliant on the compliance and support of the states.[3] The weakness of Congress led to frequent talk of secession, and there was speculation that the new nation would break into four confederacies, consisting of New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, the Southern states, and the trans-Appalachian region, respectively.[4]

In early 1781, Congress created executive departments to handle foreign affairs, the military, and finances.[5] Robert Morris, appointed as superintendent of finance in 1781, won passage of major centralizing reforms such as the partial assumption of state debts, the suspension of payments to military personnel, and the creation of the Bank of North America. Morris emerged as the most powerful individual in the national government, with some referring to him as "The Financier."[6] After some of his proposals were blocked, Morris resigned in frustration in 1784, and was succeeded by a three-person Treasury Board.[7] Robert Livingston served as the Secretary of Foreign Affairs from 1781 to 1783, and he was followed in office by John Jay, who served from 1784 to 1789. Jay proved to be an able administrator, and he took control of the nation's diplomacy during his time in office.[8] In 1776, the Continental Congress had drafted the Model Treaty, which served as a guide for U.S. foreign policy during the 1780s. The treaty sought to abolish trade barriers such as tariffs, while avoiding political or military entanglements.[9]

Washington administration, 1789–1797[edit]

George Washington took office in 1789 after winning the 1788 presidential election unanimously. The new Constitution empowered the president to appoint executive department heads with the consent of the Senate.[10] The four positions of Secretary of War, Secretary of State, Secretary of Treasury, and Attorney General became collectively known as the cabinet, and Washington held regular cabinet meetings throughout his second term.[11] Washington initially offered the position of Secretary of State to John Jay, but after Jay expressed his preference for a judicial appointment, Washington selected Jefferson as the first permanent Secretary of State.[12] For the key post of Secretary of the Treasury, which would oversee economic policy, Washington chose Alexander Hamilton, after his first choice, Robert Morris, declined.[13] Hamilton and Jefferson had the greatest impact on cabinet deliberations during Washington's first term, and their deep philosophical differences set them against each other from the outset.[14]

Washington considered himself to be an expert in both foreign affairs and the Department of War, and as such, according to Forrest McDonald, "he was in practice his own Foreign Secretary and War Secretary."[15] Jefferson left the cabinet at the end of 1793,[16] and was replaced by Edmund Randolph.[17] Like Jefferson, Randolph tended to favor the French in foreign affairs, but he held very little influence in the cabinet.[18] Knox, Hamilton, and Randolph all left the cabinet during Washington's second term; Randolph was forced to resign during the debate over the Jay Treaty. Timothy Pickering succeeded Knox as Secretary of War, while Oliver Wolcott became Secretary of the Treasury and Charles Lee took the position of Attorney General.[19] In 1795, Pickering became the Secretary of State, and James McHenry replaced Pickering as Secretary of War.[20]

Adams administration, 1797–1801[edit]

John Adams took office in 1797 after winning the 1796 presidential election. Rather than seize the opportunity to use patronage to build a loyal group of advisors, Adams retained Washington's cabinet, although none of its members had ever been close to him.[21] Three cabinet members, Timothy Pickering, James McHenry, and Oliver Wolcott Jr., were devoted to Hamilton and referred every major policy question to him in New York. These cabinet members, in turn, presented Hamilton's recommendations to the president, and often actively worked against Adams's proposals.[22] As a split grew between Adams and the Hamiltonian wing of the Federalists during the second half of Adams's term, the president relied less on the advice of Pickering, McHenry, and Wolcott.[23] Upon apprehending the scope of Hamilton's behind the scenes manipulations, Adams dismissed Pickering and McHenry in 1800, replacing them with John Marshall and Samuel Dexter, respectively.[24]

Background: colonial diplomacy[edit]

Before the Revolutionary War, extra-colonial relations were handled in London.[25] The colonies had agents in the United Kingdom,[26] and established inter-colonial conferences. The colonies were subject to European peace settlements, settlements with Indian tribes, and inter-colony (between colonies) agreements.[27]

American Revolution[edit]

The American Revolutionary War broke out against British rule in April 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord.[28] The Second Continental Congress met in May 1775, and established an army funded by Congress and under the leadership of George Washington, a Virginian who had fought in the French and Indian War.[29] On July 4, 1776, as the war continued, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence.[30] Britain's diplomacy failed in the war—it had support of only a few small German states that hired out mercenaries. Most of Europe was officially neutral, but the elites and public opinion typically favoured the underdog American Patriots as in Sweden[31] and Denmark.[32]

France[edit]

Early in 1776, Silas Deane was sent to France, by Congress in a semi-official capacity, to induce the French government to lend its financial aid to the colonies. On arriving in Paris, Deane at once opened negotiations with Vergennes, and Beaumarchais, securing through Roderigue Hortalez and Company, the shipment of many arms and munitions to America. He also enlisted the services of a number of Continental soldiers of fortune, among whom were Lafayette, Baron Johann de Kalb, Thomas Conway, Casimir Pulaski, and Baron von Steuben.[citation needed]

Arthur Lee, was appointed correspondent of Congress in London in 1775. He was dispatched as an envoy to Spain and Prussia to gain their support for the rebel cause.[33] King Frederick the Great strongly disliked the British, and impeded its war effort in subtle ways, such as blocking the passage of Hessians. However, British trade was too important to lose, and there was risk of attack from Austria, so he pursued a peace policy and officially maintained strict neutrality.[34][35] Spain was willing to make war on Britain, but pulled back from full-scale support of the American cause because it intensely disliked republicanism, which was a threat to its Latin American Empire.[36]

In December 1776, Benjamin Franklin was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States. Franklin, with his charm offensive, was negotiating with Vergennes, for increasing French support, beyond the covert loans and French volunteers. With the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, the French formalized the alliance against their British enemy; Conrad Alexandre Gérard de Rayneval conducted the negotiations with the American representatives, Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. Signed on February 6, 1778, it was a defensive alliance where the two parties agreed to aid each other in the event of British attack. Further, neither country would make a separate peace with London, until the independence of the Thirteen Colonies was recognized.[37][38]

The French strategy was ambitious, and even a large-scale invasion of Britain was contemplated. France believed it could defeat the British within two years.[39] In March 1778, Gérard de Rayneval sailed to America with d'Estaing's fleet; he received his first audience of Congress on August 6, 1778, as the first accredited Minister from France to the United States.[40] French aid proved pivotal to American success in the Revolutionary War.[citation needed]

Spain[edit]

Spain was not an ally of the United States, (although an informal alliance had existed since at least 1776 between the Americans and Bernardo de Gálvez, Spanish governor of Louisiana, one of the most successful leaders in the entire war).[41] In 1777, a new prime minister, José Moñino y Redondo, Count of Floridablanca, had come to power, and had a reformist agenda that drew on many of the English liberal traditions. The French relied upon the Bourbon Family Compact, an alliance that had been in place since the Bourbons had become Spain's ruling dynasty in 1713. The Treaty of Aranjuez was signed on 12 April 1779; France agreed to aid in the capture of Gibraltar, Florida, and the island of Menorca. On 21 June 1779, Spain declared war on England.

