Markwarta Street, Bydgoszcz

| Bydgoszcz | |

|---|---|

Street view westward | |

Markwarta Street highlighted on a map | |

| Native name | Ulica Księdza Ryszarda Markwarta (Polish) |

| Namesake | Father Ryszard Markwart |

| Owner | City of Bydgoszcz |

| Length | 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Width | ca. 10 m |

| Area | Downtown district |

| Location | Bydgoszcz, |

| Construction | |

| Construction start | Late 1920s[1] |

| Completion | Early 1950s |

Markwarta street is located in the downtown district of Bydgoszcz, Poland. Situated in its path are two green areas and several villas built during the Polish interwar period.

Location[edit]

East-west street track extends Krasińskiego Street to the east. It ends while meeting Ossoliński avenue and Piotrowskiego Street at Ossolińskich roundabout.

History[edit]

The axis has long been visible on Prussian maps of Bydgoszcz, mainly as an eastbound track prolonging Frönerstraße (today's Krasińskiego Street), but was never been associated with a naming.

The first city book listing Markwarta street dates back to 1928,[1] associated with the creation of the Sielanka estate (English: Idyll), set north of Markwarta street. In the 1910s, Sielanka area plans, designed as a city-garden, were drawn by German architect Josef Stübben,[2] but due to WWI the project only took off in the 1920s, hence the appearance of Markwarta street on the maps at this time.

The street is named after Ryszard Markwart (1868-1906), a Polish priest who was a nationalist activist and head of Bromberg parish from 1899 till his death.

Main edifices[edit]

Square of Lieutenant Leszek Biały

This green area is part of the Sielanka estate urban plan developed in the 1910s by German architect Josef Stübben.[3] At the time this part of the city had not been touched by urban growth, as Gdańska or Dworcowa streets could have been at the end of the 19th century. Sielanka project included this square as a property of the Province of Posen (German: Provinz Posen) and not owned by the municipality. After the rebirth of Poland in 1918, the area was declared to be constructed, but no project was ever completed. In the 1960s, a memorial has been built up to celebrate the Millennium of the Polish State (Polish: Pomnik Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego). Designed by Polish artist Stanislaw Lejkowski on July 22, 1967,[4] the entire scheme was never achieved. In 2011, the city had even projects to demolish it, but it turned out to be too expensive.[5]

The site has been given the name Lieutenant Leszek Biały in November 2013.[6] Leszek Biały was a hero of the Home Army during the Second World War. Under the code name Jakub, he was arrested in February 1945 by members of soviet controlled Ministry of Public Security and was murdered during interrogations on March 3, 1945. In October 1956, his remains were discovered in the basement of the UB building at Nr.4.[7] A renovated stone memorial to honor Leszek Biały and his heroic comrades has been unveiled in 2013.[8]

-

The square and its monument c. 1975

-

The square from the street

-

The unachieved monument to the Millennium of the Polish State

-

Detail of the crown

-

Stone memorial to Leszek Biały

Building at 2, corner with 3 Maja Street

1939[9]

The plot was purchased in 1938 by the Association of the military disabled (Polish: Związek Inwalidów Wojennych Rzeczypospolitej - ZIW) and the Association of the Blind Soldiers (Polish: Związek Ociemniałych Żołnierzy - ZOŻ) of the Republic of Poland, from a German citizen, Mr. Bohm.[9] The ground floor had a large hall and three rooms, while the upper storeys were supposed to house wounded blind soldiers and orphans children from fallen military. The opening ceremony never happened, as it was scheduled on September 3, 1939, on the first days of WII. After the war, both associations (ZIW and ZOŻ) were dissolved by the communist authorities in 1950: the edifice was transferred to the State Treasury.[9] It is still owned by the municipal council. On April 23, 1994, a commemorative plaque was placed on the building to remember its initial role.

-

View from Markwarta street

Multidisciplinary hospital at 4/6

1947[10]

The hospital was established on November 7, 1947 as a healthcare institution dedicated to Provincial Office of Public Security, Urząd Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego or UBP:[11] initially, it consisted of a building at Nr.6 and two floors of the abutting building at Nr.4 where was located Bydgoszcz UBP at the time. In the years 1966-1967, a link was built between the Nr. 4 and 6. After the expansion of the late 1980s, the hospital had 127 beds. It provided medical care for the benefit of the Ministry of Interior employees until 1990. Since the fall of communism, it provides services to all patients without any professional restrictions. Today the facility provides medical services in the field of basic health care, such as Dental and Oral Medicine, rehabilitation, occupational medicine, laboratory diagnosis and medical imaging.

