City of Ragusa

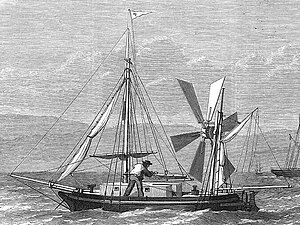

City of Ragusa at Queenstown, County Cork, 1870. The windmill was removed for the crossing.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake | Ragusa |

| Owner | Nikola Primorac (1869–1872)[1] |

| Laid down | before 1869 |

| Fate | Bombed at Liverpool Museum, 1941 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | yawl (in 19th-century terms),[2][3] ex-ship's boat |

| Tons burthen | 1.75 |

| Length | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Beam | 6 ft (1.8 m) |

| Propulsion | sail. (Windmill or hand-powered 2-bladed prop removed June 1870) |

| Sail plan | One square sail on main mast, otherwise gaff sails throughout, plus staysail and jib. |

| Complement | 2 |

| Notes | (1) Origin: Boat from brig Breeze (which foundered); (2) Drawings show British naval ensign and US flag; (3) registered Liverpool 2,020 |

City of Ragusa of Liverpool was a 20-foot (6 m) yawl (in 19th-century terms),[2][3] owned by Nikola Primorac, which twice crossed the Atlantic in the early days of 19th-century small-boat ocean-adventuring. She carried the former alternative name of Dubrovnik, the birthplace of her owner. She was originally a ship's boat of a merchantman. The 1870 east-west trip between Ireland and the United States was crewed by John Charles Buckley, a middle-aged Irishman with seagoing experience, and Primorac, a Croatian and tobacconist. The crew on the west–east return trip of 1871 were Primorac and a "lad" called Edwin Richard William Hayter from New Zealand, who had been a steward on the steamer City of Limerick of the Inman Line.

Following each trip, the ship and crew were the subject of much international public attention, and President Grant viewed the City of Ragusa after she reached America. From 1872, the ship was exhibited in various places in England including the Crystal Palace, and finally at Liverpool Museum where she was destroyed in 1941 when Liverpool was bombed. After the adventure, Primorac resumed his life as a tobacconist in Liverpool, and ultimately died in Rainhill Asylum. Hayter returned to New Zealand, and Buckley made at least one other ocean adventuring trip at the end of 1871: a cargo-ship race involving the Hypathia.

Ship[edit]

City of Ragusa[edit]

The City of Ragusa of Liverpool, no. 2,020,[4] carried the old name of Dubrovnik,[5] the city of Nikola Primorac's birth.[6] She was originally a clinker-built ship's boat. By 1870 the boat had been decked, and "yawl-rigged" (in 19th-century terms),[nb 1][2][3] which allowed "square sails on both masts, spreading altogether 70 square yards (59 m2) of canvas, in eight or nine sails."[nb 2] Before the mizzen mast was a windmill which powered a two-bladed screw propeller. Should the wind fail, the screw could be powered by hand; it could also be raised to prevent reef-damage. The same hand-worked mechanism also pumped water out of the ship. Her tanks took 100 imperial gallons (450 litres) of fresh water, and she could carry three months' victuals. At this point she was described as a ship (albeit "diminutive") by the press. She was "strongly built, double-floored inside, and [was] decked over, leaving a small cockpit aft, so that there [was] a cabin 3 ft (0.9 m) wide, and 4.5 ft (1.4 m) high from floor to roof."[2] She was double-floored and had a ballast of 3,360 lb (1,524.1 kg) of iron, a condenser for distilling drinking water from saltwater, and there was coal on board, although cooking was done with a spirit lamp.[7]

The 1870 yawl conversion (in 19th-century terms) was undertaken in Liverpool under the supervision of J.C. Buckley,[7] who received much local support in the form of victualling for the expedition.[8] The Graphic reported: "The City of Ragusa is the smallest vessel ever cleared at the Liverpool Custom House, and the gentleman who performed that duty for her also cleared the Great Eastern."[4] The ship carried the English ensign in 1870, and the US ensign in 1871.[6] Throughout the two transatlantic trips, the ship had the option for one square sail on the main mast, and all the rest would be gaff sails, plus staysail and jib. According to the Cork Daily Herald in June 1871, "She is yawl rigged, and returns to Ireland just as she left it, except that a gaff topsail is added, and that her sails have been enlarged. She bears all the traces of her long passage, being coated green with what sailors call "sea grass."[3]