Spain's economy depended almost entirely on its colonial empire in the Americas, and they were worried about the United States' territorial expansion. With such considerations in mind, Spain persistently rebuffed John Jay's attempts to establish diplomatic relations. Spain was one of the last participants of the American Revolutionary War to acknowledge the independence of the United States, on 3 February 1783. Britain recognized the independence of the United States in the Treaty of Paris, officially ending the American Revolution, signed 3 September 1783. The US established diplomatic relations with London in 1785. John Adams, who would later become the second president of the United States, was the first American emissary to Great Britain.

The Dutch Republic[edit]

In 1776, the United Provinces were the first country to salute the Flag of the United States, leading to growing British suspicions of the Dutch. In 1778 the Dutch refused to be bullied into taking Britain's side in the war against France. The Dutch were major suppliers of the Americans: in 13 months from 1778 to 1779, for example, 3,182 ships cleared the island of Sint Eustatius, in the West Indies.[42] When the British started to search all Dutch shipping for weapons for the rebels, the Republic officially adopted a policy of armed neutrality. Britain declared war in December 1780,[43] before the Dutch could join the League of Armed Neutrality. This resulted in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, which diverted British resources, but ultimately confirmed the decline of the Dutch Republic.[44]

In 1782 John Adams negotiated loans of $2 million for war supplies, by Dutch bankers. On March 28, 1782, after a petition campaign on behalf of the American cause organised by Adams and the Dutch patriot politician Joan van der Capellen, the United Netherlands recognized American independence, and subsequently signed a treaty of commerce and friendship.[45]

Canada[edit]

The Letters to the inhabitants of Canada were three letters written by the First and Second Continental Congresses in 1774, 1775, and 1776 to communicate directly with the population of the Province of Quebec, formerly the French province of Canada, which had no representative system at the time. Their purpose was to draw the large French-speaking population to the American revolutionary cause. This goal ultimately failed, and Quebec, along with the other northern provinces of British America remained in British hands. The only significant assistance that was gained was the recruitment of two regiments totalling less than 1,000 men.[citation needed]

Neutrals[edit]

The First League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance of minor European naval powers between 1780 and 1783 which was intended to protect neutral shipping against the British Royal Navy's wartime policy of unlimited search of neutral shipping for French contraband.[46] Empress Catherine II of Russia began the first League with her declaration of Russian armed neutrality on 11 March (28 February, Old Style), 1780, during the War of American Independence. She endorsed the right of neutral countries to trade by sea with nationals of belligerent countries without hindrance, except in weapons and military supplies. Russia would not recognize blockades of whole coasts, but only of individual ports, and only if a belligerent's warship were actually present or nearby. The Russian navy dispatched three squadrons to the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and North Sea to enforce this decree. Denmark and Sweden, accepting Russia's proposals for an alliance of neutrals, adopted the same policy towards shipping, and the three countries signed the agreement forming the League. They remained otherwise out of the war, but threatened joint retaliation for every ship of theirs searched by a belligerent. When the Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1783, Prussia, the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Ottoman Empire had all become members. As the British Navy outnumbered all their fleets combined, the alliance as a military measure was what Catherine later called it, an "armed nullity". Diplomatically, however, it carried greater weight; France and the United States of America were quick to proclaim their adherence to the new principle of free neutral commerce.[citation needed]

Treaty of Paris 1783[edit]

After the American victory at the Battle of Yorktown in September 1781 and the collapse of British Prime Minister North's ministry in March 1782, both sides sought a peace agreement.[47] The American Revolutionary War ended with the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The treaty granted the United States independence, as well as control of a vast region south of the Great Lakes and extending from the Appalachian Mountains west to the Mississippi River. Although the British Parliament had attached this trans-Appalachian region to Quebec in 1774 as part of the Quebec Act, several states had land claims in region based on royal charters and proclamations that defined their boundaries as stretching "from sea to sea."[48] Some Americans had hoped the treaty would provide for the acquisition of Florida, but that territory was restored to Spain, which had joined the U.S. and France in the war against Britain and demanded its spoils.[49] The British fought hard and successfully to keep Canada, so the treaty acknowledged that.[50]

Observers at the time and historians ever since emphasize the generosity of British territorial concessions. Historians such as Alvord, Harlow, and Ritcheson have emphasized that Britain's generous territorial terms were based on a statesmanlike vision of close economic ties between Britain and the United States. The treaty was designed to facilitate the growth of the American population and create lucrative markets for British merchants, without any military or administrative costs to Britain.[48] As the French foreign minister Vergennes later put it, "The English buy peace rather than make it".[51]

The treaty also addressed several additional issues. The United States agreed to honor debts incurred prior to 1775, while the British agreed to remove their soldiers from American soil.[49] Privileges that the Americans had received because of their membership in the British Empire no longer applied, most notably protection from pirates in the Mediterranean Sea. Neither the Americans nor the British would consistently honor these additional clauses. Individual states ignored treaty obligations by refusing to restore confiscated Loyalist property, and many continued to confiscate Loyalist property for "unpaid debts". Some states, notably Virginia, maintained laws against payment of debts to British creditors. The British often ignored the provision of Article 7 regarding removal of slaves.[52]

Western settlement in the 1780s[edit]

Partly due to the restrictions imposed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, only a handful of Americans had settled west of the Appalachian Mountains prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The start of that war lifted the barrier to settlement, and by 1782 approximately 25,000 Americans had settled in Transappalachia.[53] After the war, American settlement in the region continued. Though life in these new lands proved hard for many, western settlement offered the prize of property, an unrealistic aspiration for some in the East.[54]

Though Southern leaders and many nationalists lent their political support to the settlers, most Northern leaders were more concerned with trade than with western settlement, and the weak national government lacked the power to compel concessions from foreign governments. The 1784 closure of the Mississippi River by Spain denied access to the sea for the exports of Western farmers, greatly impeding efforts to settle the West, and they provided arms to Native Americans.[55] In western territories—chiefly in present-day Wisconsin and Michigan—the British retained control of several forts and continued to cultivate alliances with Native Americans.[56] These policies impeded U.S. settlement and allowed Britain to extract profits from the lucrative fur trade.[57] The British justified their continued occupation of the forts on the basis that the American had blocked the collection of pre-war debts owed to British citizens.[58] Between 1783 and 1787, hundreds of settlers died in low-level conflicts with Native Americans, and these conflicts discouraged further settlement.[55] As Congress provided little military support against the Native Americans, most of the fighting was done by the settlers.[59] By the end of the decade, the frontier was engulfed in the Northwest Indian War against a confederation of Native American tribes.[60] These Native Americans sought the creation of an independent Indian barrier state with the support of the British, posing a major foreign policy challenge to the United States.[61]

Economy and trade in the 1780s[edit]

A brief economic recession followed the war, but prosperity returned by 1786.[62] Trade with Britain resumed, and the volume of British imports after the war matched the volume from before the war, but exports fell precipitously.[54] Adams, serving as the ambassador to Britain, called for a retaliatory tariff in order to force the British to negotiate a commercial treaty, particularly regarding access to Caribbean markets. However, Congress lacked the power to regulate foreign commerce or compel the states to follow a unified trade policy, and Britain proved unwilling to negotiate.[63] While trade with the British did not fully recover, the U.S. expanded trade with France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and other European countries. Despite these good economic conditions, many traders complained of the high duties imposed by each state, which served to restrain interstate trade. Many creditors also suffered from the failure of domestic governments to repay debts incurred during the war.[54] Though the 1780s saw moderate economic growth, many experienced economic anxiety, and Congress received much of the blame for failing to foster a stronger economy.[64]