The dark past of Nr.4 as UBP building has been highlighted in 2019, by the uncovering of a memorial plaque.[12]

-

View from the street

Villa at 2 Kasprowicza street, corner with Markwarta street

1927-1930,[1] by Bronisław Jankowski[3]

Polish national style

Teodor Krüger, an engineer, was the first owner of this house. He did not live there, but at Krasińskiego Street 4.[1] Today, the villa houses the Polish Foundation for the Protection of Water Resources (Polish: Izba Gospodarcza Wodociągi Polskie).

Main highlight of the edifice is the facade on Markwarta, which bears an avant-corps supported by columns, topped by a balcony fenced with a balustrade.

-

View from Markwarta street

-

View from Kasprowicza street

-

Main elevation

-

Balcony adornment

Ludowy Park

6,42 ha

1953

The park is located between the streets Jagiellońska, Piotrowski and Markwart, on a 250 by 275 m area mainly lying in the back of the Youth Palace. It was named in memoriam of Wincenty Witos.

Ludowy Park (People's Park) was founded at the place of an ancient cemetery,[13] dating back to 1778, the oldest and largest in the city.[14] In 1838 was built a house for the administrator, with a separate room for the morgue. In 1884, a cemetery was erected and in 1898 a massive brick fence, which survived after the liquidation of the cemetery.[14] Entrance was made through two wrought iron gates to Markwart street, leading to the chapel located in the middle of the graveyard. A large square with outgoing path, like spokes, divided the cemetery into quarters. A lot of different trees were growing there: oak, chestnut, European beech, downy oak, sessile oak, oak red, locust, birch, lime, common spruce, prickly spruce and white spruce, and near the house were 10 Catalpa bignonioides.[13] In 1938, 66 species of trees and shrubs were growing in the cemetery where a majority of German tombs could be found.[13]

After Bydgoszcz's liberation in 1945, the old cemetery was closed and transferred to the Lutheran cemetery in Zaświat Street.[14] The liquidation of the ancient graveyard was carried out in 1951-1952, the last bone exhumation to Zaświat street was held in 1956.[13] Many tombstones have been destroyed during the liquidation, along with sculptures, reliefs and catacombs. It has been the case for some famous people's tombstones:

- Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775-1843);

- Carl and William Blumwe, owners of Factory of Machine Tools, where a copy of the sculpture of "Christ the Saviour" by Bertel Thorvaldsen was standing. This sculpture has been moved to the square by the Lutheran Church of the Savior in Bydgoszcz, it is today one of the most impressive religious monuments in the city.

Once the cemetery liquidated, a city park, named "People's Park" (Polish: Ludowy park), has been set up on the very place, using part of the remaining elements of the gone necropolis.

In 1956, a concert shell has been erected with a capacity of 5000 people. This building replaced the amphitheatre erected in 1946 in Park Casimir the Great.[15] In addition to the concert shell, three blocks of flats on the western edge of the park, and pavilions in the east were constructed. In 1974, at the southern edge of the park has been built the "Youth Palace".[14] On June 3, 1984, at the initiative of People's Party, the park has been given the name of Wincenty Witos: his bust has been realised by Witold Marciniak and funded by Bydgoszcz Voivodeship's Polish People's Party. Between the monument and the concert shell, a round pool with a gushing summer fountain has been built.[14] In 2007 have been performed renovations of parkways, concert shell and park greenery. On April 24, 2007, a black granite obelisk commemorating the existence of the old cemetery has been unveiled in the south-east corner of the park, bearing the inscription:

City of Bydgoszcz

Lutheran Parish of Bydgoszcz

Bydgoszcz 2007"

Since 2018, a heavy revitalisation of the park is in progress, it will end in November 2019.[16]

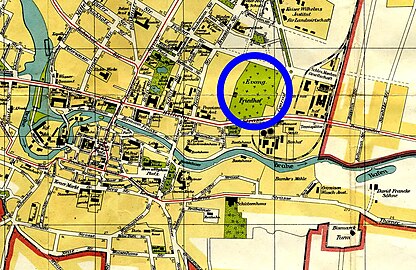

-

1914 Map of Bromberg with the Lutheran cemetery (Evang. Friedhof)

-

View of a walkway

-

View of a walkway

-

The fountain

-

Monument to Wincenty Witos

-

Commemorating obelisk

-

Bertel Thorvaldsen's sculpture, moved to Bydgoszcz's Lutheran "Church of the Savior"