In 1872, following the 1871 transatlantic crossing, the ship was exhibited at the Crystal Palace, but there was an accident. When lowering the ship to allow visitor boarding, the jackscrew holding the stern gave way, and the keel fell on Primorac's leg, causing a compound fracture. No help came. Hayter managed to lift the boat little by little, as Primorac gradually inserted wood under the keel. Primorac, bleeding profusely, was eventually taken to Guy's Hospital.[9] The ship was acquired by Mrs Simms, and was displayed at the Royal Castle Hotel, Chester Road, Tranmere, Merseyside. She then presented it to Birkenhead Park for use on the lakes. Following repairs, the ship "remained a prominent feature in the lower park for some years."[10] On 22 July 1875 "a small boat with red bottom and two top strakes painted white, name on stern City of Ragusa, Liverpool," was picked up by Captain Hewett of the schooner Success, 15 nmi (27.8 km) off Douglas Head.[11] The ship was later displayed in the Liverpool Museum, until it was destroyed by a bomb in 1941.[6][12]

Transatlantic crossings[edit]

Liverpool to Boston, 1870[edit]

On 2 June 1870 the City of Ragusa, crewed by Captain John Charles Buckley and Nikola Primorac, left Liverpool for New York.[2][13] Between Liverpool and Queenstown, County Cork they hand-wound the propeller once. The log said: "Shipped propeller and worked it by hand for six hours, and gained thereby two knots per hour."[14][15] They stopped en route between 12 and 16 June at Queenstown due to the stuffing box of the prop shaft leaking, and they probably removed the windmill gear from above decks at that point.[16][17] The trip had its share of pranks from the public. For example, on 12 June 1870, a bottle was found on the shore near Bootle. It contained a message in pencil, saying: "City of Ragusa June 4th 1870. Off the coast of Ireland making for Waterford. Captain Buckley washed overboard." The document was taken to the police office, but when the Ragusa arrived at Queenstown on 12 July the note was recognised as a forgery.[18] The ship arrived at Cork on 18 June, becoming the "centre of attraction" there.[2] Buckley did not mind the attention, but Primorac tended to lose patience, "and for all the visitors knew might have more than once consigned them to all sorts of future pains and sufferings."[16]

The Press monitored the ship's progress via reports from transatlantic vessels which spoke her at sea. For example, the Cunard SS Russia, and SS Abyssinia, spoke her on 13 August, off the Banks of Newfoundland. At that point, Primorac was introducing himself as "Antonio Romano, a native of Ragusa."[19] According to the log, on one day of the passage, the Ragusa ran 153 nmi (283.4 km); the slowest day covered 11 nmi (20.4 km).[20] They had a dog on board, but it died on 29 August.[21] They reached Boston on 8 September,[17] the 1870 Atlantic crossing having taken 92 or 98 days. "There were strong westerly winds almost from the beginning of the journey, and two or three heavy gales."[17] The Cork Constitution reported that:[16]

All things considered, she made a capital voyage across the Atlantic, and became the admiration of the nautical men of New York. No doubt was cast on the voyage of the City of Ragusa, and Captain Buckley reaped the full reward of the honours he had earned by his enterprising and extraordinary voyage. Whatever may have been the object or intent of the voyage of the tiny craft, one thing would seem certain as already published, that Capt. Buckley with his man reached the harbour of New York without aid or assistance.[16]

Ragusa suffering a "serious leakage", the crew took her to Boston for repairs first, then to New York, where she remained on exhibition over winter.[20] The ship continued to attract attention for a while, then Buckley returned to Liverpool by steamer.[16] He said "he [was] glad the journey [was] over, and, although he never had any serious doubts about being successful, he [did] not care to undertake the experiment again.[22] In 1878 Hayter wrote to The Times to say,[23]

The City of Ragusa was visited in America by President Grant and all the State officials of Boston and by the Governor and ex-Governor of Rhode Island, and was seen by Admiral Northcott and many other officers of Her Majesty's Navy and over 400,000 persons at the Crystal Palace. She ... now lies at Liverpool ... I hope next year to have her on view at my boat house [at Maidenhead]. E.R.W. Hayter.[23]