French Revolution 1789-1796[edit]

Public debate[edit]

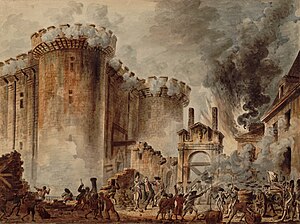

With the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the French Revolution erupted. The American public, remembering the aid provided by the French during the Revolutionary War, was largely enthusiastic, and hoped for democratic reforms that would solidify the existing Franco-American alliance and transform France into a republican ally against aristocratic and monarchical Great Britain.[65] Shortly after the Bastille fell, the main prison key was turned over to the Marquis de Lafayette, a Frenchman who had served under Washington in the American Revolutionary War. In an expression of optimism about the revolution's chances for success, Lafayette sent the key to Washington, who displayed it prominently in the executive mansion.[66] In the Caribbean, the revolution destabilized the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), as it split the government into royalist and revolutionary factions, and aroused the people to demand civil rights for themselves. Sensing an opportunity, the slaves of northern St. Domingue organized and planned a massive rebellion which began on August 22, 1791. Their successful revolution resulted in the establishment of the second independent country in the Americas (after the United States).[67] Soon after the revolt began, the Washington administration, at French request, agreed to send money, arms, and provisions to Saint-Domingue to assist distressed slave-owning colonists.[68] Reacting to reports spread by fleeing Frenchmen of Haitian slaves murdering people, many Southerners believed that a successful slave revolt in Haiti would lead to a massive race war in America.[69] American aid to Saint-Domingue formed part of the US repayment of Revolutionary War loans, and eventually amounted to about $400,000 and 1,000 military weapons.[70]

From 1790 to 1794, the French Revolution became increasingly radical.[65] In 1792 the revolutionary government declared war on several European nations, including Great Britain, starting the War of the First Coalition. A wave of bloody massacres spread through Paris and other cities late that summer, leaving more than one thousand people dead. On September 21, 1792, France declared itself a republic, and the deposed King Louis XVI was guillotined on January 21, 1793. Then followed a period labeled by some historians as the "Reign of Terror," between the summer of 1793 and the end of July 1794, during which 16,594 official death sentences were carried out against those accused of being enemies of the revolution.[71] Among the executed were persons who had aided the American rebels during the Revolutionary War, such as the navy commander Comte D'Estaing.[72] Lafayette, who was appointed commander-in-chief of the National Guard following the storming of the Bastille, fled France and ended up in captivity in Austria,[73] while Thomas Paine, in France to support the revolutionaries, was imprisoned in Paris.[74]

Though originally most Americans were in support of the revolution, the political debate in the U.S. over the nature of the revolution soon exacerbated pre-existing political divisions and resulted in the alignment of the political elite along pro-French and pro-British lines. Thomas Jefferson became the leader of the pro-French faction that celebrated the revolution's republican ideals. Though originally in support of the revolution, Alexander Hamilton soon led the faction which viewed the revolution with skepticism (believing that "absolute liberty would lead to absolute tyranny") and sought to preserve existing commercial ties with Great Britain.[65][75] When news reached America that France had declared war on the British, people were divided on whether the U.S. should enter the war on the side of France. Jefferson and his faction wanted to aid the French, while Hamilton and his followers supported neutrality in the conflict. Jeffersonians denounced Hamilton, Vice President Adams, and even the president as friends of Britain, monarchists, and enemies of the republican values that all true Americans cherish.[76][77] Hamiltonians warned that Jefferson's Republicans would replicate the terrors of the French revolution in America – "crowd rule" akin to anarchy, and the destruction of "all order and rank in society and government."[78]

Genet Affair and neutrality 1793[edit]

Although President Washington sought to avoid any and all foreign entanglements,[79] a sizable portion of the American public was ready to help the French and their fight for "liberty, equality, and fraternity." In the days immediately following Washington's second inauguration, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt's mission was to drum up support for the French cause. Genêt issued letters of marque and reprisal to 80 American merchant ships so they could capture British merchant ships.[80] He held large fervent rallies where Americans hurrahed for France and booed mention of President Washington. He fought against neutrality and created a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities.[81]

Washington was deeply irritated by this subversive meddling, and when Genêt allowed a French-sponsored warship to sail out of Philadelphia against direct presidential orders, Washington demanded that France recall Genêt. Jefferson agreed. By this time the revolution had taken a more violent approach and Genêt would have been executed had he returned to France. Washington allowed him to remain, making him the first political refugee to seek sanctuary in the United States.[82]

Washington, after consulting his Cabinet, issued a Proclamation of Neutrality on April 22, 1793. In it he declared the United States neutral in the conflict between Great Britain and France. He also threatened legal proceedings against any American providing assistance to any of the warring countries. Washington eventually recognized that supporting either Great Britain or France was a false dichotomy. He would do neither, thereby shielding the fledgling U.S. from, in his view, unnecessary harm.[83] The Proclamation was formalized into law by the Neutrality Act of 1794.[84]

The public had mixed opinions about Washington's Proclamation of Neutrality. Genêt had roused many Americans, making foreign policy a high priority issue. Supporters of Jefferson generally opposed Britain and supported the French Revolution, welcoming an old nation to achieving liberty from tyrannical rule. However merchants worried that a support for France would ruin their trade with the British. This economic element was a primary reason for many Federalist supporters wanting to avoid increased conflict with the British.[85] Meanwhile Hamilton used the popular reaction against Genêt to build support for his anti-French Federalist faction.[86] The events were known as the Genet Affair or French Neutrality Crisis.[87]

British seizures[edit]

Upon going to war against France, the British Royal Navy began intercepting ships of neutral countries bound for French ports. The French imported large amounts of American foodstuffs, and the British hoped to starve the French into defeat by intercepting these shipments.[88] In November 1793, the British government widened the scope of these seizures to include any neutral ships trading with the French West Indies, including those flying the American flag.[89] By the following March, more than 250 U.S. merchant ships had been seized.[90] Americans were outraged, and angry protests erupted in several cities.[91] Many Jeffersonians in Congress demanded a declaration of war, but Congressman James Madison instead called for strong economic retaliation, including an embargo on all trade with Britain.[92] Further inflaming anti-British sentiment in Congress, news arrived while the matter was under debate that the Governor General of British North America, Lord Dorchester, had made an inflammatory speech inciting Native tribes in the Northwest Territory against the Americans.[89][92][a]

Congress responded to these "outrages" by passing a 30-day embargo on all shipping, foreign and domestic, in American harbors.[90] In the meantime, the British government had issued an order in council partially repealing effects of the November order. This policy change did not defeat the whole movement for commercial retaliation, but it cooled passions somewhat. The embargo was later renewed for a second month, but then was permitted to expire.[94] In response to Britain's more conciliatory policies, Washington named Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay as special envoy to Great Britain in an effort to avoid war.[95] This appointment provoked the ire of Jeffersonians. Although confirmed by a comfortable margin in the U.S. Senate (18–8), debate on the nomination was bitter.[96]