Villa at 7 Markwarta street

1927-1928,[1] by Józef Grodzki[3]

First landlord was Wawrzyniec Tabaka, an engineer, who lived at 3 Królowej Jadwigi Street (Nr.8a at the time).[1] Today, the villa houses the Provincial ambulance station (Polish: Wojewódzka Stacja Pogotowia Ratunkowego).

A large avant-corps bulges forward on the main elevation, overlooked by an eyelid dormer. The villa was renovated in 2018-2019.

-

View from Markwarta street

-

Side view

-

Side view

Villa at 9 Markwarta street

1927-1929,[1] by Józef Grodzki[3]

Teoktysa Jeżewska, a retiree, is registered as first owner of the edifice in the early 1930s.[17] Warsaw-born engineer Stefan Ciszewski (1886-1938), founder of the company Eltra in 1923, lived there from 1934 till his death in 1938.[18]

The main feature of the villa is the canopied roof of the large avant-corps that juts out of the facade onto Markwarta street.

-

View from Markwarta street

-

Side view

Wacław Millner Villa at 11 Markwarta st.

1937-1938,[3] by Jan Kossowski

Wacław Milner was the owner of a mass production metal factory for bicycle, Wacław Millner or WMB, which flourished in the 1930s.[19] His plant was located at Mazowiecka street 29.[20] He had this villa realized by the famous Bydgoszcz architect Jan Kossowski in the late 1930s. Today, the building houses kinder garden N)26, Pod Tęczowym Parasolem - transl. Under the rainbow umbrella.

The edifice looks like a heavily fragmented solid, featuring many rectangle shapes, in the windows, the wide terrace or the pergola. The garden of the villa runs around the house and displays various sizes of rectangular ceramic tiles.

-

View from Markwarta street

-

Side view

-

Villa at Nr.11, with Nr.9 in the backdrop

Villa at 1 Sielanka street, corner with Markwarta street

1930-1933,[3] by Bolesław Polakiewicz

Ludwik Biały, a priest, is registered as the first owner of the villa.[17]

The house, though needing an overhaul, features typical geometrical shapes, including a massive avant-corps with a terrace on the main elevation.

-

Main elevation from Markwarta street

-

Villa at Sielanka 1, with Millner's villa in the background

Villa at 2 Sielanka street, corner with Markwarta street

1927-1928, by Bronisław Jankowski[3]

The first landlord is Mr Cacko, who did not lived in the house.[17]

The villa offers more attractive architectural details than its counterpart across Sielanka street. The modernistic body is emphasized by a large portal, flanked with two Tuscan type columns and the elevation on Markwarta street boasts a large circular avant-corps topped by a balustrade terrace.

-

View from Markwarta street

-

Round bay window

-

Main entrance

Villa at 11a Markwarta street

1970s

The villa has been erected in the 1970s, with respect to the Sielanka style which is present all around the area.

-

Main elevation from Markwarta street

-

View from the street

Buildings at 13/13a Markwarta st., 19-21 Piotrowskiego/20-22 Markwarta st.

These tenements stand at the end of Markwarta street. They have all been built in the 1930s and bear the mark of it:

- N°13/13a are located at Ossoliński Alley 1/3a;

- N°20-22 has been realized by Jan Kossowski in 1937/1938, for Józef Piecek, an engineer.[21] Modern appliances featured in the flats:[22] electric bells on the ground floor, kitchen gas stoves, a shared laundry room with a boiler and a mangle as well as a sandbox in the yard for children. Some Art deco ceramic decorations have been preserved in the entrance portals.

-

13/13a main elevation

-

Main elevation of 20 Markwarta

-

20 Piotrowskiego facade

-

Kossowski's ensemble at 19-21 Piotrowskiego/20-22 Markwarta

See also[edit]

- Bydgoszcz

- Krasińskiego street

- Staszica Street

- Ossoliński Alley in Bydgoszcz

- St. Vincent de Paul Basilica Minor in Bydgoszcz

- Piotrowskiego Street

- (in Polish) Ryszard Markwart

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Książka Adresowa Miasta Bydgoszczy : na rok 1928. Władysław Weber. 1928. p. 109.