New York to Liverpool, 1871[edit]

After Buckley returned to Liverpool from New York in 1870, Primorac remained with the ship as Captain, looking for a replacement mate for the return trip to Ireland. The first potential crew member agreed to take the job on 20 May 1871, but when he saw the size of the ship he mutinied and left. A second man was offered the position, but he "refused his duty" in the same manner. Primorac then took on Edwin Hayter.[16] The Cork Daily Herald gives another view of those events:[3]

[Buckley's] retirement elevated his crew Primorez – to the position of captain, and this brave man spent the entire spring in cruising about New York and up the Hudson, and to the principal cities on that part of the coast, where extreme anxiety existed amongst the people for a glimpse at the extraordinary craft. No better idea of her apparent sea going powers could be gleaned from anything than the fact that four experienced sailors who were successively engaged to work her under the directions of Capt. Primorez, and who were anxious to give her a trial. left her on a trip up the Albany river, as they became afraid to risk their lives in her, even in the smooth inland waters.[3]

This time the Ragusa was ballasted with "a kind of new patent American brick," which Primorac wanted to exhibit at the London Exhibition.[24] At 5am on 23 May 1871 the crew let go the Sandy Hook pilot and started for Queenstown with a northerly heading.[16][25] The New York Herald called it a "foolhardy adventure," and said, "with the exception of the bark of the dog, she is probably the smallest bark that ever attempted such a trip."[26] This return trip took 36 days. The Cork Constitution reported:[16]

During the voyage the weather was rather rough, and at times squally, but the tiny craft kept on her course well, making an average in good weather seven knots, and in bad weather 4.5 knots per hour. Her best speed, and one extraordinary for so small a boat, was 160 miles on the third day after leaving her moorings. The log of her voyage could not be obtained, and many statements have been made respecting her voyage, none of which it would be safe to give as representing the whole facts. On [22 June 1871] the little craft made 120 knots during the day, which was the second-best day's running since her starting.[16]

The Illustrated Police News reported:[25]

Bad weather set in off the banks of Newfoundland, and for ten days a series of gales tossed them about in a terrific sea. The gale subsiding, the captain was able to set his vessel's head to the eastward. Icebergs were frequently seen in that latitude at that time, and a sharp look-out had to be kept. The ice was avoided, and the ship continued her course. The weather remained exceedingly heavy, and there were rare periods of calm. A succession of heavy gales came on, and as it was impossible to take observations the course was taken by dead reckoning throughout. From the beginning to the end of the passage the captain saw the sun rise and set only once, and during the remaining days the weather was too thick to permit him to make observations ... off Fastnet ... they amused themselves with catching a young shark. While following a piece of beef a noose was slipped round his tail and he was pulled on board. His tail was hung at the bowsprit, where it is still to be observed ... The captain has kept a careful log of the whole voyage, which he intends publishing.[25]

The City of Ragusa arrived at Queenstown at midnight on Wednesday 28 June 1871, "firing a gun as she entered." According to Primorac's report, he only had time to wash himself once during the voyage, but managed to change his clothes four times. He said that the pair took six-hour watches, but once during a gale Primorac did a thirty-hour watch. He added that they caught a shark near Fastnet, and indeed they arrived in harbour with what was left of the fish on board.[16] That included the jaws, teeth and backbone. The Ragusa was flying the Austrian and British flags when she arrived.[3] On 29 June "a number of people visited the little craft, and several boats laden with spectators sailed around her."[16] The Irish Daily Telegraph was one of those spectators:[27]

We saw the little thing at Queenstown, but 19 feet long, and [1.75] tons measurement, rocking to every wave of the passing stream, bending to every puff of wind, which scarcely stirred the flags of her sisters around her; we looked in wonder at her, and very few could realise that she had made two long voyages across the Atlantic; had ridden out, off the coast of Newfoundland, two severe storms; had seen large vessels dismasted, and herself surrounded with the debris, which was more dangerous to her than the contending elements. If the vessel is wonderful, the crew more so ... The owner and master, a quiet looking man, with no sign of the hero about him – with nothing to shew that patient, invincible courage, which he must possess to brave many dangers for so long a time ... The dog ... looks thoroughly miserable ... They carried no boat, nor any other means of escaping a sinking ship ... We have welcomed and admired her, and now wish her God speed.[27]