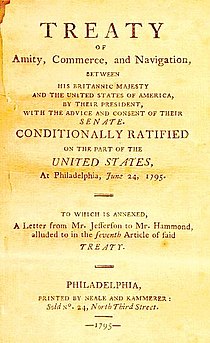

Jay Treaty 1796[edit]

Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London in 1794 to negotiate a treaty with Britain. Jay was instructed by Hamilton to seek compensation for seizure of American ships and to clarify the rules governing British seizure of neutral ships. He was also to insist that the British relinquish their posts in the Northwest. In return, the U.S. would take responsibility for pre-Revolution debts owed to British merchants and subjects. He also asked Jay, if possible, to seek limited access for American ships to the British West Indies.[89] Jay and the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville, began negotiations on July 30, 1794. The treaty that emerged several weeks later, known as the Jay Treaty, was, in Jay's words "equal and fair."[97] Both sides achieved many objectives; several issues were sent to arbitration. For the British, America remained neutral and economically grew closer to Britain. The Americans also guaranteed favorable treatment to British imports. In return, the British agreed to evacuate the western forts, which they had been supposed to do by 1783. They also agreed to open their West Indies ports to smaller American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies, and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships, and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775. As the treaty contained neither concessions on impressment nor statement of rights for American sailors, another commission was later established to settle both those and boundary issues.[98]

Once the treaty arrived in Philadelphia in March 1795, Washington—who had misgivings about the treaty's terms—kept its contents confidential until June, when a special session of the Senate convened to give its advice and consent. Peter Trubowitz writes that during these several months Washington wrestled with "a strategic dilemma," balancing geopolitics and domestic politics. "If he threw his support behind the treaty, he risked destroying his fragile government from within due to partisan rage. If he shelved the treaty to silence his political detractors, there would likely be war with Great Britain, which had the potential to destroy the government from the outside."[99] Submitted on June 8, debate on the treaty's 27 articles was carried out in secret, and lasted for more than two weeks.[100] Republican senators, who wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war,[101] denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, and a repudiation of the 1778 treaty with France; New York's Aaron Burr argued point-by-point why the whole agreement should be renegotiated. On June 24, the Senate approved the treaty by a vote of 20–10 – the precise two-thirds majority vote necessary for ratification.[100]

Although the Senate hoped to keep the treaty secret until Washington had decided whether or not to sign it, it was leaked to a Philadelphia editor who printed it in full on June 30.[100] Within a few days the whole the country knew the terms of the agreement, and, in the words of Samuel Morison, "a howl or rage went up that Jay had betrayed his country."[102] The reaction to the treaty was the most negative in the South. Southern planters, who owed the pre-Revolution debts to the British and who were now not going to collect for the slaves lost to them, viewed it as a great indignity. As a result, the Federalists lost most of the support they had among planters.[103] Protests, organized by Republicans, included petitions, incendiary pamphlets, and a series of public meetings held in the larger cities, each of which addressed a memorial to the president.[104] As protests from treaty opponents intensified, Washington's initial neutral position shifted to a solid pro-treaty stance, aided by Hamilton's elaborate analysis of the treaty and his two-dozen newspaper essays promoting it.[105] The British, in an effort to promote signing of the treaty, delivered a letter in which Randolph was revealed to have taken bribes from the French. Randolph was forced to resign from the cabinet, his opposition to the treaty became worthless. On August 24, Washington signed the treaty.[106]

There was a temporary lull in the Jay Treaty furor thereafter. By late 1796, the Federalists had gained twice as many signatures in favor of the treaty as had been gathered against. Public opinion had been swayed in favor of the treaty.[107] The following year, it flared up again when the House of Representatives inserted itself into the debate. The new debate was not only over the merits of the treaty, but also about whether the House had the power under the Constitution to refuse to appropriate the money necessary for a treaty already ratified by the Senate and signed by the president.[104] Citing its constitutional fiscal authority (Article I, Section 7), the House requested that the president turn over all documents that related to the treaty, including his instructions to Jay, all correspondence, and all other documents relating to the treaty negotiations. He refused to do so, invoking what later became known as executive privilege,[108] and insisted that the House did not have the Constitutional authority to block treaties.[100][109] A contentious debate ensued, during which Washington's most vehement opponents in the House publicly called for his impeachment.[103] Through it all, Washington responded to his critics by using his prestige, political skills, and the power of office in a sincere and straightforward fashion to broaden public support for his stance.[105] The Federalists heavily promoted the passage, waging what Forrest McDonald calls "The most intensive campaign of pressure politics the nation had yet known."[110] On April 30, the House voted 51–48 to approve the requisite treaty funding.[100] Jeffersonians carried their campaign against the treaty and "pro-British Federalist policies" into the political campaigns (both state and federal) of 1796, where the political divisions marking the First Party System became crystallized.[111] The treaty pushed the new nation away from France and towards Great Britain. The French government concluded that it violated the Franco-American treaty of 1778, and that the U.S. government had accepted the treaty despite the overwhelming public sentiment against it.[111]

Conflict with France[edit]

XYZ Affair[edit]

Adams's term was marked by disputes concerning the country's role, if any, in the expanding conflict in Europe, where Britain and France were at war.[112] In the 1796 elections, the French supported Jefferson for president, and they became even more belligerent at his loss.[113] Nevertheless, when Adams took office, pro-French sentiment in the United States remained strong due to France's assistance during the Revolutionary War.[114][115] Adams hoped to maintain friendly relations with France, and he sent a delegation to Paris, consisting of John Marshall, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry, to ask for compensation for the French attacks on American shipping. When the envoys arrived in October 1797, they were kept waiting for several days, and then finally granted only a 15-minute meeting with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. After this, the diplomats were met by three of Talleyrand's agents. Each refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes, one to Talleyrand personally, and another to the Republic of France.[116] The Americans refused to negotiate on such terms.[117] Marshall and Pinckney returned home, while Gerry remained.[118]

In an April 1798 speech to Congress, Adams publicly revealed Talleyrand's machinations, sparking public outrage at the French.[119] Democratic-Republicans were skeptical of the administration's account of what became known as the "XYZ affair." Many of Jefferson's supporters would undermine and oppose Adams's efforts to defend against the French.[120] Their main fear was that war with France would lead to an alliance with England, which in turn could allow the allegedly monarchist Adams to further his domestic agenda. For their part, many Federalists, particularly the conservative "ultra-Federalists," deeply feared the radical influence of the French Revolution. Economics also drove the divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, as Federalists sought financial ties with England, while many Democratic-Republicans feared the influence of English creditors.[121]

[edit]

The president saw no advantage in joining the British-led alliance against France. He therefore pursued a strategy whereby American ships harassed French ships in an effort sufficient to stem the French assaults on American interests, beginning an undeclared naval war known as the Quasi-War.[122] In light of the threat of invasion from the more powerful French forces, Adams asked Congress to authorize a major expansion of the navy and the creation of a twenty-five thousand man army. Congress authorized a ten-thousand man army and a moderate expansion of the navy, which at the time consisted of one unarmed custom boat.[123][124] Washington was commissioned as senior officer of the army, and Adams reluctantly agreed to Washington's request that Hamilton serve as the army's second-in-command.[125] It became apparent that Hamilton was truly in charge due to Washington's advanced years. The angered president remarked at the time, "Hamilton I know to be a proud Spirited, conceited, aspiring Mortal always pretending to Morality," he wrote, but "with as debauched Morals as old Franklin who is more his Model than anyone I know."[122] Due to his support for the expansion of the navy and the creation of the United States Department of the Navy, Adams is "often called the father of the American Navy".[126]