- ^ Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji (2018). "Sielanka". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Derkowska-Kostkowska, Bogna (1999). O zalozeniu Sielanki - bydgoskiego miasta ogrodu. Materialy do dziejow kultury i sztuki bydgoszczy T4. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji zabytków Wojewódzkiego osrodja kultury w Bydgoszczy. p. 72.

- ^ "Pomnik Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Idczak, Katarzyna (2 May 2011). "Co ze skwerem na Sielance?". expressbydgoski.pl. expressbydgoski. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ kd (25 November 2013). "Tablica upamiętniająca ppor. Leszka Białego wróciła na skwer". bydgoszcz24.pl. bydgoszcz24. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Biały Leszek (1919 – 1945)". cmentarz.bydgoszcz.pl. cmentarz.bydgoszcz. 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Uroczyste odsłonięcie tablicy upamiętniającej ppor. Leszka Białego". pomorska.pl. gazeta pomorska. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Kaczmarczyk, Henryk (1995). 75 lat Związku Inwalidów Wojennych. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 157–159.

- ^ Jastrzębski, Włodzimierz (2011). Encyklopedia Bydgoszczy, t. 5. Medycyna. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. p. 125. ISBN 978-83-926423-3-6.

- ^ "Dawna siedziba WUBP i Wydziału Więziennictwa w Bydgoszczy". slady.ipn.gov.pl. Instytut Pamieci Narodowej. 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ redaktor (1 March 2019). "Tu mordowano polskich patriotów - odsłonięcie tablicy pamiątkowej". tygodnikbydgoski.pl. tygodnikbydgoski. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Kuczma, Rajmund (1995). Zieleń w dawnej Bydgoszczy. Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo".

- ^ a b c d e Gliwiński, Eugeniusz (1996). Kontrowersje wokół nazwy parku im. W. Witosa. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Pruss Zdzisław Weber Alicja, Kuczma Rajmund (2004). Bydgoski leksykon muzyczny. Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Towarzystwo Kulturalne. p. 377.

- ^ "Ruszyła rewitalizacja Parku Ludowego im W. Witosa w Bydgoszczy. Szykują się spore zmiany!". kujawskopomorskie.naszemiasto.pl. kujawskopomorskie.naszemiasto. 24 March 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Książka Adresowa Miasta Bydgoszczy: na rok 1933. Władysław Weber. 1933. pp. 44, 16, 75.

- ^ Nowastowski, Janusz (2016). "Jak w odrodzonej Bydgoszczy inż. Stefan Ciszewski tworzył polski przemysł elektrotechniczny". sep.com.pl. Stowarzyszenie Elektryków Polskich. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Anna, Tarnowska (6 June 2013). "Historia bydgoskiego przemysłu rowerowego. To były czasy". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. gazeta wyborcza. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Dawid. "Firma Emil Staide ,Wacław Millner i inne". auto-nostalgia.pl. auto-nostalgia. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Wysocka, Agnieszka (2003). Działalność architektoniczna Jana Kossowskiego w Bydgoszczy w latach 1923-1939. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 8. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. p. 93.

- ^ Spacer Modernizm po Bydgoszczy. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. 2018. pp. 1–2.

Bibliography[edit]

- (in Polish) Derkowska-Kostkowska, Bogna (1999). O zalozeniu Sielanki - bydgoskiego miasta ogrodu. Materialy do dziejow kultury i sztuki bydgoszczy T4 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji zabytków Wojewódzkiego osrodja kultury w Bydgoszczy. p. 72.

- (in Polish) Wysocka, Agnieszka (2003). Działalność architektoniczna Jana Kossowskiego w Bydgoszczy w latach 1923-1939. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 8 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. p. 93.

- (in Polish) Wysocka Agnieszka, Daria Bręczewska-Kulesza (2003). Wille na Sielance. Kronika Bydgoska Zeszyt 25 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. p. 57.

External links[edit]

- (in Polish) Association of the military disabled of the Republic of Poland

- (in Polish) Hospital at 4/6

- (in Polish) Polish Foundation for the Protection of Water Resources at 2 Kasprowicza

- (in Polish) Regional Ambulance Station at 7

- (in Polish) Kinder garden at 11