The City of Ragusa left Queenstown for Liverpool on 10 July 1871.[28]

Crew[edit]

Captain John Charles Buckley[edit]

John Charles Buckley was born in Limerick, Ireland, and had also lived in Millstreet, Cork, where he had relatives.[2] By 1870 he was "middle-aged."[22] The Illustrated London News reported in 1870:[2]

He formerly served in the army of the Papal Government and was taken prisoner, in 1860, during the short campaign of Castelfidardo and Spoleto, by the invading forces of King Victor Emmanuel. He served the Pope three years, and is a Knight of the Order of St. Sylvester. He has since been the officer of an American passenger-steamer, and lately master of a large vessel in the China trade. He has been rewarded with the honorary silver medal of the Humane Society for saving two lives on our coast near Hythe.[2]

At Trafalgar Square, London, on 12 January 1859 the Humane Society awarded J. Buckley of the Royal Limerick Militia a silver medal "for saving the lives of Sergeant M. Mahony and Private J. Bastow of the same corps ... who went to bathe in the sea, and venturing out too far would no doubt have met a watery grave, had not Buckley, after the most desperate exertions, succeeded in bringing both of them ashore."[29] The rescue occurred on 22 September 1858 at Hythe, Kent.[30]

Unlike Primorac and Hayter, Buckley did not retire from adventure. He crewed under Captain Scott on the John S.D. Wolfe sailing ship Hypathia, which left the Mersey on 18 September 1871, arriving at Philadelphia after 37 days, beating the four ships which accompanied her. Leaving Philadelphia on 4 December for Havre, she encountered "terrific westerly gales" but reached her destination after 17 days. The trip involved running before the gale, with water sweeping the decks, hands lashed at the pumps, lifelines in use, and two men at the wheel.[31]

-

Captain J.C. Buckley

-

Buckley received a Royal Humane Society silver medal in 1859

-

He received the Order of St. Sylvester from the Pope in the 1860s

Nikola Primorac[edit]

Nikola Primorac (Dubrovnik 27 July 1840 – Liverpool 1 March 1886)[2][6] (anglicised as Nicholas Primovez), otherwise known as Pietro di Costa, was a tobacconist and stationer by trade. He was Croatian, but when using the alias Pietro di Costa assumed Austrian-Italian identity. The Illustrated London News was informed that he had a wife and two children, but that they drowned as passengers on an Austrian merchant ship when it was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands, and that he was master of the ship at the time.[2][nb 3]

Primorac had a dog, Boatswain, who accompanied him on the 1871 return crossing. The dog was described by the Illustrated Police News as a "splendid brindled Bull Terrier which bore all the suffering of the long journey with as much fortitude as his fellow passengers." There were two dogs on the voyage; Hayter's Labrador was swept overboard, and Boatswain survived.[25]

However Primorac and Boatswain each came to an unfortunate end in Liverpool. On 27 December 1878, the Liverpool Mercury reported:[32]

Yesterday forenoon, the inhabitants in the neighbourhood immediately adjoining the Sailor's Home [in Duke Street, Liverpool] were rather startled by seeing a man rushing about the streets with loaded firearms, evidently intent upon shooting some one. His name was found to be Nicholas Primoraz, tobacconist and stationer, carrying on business at 56, Duke-street, and with considerable difficulty he was secured and locked up. As he is evidently out of his mind, he will be taken to a lunatic asylum. Primoraz is the man who a few years ago sailed across the Atlantic in a tiny boat named the City of Ragusa, his only companion being a dog. This dog yesterday attempted to bite a police constable who snatched a pistol from its master, and was afterwards shot with the same weapon. The faithful animal was not killed by the shot, but was afterwards drowned at the Jordan-street pinfold.[32]

According to the Liverpool Albion, Primorac was shooting at a man who in due course took over his tobacconist shop.[33] On 16 January 1879 Primorac was incarcerated in Rainhill Asylum, and on 1 March 1886 he died there.[28][34][35]

Edwin Richard William Hayter[edit]