Led by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, the navy won several successes in the Quasi-War, including the capture of L'Insurgente, a powerful French warship. The navy also opened trade relations with Saint-Domingue (now known as Haiti), a rebellious French colony in the Caribbean.[127] Over the opposition of many in his own party, Adams resisted the escalation of the war. The president's continued support for Elbridge Gerry, a Democratic-Republican who Adams had sent to France at the beginning of his term and who continued to seek peace with the French, particularly frustrated many Federalists.[128] Hamilton's influence in the War Department also widened the rift between Federalist supporters of Adams and Hamilton. At the same time, the creation of a large standing army raised popular alarm and played into the hands of the Democratic-Republicans.[129]

In February 1799, Adams surprised many by announcing that he would send diplomat William Vans Murray on a peace mission to France. Adams delayed sending a delegation while he awaited the construction of several U.S. warships, which he hoped would alter the balance of power in the Caribbean. Much to the chagrin of Hamilton and other arch-Federalists, the delegation was finally dispatched in November 1799.[130] The president's decision to send a second delegation to France precipitated a bitter split in the Federalist Party, and some Federalist leaders began to look for an alternative to Adams in the 1800 presidential election.[131] The prospects for peace between the U.S. and France were bolstered by the ascent of Napoleon in November 1799, as Napoleon viewed the Quasi-War as a distraction from the ongoing war in Europe. In the spring of 1800, the delegation sent by Adams began negotiating with the French delegation, led by Joseph Bonaparte.[132]

The war came to a close in September when both parties signed the Convention of 1800, but the French refused to recognize the abdication of the Treaty of Alliance of 1778, which had created a Franco-American alliance.[133] The United States gained little from the settlement other than the suspension of hostilities with the French, but the timing of the agreement proved fortunate for the U.S., as the French would gain a temporary reprieve from war with Britain in the 1802 Treaty of Amiens.[134] News of the signing of the convention did not arrive in the United States until after the election. Overcoming the opposition of some Federalists, Adams was able to win Senate ratification of the convention in February 1801.[135] Having concluded the war, Adams demobilized the emergency army.[136]

Disputes with Spain[edit]

Spain fought the British as an ally of France during the Revolutionary War, but it distrusted the ideology of republicanism and was not officially an ally of the United States.[137] Spain controlled the territories of Florida and Louisiana, positioned to the south and west of the United States. Americans had long recognized the importance of navigation rights on the Mississippi River, as it was the only realistic outlet for many settlers in the trans-Appalachian lands to ship their products to other markets, including the Eastern Seaboard of the United States.[138]

Despite having fought a common enemy in the Revolutionary War, Spain saw republican expansionism as a threat to its empire. Seeking to stop the American settlement of the Old Southwest, Spain denied the U.S. navigation rights on the Mississippi River, provided arms to Native Americans, and recruited friendly American settlers to the sparsely populated territories of Florida and Louisiana.[139] Working with Alexander McGillivray, Spain signed treaties with Creeks, the Chickasaws, and the Choctaws to make peace among themselves and ally with Spain, but the pan-Indian coalition proved unstable.[140][141][142] Spain also bribed American General James Wilkinson in a plot to make much of the southwestern United States secede, but nothing came of it.[143]

In the late 1780s, Georgia grew eager to firm up its trans-Appalachian land claim, and meet citizen demands that the land be developed. The territory claimed by Georgia, which it called the "Yazoo lands," ran west from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, and included most of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi (between 31° N and 35° N). The southern portion of this region was also claimed by Spain as part of Spanish Florida. One of Georgia's efforts to accomplish its goals for the region was a 1794 plan developed by governor George Mathews and the Georgia General Assembly. It soon became a major political scandal, known as the Yazoo land scandal.[144][145]

After Washington issued his 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality he became concerned that Spain, which later that year joined Britain in war against France, might work in concert with Britain to incite insurrection in the Yazoo against the U.S., using the opening of trade on the Mississippi as an enticement.[146] At that same time though, mid-1794, Spain was attempting to extract itself from its alliance with the British, and to restore peace with France. As Spain's prime minister, Manuel de Godoy, was attempting to do so, he learned of John Jay's mission to London, and became concerned that those negotiations would result in an Anglo-American alliance and an invasion of Spanish possessions in North America. Sensing the need for rapprochement, Godoy sent a request to the U.S. government for a representative empowered to negotiate a new treaty; Washington sent Thomas Pinckney to Spain in June 1795.[147]

Eleven months after the signing of the Jay Treaty, the United States and Spain agreed to the Treaty of San Lorenzo, also known as Pinckney's Treaty. Signed on October 27, 1795, the treaty established intentions of peace and friendship between the U.S. and Spain; established the southern boundary of the U.S. with the Spanish colonies of East Florida and West Florida, with Spain relinquishing its claim on the portion of West Florida north of the 31st parallel; and established the western U.S. border as being along the Mississippi River from the northern U.S. to the 31st parallel.[148]

Perhaps most importantly, Pinckney's Treaty granted both Spanish and American ships unrestricted navigation rights along the entire Mississippi River, as well as duty-free transport for American ships through the Spanish port of New Orleans, opening much of the Ohio River basin for settlement and trade. Agricultural produce could now flow on flatboats down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and on to New Orleans. From there the goods could be shipped around the world. Spain and the United States further agreed to protect the vessels of the other party anywhere within their jurisdictions and to not detain or embargo the other's citizens or vessels.[149]

The final treaty also voided Spanish guarantees of military support that colonial officials had made to Native Americans in the disputed regions, greatly weakening those communities' ability to resist encroachment upon their lands.[147] The treaty represented a major victory for Washington administration, and placated many of the critics of the Jay Treaty. It also enabled and encouraged American settlers to continue their movement west, by making the frontier areas more attractive and lucrative.[150] The region that Spain relinquished its claim to through the treaty was organized by Congress as the Mississippi Territory on April 7, 1798.[151]

As war between France and the United States appeared possible, Spain was slow to implement the terms of the Treaty of San Lorenzo. Shortly after Adams took office, Senator William Blount's plans to drive the Spanish out of Louisiana and Florida became public, causing a deterioration in relations between the U.S. and Spain. Francisco de Miranda, a Venezuelan patriot, also attempted to stir up support for an American intervention against Spain, possibly with the help of the British. Rejecting Hamilton's ambitions for the seizure of Spanish territory, Adams refused to meet with Miranda, squashing the plot. Having avoided war with both France and Spain, the Adams administration oversaw the implementation of the Treaty of San Lorenzo.[152]

Barbary pirates[edit]

Following the end of the Revolutionary War the ships of the Continental Navy were gradually disposed of, and their crews disbanded. The frigate Alliance, which had fired the last shots of the war in 1783, was also the last ship in the Navy. Many in the Continental Congress wanted to keep the ship in active service, but the lack of funds for repairs and upkeep, coupled with a shift in national priorities, eventually prevailed over sentiment. The ship was sold in August 1785, and the navy disbanded.[153] At around the same time American merchant ships in the Western Mediterranean and Southeastern North Atlantic began having problems with pirates operating from ports along North Africa's so-called Barbary Coast – Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis. In 1784–85, Algerian pirate ships seized two American ships (Maria and Dauphin) and held their crews for ransom.[154][155] Thomas Jefferson, then Minister to France, suggested an American naval force to protect American shipping in the Mediterranean, but his recommendations were initially met with indifference, as were later recommendations of John Jay, who proposed building five 40-gun warships.[154][155]

Beginning late in 1786, the Portuguese Navy began blockading Algerian ships from entering the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar, which provided temporary protection for American merchant ships.[154][156] However in 1793 the Barbary pirates began to roam the Atlantic and soon captured 11 American vessels and more than a hundred seamen.[153][156]

In response to continued attacks on American shipping, Washington asked Congress to establish a standing navy.[157][158] After a contentious debate, Congress passed the Naval Armament Act on March 27, 1794, authorizing construction of six frigates (to be built by Joshua Humphreys). These ships were the first ships of what eventually became the present-day United States Navy.[153] Soon afterward, Congress also authorized funds to obtain a treaty with Algiers and to ransom Americans held captive (199 were alive at that time, including a few survivors from the Maria and the Dauphin). Ratified in September 1795, the final cost of the return of those held captive and peace with Algiers was $642,000, plus $21,000 in annual tribute. The president was unhappy with the arrangement, but realized the U.S. had little choice but to agree to it.[159] Treaties were also concluded with Tripoli, in 1796, and Tunis in 1797, each carrying with it an annual U.S. tribute payment obligation for protection from attack.[160] The new Navy would not be deployed until after Washington left office; the first two frigates completed were: United States, launched May 10, 1797; and Constitution, launched October 21, 1797.[161]

Notes[edit]

- ^ It was reported that in February 1794, the Governor General of British North America, Lord Dorchester, told leaders of the Seven Nations of Canada that war between the U.S. and Britain was likely to break out before the year was out. He also stated that, due to American aggression in the region, the U.S. had forfeited the region (south of the Great Lakes) awarded by 1783 Treaty of Paris.[93] Dorchester was officially reprimanded by the Crown for his strong and unsanctioned words.

References[edit]

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 177–179

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 25–26

- ^ Chandler (1990), pp. 434–435

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 273–274

- ^ Chandler (1990), pp. 443–445

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 235–242

- ^ Chandler (1990), p. 445

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 35–36

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 16–17

- ^ "The Constitution and the cabinet nomination process". National Constitution Center. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ Ellis 2016, p. 27

- ^ Bordewich 2016, pp. 159–160

- ^ Chernow 2004, p. 286

- ^ Ferling, John (February 15, 2016). "How the Rivalry Between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton Changed History". A version of this piece appears in TIME's special edition Alexander Hamilton: A Founding Father's Visionary Genius—and His Tragic Fate. New York City, New York: Time. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ McDonald 1974 p. 41

- ^ "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826)". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ McDonald 1974, pp. 139, 164–165

- ^ McDonald 1974, pp. 139

- ^ McDonald 1974, pp. 161, 164–165

- ^ Ferling 2003, pp. 406–407

- ^ Ferling 2004, 96–97

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 90–92

- ^ Brown 1975, p. 168

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 170–172

- ^ "The U.S. Republic's First Year of Foreign Policy – Archiving Early America". Earlyamerica.com. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ Elmer Plischke (1999). U.S. Department of State. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-313-29126-5.

- ^ Elmer Plischke (1999). U.S. Department of State. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-313-29126-5.

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 128–129

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 135, 141–144

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 175–176

- ^ H. A. Barton, "Sweden and the War of American Independence," William and Mary Quarterly (1966) 23#2 pp. 408–430 in JSTOR

- ^ Robert Rinehart, "Denmark Gets the News of '76," Scandinavian Review (1976) 63#2 pp 5–14

- ^ Louis W. Potts, Arthur Lee, A Virtuous Revolutionary (1981)

- ^ Paul Leland Haworth, "Frederick the Great and the American Revolution" American Historical Review (1904) 9#3 pp. 460–478 open access in JSTOR

- ^ Henry Mason Adams, Prussian-American Relations: 1775–1871 (1960).

- ^ Jonathan R. Dull (1987). A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution. Yale University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0300038860.

- ^ Hoffman, Ronald; Albert, Peter J., eds. (1981). Diplomacy and Revolution: the Franco-American Alliance of 1778. Charlottesville: Univ. Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0864-7.

- ^ Ross, Maurice (1976). Louis XVI, Forgotten Founding Father, with a survey of the Franco-American Alliance of the Revolutionary period. New York: Vantage Press. ISBN 0-533-02333-5.

- ^ Alfred Temple Patterson, The Other Armada: The Franco-Spanish Attempt to Invade Britain in 1779 (Manchester University Press, 1960).

- ^ "The Avalon Project : Treaty of Amity and Commerce". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ Harvey, Robert. A. Few Bloody Noses: The American Revolutionary War. p. 531.

- ^ "Dutch Arms in the American Revolution". 11thpa.org. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ^ Jeremy Black (1998). Why wars happen. Reaktion Books. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-86189-017-7.

- ^ Hamish M. Scott, "Sir Joseph Yorke, Dutch politics and the origins of the fourth Anglo-Dutch war." The Historical Journal 31#3 (1988): 571–589.

- ^ David G. McCullough (2001). John Adams. Simon and Schuster. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-684-81363-9.

Holland recognizes the United States.

- ^ Paul W. Mapp, "The Revolutionary War and Europe's Great Powers." in Edward G. Gray and Jane Kamensky, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2013): pp 311–26.

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 241–242

- ^ a b Charles R. Ritcheson, "The Earl of Shelbourne and Peace with America, 1782–1783: Vision and Reality." International History Review (1983) 5#3 pp: 322–345. online

- ^ a b Ferling (2003), pp. 253–254

- ^ Nugent (2008), pp. 23–24

- ^ Quote from Thomas Paterson, J. Garry Clifford and Shane J. Maddock, American foreign relations: A history, to 1920 (2009) vol 1 p. 20

- ^ James W. Ely Jr. (2007). The Guardian of Every Other Right: A Constitutional History of Property Rights. Oxford UP. p. 35. ISBN 9780199724529.

- ^ Nugent (2008), pp. 13–15

- ^ a b c Ferling (2003), pp. 257–258

- ^ a b Ferling (2003), pp. 264–265

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 347

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 41–45

- ^ Maier (2010), p. 13

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 343

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 43–44

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 61–62

- ^ Nettels, Emergence of a national economy pp 45-64

- ^ Ferling (2003), p. 263

- ^ Middlekauff (2005), pp. 613–614

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates public domain material from The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. United States Department of State. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

This article incorporates public domain material from The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. United States Department of State. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ "Bastille Key". Digital Encyclopedia. Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ Hunt 1988, pp. 16–20

- ^ Hunt 1988, pp. 31–32

- ^ Hunt 1988, p. 2

- ^ Hunt 1988, pp. 30–31

- ^ Linton, Marisa (August 2006). "Robespierre and the Terror". History Today. Vol. 56, no. 8. London. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018.

- ^ "To George Washington from d'Estaing, 8 January 1784". Founders Online. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ Spalding, Paul S. (2010). Lafayette: Prisoner of State. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-911-9.

- ^ Ayer, A. J. (1988). Thomas Paine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226033392.

- ^ McDonald 1974 p.116

- ^ Smelser, Marshall (Winter 1958). "The Federalist Period as an Age of Passion". American Quarterly. 10 (4): 391–459. doi:10.2307/2710583. JSTOR 2710583.

- ^ Smelser, Marshall (1951). "The Jacobin Phrenzy: Federalism and the Menace of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity". Review of Politics. 13 (4): 457–82. doi:10.1017/s0034670500048464. S2CID 144089710.

- ^ Neuman, Simon (Winter 2000). "The World Turned Upside Down: Revolutionary Politics, Fries' and Gabriel's Rebellions, and the Fears of the Federalists". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 67 (1): 5–20.

- ^ Bowman, Albert H. (1956). "Jefferson, Hamilton and American Foreign Policy". Political Science Quarterly. 71 (1): 18–41. doi:10.2307/2144997. JSTOR 2144997.

- ^ Greg H. Williams (2009). The French Assault on American Shipping, 1793–1813: A History and Comprehensive Record of Merchant Marine Losses. McFarland. p. 14. ISBN 9780786454075.

- ^ Philip S. Foner, ed., The Democratic-Republican Societies, 1790–1800: A Documentary Sourcebook of Constitutions, Declarations, Addresses, Resolutions, and Toasts (1976).

- ^ Sheridan, Eugene R. (1994). "The Recall of Edmond Charles Genet: A Study in Transatlantic Politics and Diplomacy". Diplomatic History. 18 (4): 463–488. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1994.tb00560.x.

- ^ Gary J. Schmitt, "Washington's proclamation of neutrality: Executive energy and the paradox of executive power." Political Science Reviewer 29 (2000): 121+

- ^ Olsen, Theodore B. "Application of the Neutrality Act to Official Government Activities" (PDF). United States Justice Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ Elkins & McKitrick 1995 pp. 356, 360.

- ^ Christopher J. Young (2011). "Connecting the President and the People: Washington's Neutrality, Genet's Challenge, and Hamilton's Fight for Public Support". Journal of the Early Republic. 31 (3): 435–466. doi:10.1353/jer.2011.0040. JSTOR 41261631. S2CID 144349420.

- ^ "Genet Affair". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b c Baird, James (2002), "The Jay Treaty", The papers of John Jay, New York, New York: Columbia University Libraries, archived from the original on January 31, 2017, retrieved July 27, 2017

- ^ a b Wood 2009, p. 194

- ^ Knott, Stephen (4 October 2016). "George Washington: Foreign Affairs". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Combs 1970, p. 120

- ^ Combs 1970, p. 121

- ^ Combs 1970, p. 122

- ^ Wood 2009, p. 196

- ^ Combs 1970, p. 127

- ^ Combs 1970, p. 158

- ^ Thomas A. Bailey, A Diplomatic History of the American People (10th Ed. 1980)

- ^ Trubowitz, Peter (2011). Politics and Strategy: Partisan Ambition and American Statecraft. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-691-14957-8.

- ^ a b c d e "Jay Treaty". New York City, New York: The Lehrman Institute. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ Miller 1960, p. 149

- ^ Morison 1965, p. 344

- ^ a b Sharp 1993, pp. 113–137

- ^ a b Charles, Joseph (October 1955). "The Jay Treaty: The Origins of the American Party System". William and Mary Quarterly. 12 (4): 581–630. doi:10.2307/1918627. JSTOR 1918627.

- ^ a b Estes, Todd (2001). "The art of presidential leadership: George Washington and the Jay Treaty". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 109 (2): 127–158.

- ^ McDonald 1974 pp. 164–165

- ^ McDonald 1974 pp.169–170

- ^ Knott, Stephen (4 October 2016). "George Washington: Impact and Legacy". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Jay Treaty". Digital Encyclopedia. Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ McDonald 1974 p. 174

- ^ a b DeConde, Alexander (March 1957). "Washington's Farewell, the French Alliance, and the Election of 1796". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 43 (4): 641–658. doi:10.2307/1902277. JSTOR 1902277.

- ^ Wood 2009

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Kurtz 1957, ch. 13

- ^ Miller 1960, ch. 12

- ^ McCullough 2001, p. 495

- ^ McCullough 2001, pp. 495–496

- ^ McCullough 2001, p. 502

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 96–99

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 104–105

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 106–107

- ^ a b Ferling 1992, ch. 17

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 105–106

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 22–23

- ^ Elkins & McKitrick 1993, pp. 714–19

- ^ "John Adams I (Frigate) 1799–1867". Washington, D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command, U.S. Navy. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 141–143

- ^ Diggins 2003, pp. 118–119

- ^ Kurtz 1957, p. 331

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 112–113, 162

- ^ Brown 1975, p. 175

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 162–164

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 165–166

- ^ Diggins 2003, 145–146

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 173–174

- ^ Ferling 1992, ch. 18

- ^ Bemis, The Diplomacy Of The American Revolution (1935, 1957) pp 95-102. online

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 211–212

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 345–346

- ^ Kaplan, Colonies into Nation: American Diplomacy 1763-1801 (1972) pp 168-71.

- ^ Jane M. Berry, "The Indian Policy of Spain in the Southwest 1783-1795." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 3.4 (1917): 462-477. online

- ^ Arthur P. Whitaker, "Spain and the Cherokee Indians, 1783-98." North Carolina Historical Review 4.3 (1927): 252-269. online

- ^ Herring (2008), pp. 46–47

- ^ "Yazoo Land Fraud". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ "Papers of Thomas Carr, principle in Yazoo land fraud, digitized". UGA Libraries. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Ferling 2009, pp. 315–317

- ^ a b

This article incorporates public domain material from Treaty of San Lorenzo/ Pinckney's Treaty, 1795. United States Department of State. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

This article incorporates public domain material from Treaty of San Lorenzo/ Pinckney's Treaty, 1795. United States Department of State. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ "Pinckney's Treaty". Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ^ Young, Raymond A. (November 1963). "Pinckney's Treaty: A New Perspective". Hispanic American Historical Review. 43 (4): 526–553. doi:10.2307/2509900. JSTOR 2509900.

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 81

- ^ "Mississippi's Territorial Years: A Momentous and Contentious Affair (1798–1817) | Mississippi History Now". Missouri History Now (Missouri Historical Society). Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Brown 1975, pp. 138–148

- ^ a b c Miller 1997, pp. 33–36

- ^ a b c Fowler 1984, pp. 6–9

- ^ a b Daughan 2008, p. 242

- ^ a b Allen 1905, pp. 13–15

- ^ Daughan 2008, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Fowler 1984, pp. 16–17

- ^ Eisinger, Tom (July 12, 2015). "Pirates: An Early Test for the New Country". Pieces of History. Washington, D.C.: National Archives. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla; Roberts, Richard (September 26, 2011) [Revised and expanded version; original article by Elizabeth Huff, August 2, 2011]. "The First Barbary War". Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia. Charlottesville, Virginia: Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Allen 1909, p. 48.

Works cited[edit]

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. OCLC 1202325.

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. (2016). The First Congress. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-45169193-1.

- Brown, Ralph A. (1975). The Presidency of John Adams. American Presidency Series. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0134-1.

- Chandler, Ralph Clark (Winter 1990). "Public Administration Under the Articles of Confederation". Public Administration Quarterly. 13 (4): 433–450. JSTOR 40862257.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. City of Westminster, London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 1-59420-009-2.

- Combs, Jerald A. (1970). The Jay Treaty: Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01573-8. LCCN 70-84044.

- Daughan, George C. (2008). If By Sea: The Forging of the American Navy – From the American Revolution to the War of 1812. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01607-5. OCLC 190876973.

- Diggins, John P. (2003). Schlesinger, Arthur M. (ed.). John Adams. The American Presidents. New York, New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8050-6937-2.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1993). The Age of Federalism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195068900. OCLC 26720733.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995). The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788–1800. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509381-0.

- Ellis, Joseph (2016). "George Washington". In Gormley, Ken (ed.). The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History. New York: New York University Press Press. pp. 17–33. ISBN 9781479839902.

- Ferling, John (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0870497308. OCLC 401163336.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515924-0.

- Ferling, John (2004). Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516771-6.

- Ferling, John E. (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.

- Fowler, William M. (1984). Jack Tars and Commodores: The American Navy, 1783-1815. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35314-9. OCLC 10277756.

- Herring, George (2008). From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press.

- Hunt, Alfred N. (1988). Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ Press. ISBN 0-8071-1370-0.

- Kurtz, Stephen G. (1957). The Presidency of John Adams: The Collapse of Federalism, 1795–1800. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- McDonald, Forrest (1974). The Presidency of George Washington. American Presidency. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0359-6.

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763–1789. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, John C. (1960). The Federalist Era, 1789–1801. New York: Harper & Brothers. LCCN 60-15321 – via Universal Digital Library (2004-04-24).

- Miller, Nathan (1997). The U.S. Navy: A History (3rd ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-595-0. OCLC 37211290.

- McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press. LCCN 65-12468.

- Nugent, Walter (2008). Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansion. Knopf. ISBN 978-1400042920.

- Sharp, James Roger (1993). American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06519-1.

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions A Continental History, 1750–1804. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford History of the United States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503914-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Allen, Debra J. Historical Dictionary of U.S. Diplomacy from the Revolution to Secession (Scarecrow Press, 2012).

- Ammon, Harry. The Genet Mission. (W.W. Norton, 1971).

- Ammon, Harry. "The Genet Mission and the Development of American Political Parties." Journal of American History 52.4 (1966): 725-741. online

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. The diplomacy of the American Revolution (1935) online

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. Jay's Treaty: A Study in Commerce and Diplomacy (1923) online

- Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life (2010) online; Pulitzer Prize

- Demmer, Amanda C. "Trick or Constitutional Treaty? The Jay Treaty and the Quarrel over the Diplomatic Separation of Powers." Journal of the Early Republic 35.4 (2015): 579-598. online[dead link]

- Dobson, John M. Belligerents, Brinkmanship, and the Big Stick: A Historical Encyclopedia of American Diplomatic Concepts: A Historical Encyclopedia of American Diplomatic Concepts (ABC-CLIO, 2009) pp 1–68.

- Dull, Jonathan R. A diplomatic history of the American Revolution (Yale UP, 1987). online

- Dull, Jonathan R. Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution (2010) online

- Estes, Todd. The Jay Treaty Debate, Public Opinion, and the Evolution of Early American Political Culture (2008)

- Green, Nathaniel C. "“The Focus of the Wills of Converging Millions” Public Opposition to the Jay Treaty and the Origins of the People’s Presidency." Journal of the Early Republic 37.3 (2017): 429-469. online

- Hatter, Lawrence B. Citizens of Convenience: The Imperial Origins of American Nationhood on the US-Canadian Border (U of Virginia Press, 2016).

- Hoadley, John F. Origins of American Political Parties: 1789--1803 (University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

- Hoffman, Ronald, and Peter J. Albert, eds. Diplomacy and Revolution: The Franco-American Alliance of 1778 (1981)

- Hoffman, Ronald, and Peter J. Albert, eds. Peace and the Peacemakers: The Treaty of 1783 (1985)

- Jensen, Merrill. The New Nation: a history of the United States during the Confederation, 1781-1789 (1962) online

- Johnson, Ronald Angelo. Diplomacy in Black and White: John Adams, Toussaint Louverture, and Their Atlantic World Alliance ( University of Georgia Press, 2014).

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. Colonies into Nation: American Diplomacy, 1763-1801 (1972) online

- Ketcham, Ralph L. "France and American Politics, 1763-1793." Political Science Quarterly 78#2 (1963): 198-223. online

- Lenz, Michael. "American Fears and American Foreign Policy in the Early Republic." in Angst in den Internationalen Beziehungen 7 (2010): 151+ online.

- Morris, Richard B. The peacemakers: The great powers and American independence (1965) online

- Morris, Richard B. The forging of the Union, 1781-1789 (1987) online

- Nettels, Curtis P. The Emergence of a National Economy, 1775-1815 (1982) online, pp 1–22, 45–69, 221–238.

- Paquette, Gabriel, and Gonzalo M. Quintero Saravia, eds. Spain and the American Revolution: New Approaches and Perspectives (Routledge, 2019).

- Richmond, Gordon T. "French Support to the American Revolution: A Case Study in Unconventional Warfare" (US Army Command and General Staff College, 2019) online.

- Schroeder, Paul W. The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848 (1994).

- Schwarz, Michael. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and the British Challenge to Republican America, 1783–95 (Lexington Books, 2017).

- Scott, H. M. British Foreign Policy in the Age of the American Revolution (1990_.

- Shachtman, Tom. How the French Saved America: Soldiers, Sailors, Diplomats, Louis XVI, and the Success of a Revolution (St. Martin's Press, 2017).

- Sioli, Marco. "Citizen Genêt and Political Struggle in the Early American Republic." Revue française d'études américaines (1995): 259-267, in English.online

- Stinchcombe, William C. The American Revolution and the French Alliance (Syracuse University Press, 1969)

- Unger, Harlow Giles. The French War Against America: How a Trusted Ally Betrayed Washington and the Founding Fathers. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005). excerpt

- Van Tyne, C. H. “Influences which Determined the French Government to Make the Treaty with America, 1778.” American Historical Review 21#3 (1916): 528-541. online

Primary sources[edit]

- Giunta, Mary A., and J. Dane Hartgrove eds. Documents of the Emerging Nation: U.S. Foreign Relations, 1775-1789 (Rowman & Littlefield, 1998). online; 310pp

- Giunta, Mary A., ed. The emerging nation : a documentary history of the foreign relations of the United States under the Articles of Confederation, 1780-1789 much larger collection online; 1100 pages online

- McColley, Robert, ed. Federalists, Republicans, and foreign entanglements, 1789-1815 (1969) online , primary sources on foreign policy

- 1776 establishments in the United States

- 1801 disestablishments in the United States

- 18th century in international relations

- 1801 in international relations

- History of the foreign relations of the United States

- 1770s in the United States

- 1780s in the United States

- 1790s in the United States

- Presidency of George Washington

- Presidency of John Adams