Edwin Richard William Hayter (or sometimes Heyter) was from an expatriate English family, and was born in New Zealand.[nb 4] He had been a steward serving on the City of Limerick, a steamer of the Inman Line.[27][16] After the 1871 passage he spent some years in Maidenhead, Berkshire as a "boat owner and letter of boats on hire", then went bankrupt in 1879.[36] In 1893 he left for New Zealand, and in 1934 died there.[28] Hayter was possibly Edwin Richard Hayter (born New Zealand ca.1852), who appears in the 1891 England Census as a boot and umbrella repairer, living at 34 Water Lane, Lambeth.[37] The Cork Daily Herald said of him, "Heyter ... is a fine young man, a native of New Zealand but of English parentage, and during his time he has been almost in every part of the world."[3]

Gallery[edit]

-

City of Ragusa showing full sail, 1870. The crew are Captain J.C. Buckley and N. Primorac

-

E.R.W. Hayter (L), Captain N. Primorac (R), and Boatswain, New York, 1871

-

City of Ragusa using gaff sails only, but still with the square sail spar, 1871.

Other 19th-century, small-vessel, Atlantic crossings[edit]

- Red, White and Blue (1867): lifeboat; 26 ft LOA; 34 days.[38]

- John T. Ford (1867): capsized off Cork; 3 out of 4 crew drowned.[38][39][40][41]

- Centennial (1876) crewed by Alfred Johnson; 60 days.[38]

- The Little Western (1890): American dory of Gloucester, Massachusetts; 16 ft 7in LOA; beam 6 ft 7in; draught 6 ft 7in; 45 days.[38][42]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The term, "yawl" underwent change mid-19th century. In 1870, regarding square-rigged vessels, it could refer to something like a sloop rig, or a (former in this case) ship's boat which once had oars. Normally the mizzen would be stepped behind the tiller, but the Ragusa rig was complicated due to the position of the pump and propeller controls which remained after the windmill was removed. See Oxford Reference: Yawl

- ^ The surviving images of the ship show a spar for one square sail on the mainmast, and gaff sails on the top of the main mast and on the mizzen mast, plus staysail and jib.

- ^ No corroboration has yet been found, that Primorac had previously been master of a ship.

- ^ The Illustrated London News stated that Hayter was born in Newfoundland, but that is a misprint.

References[edit]

- ^ "Across the Atlantic in a twenty feet boat". Northern Ensign and Weekly Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 12 May 1870. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "The smallest ship of the ocean". Illustrated London News. British Newspaper Archive. 25 June 1870. p. 21 col.2. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Arrival of the City of Ragusa". Cork Daily Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 30 June 1871. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The City of Ragusa". The Graphic. British Newspaper Archive. 11 June 1870. p. 20 col.1. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Historical facts about Dubrovnik". dubrovnik-online.net. Dubrovnik Online. 18 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Eterovich, Adam; Žubrinić, Darko (18 June 2013). "Nikola Primorac Croatian captain of City of Ragusa craft sailing from Liverpool to New York and back in 1870". croatia.org. Crown, Croatian World Network. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The City of Ragusa". Cork Herald, quoted by Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 18 June 1870. p. 7 col.5. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "The City of Ragusa". Liverpool Daily Post. British Newspaper Archive. 2 June 1870. p. 9 col.2. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Shocking accident at the Crystal Palace". Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 24 July 1872. p. 5 col.6. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Lee, Robert (2018). "The challenge of managing the first publicly funded park: Edward Kemp as the "fixed" superintendent of Birkenhead Park 1843–91" (PDF). thegardenstrust.org. The Gardens Trust. p. 163. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Reports and casualties: a small boat". Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 26 July 1875. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Livepool buildings blitzed (with photo on page 4)". Liverpool Evening Express. British Newspaper Archive. 15 May 1941. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Sailing of the City of Ragusa". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 4 June 1870. p. 8 col.4. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Arrival of the City of Ragusa". Cork Examiner. British Newspaper Archive. 13 June 1870. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "The City of Ragusa". Cork Daily Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 13 June 1870. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The City of Ragusa". Cork Constitution. British Newspaper Archive. 30 June 1871. p. 2 col.6. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Title unknown". The Times. 5 October 1870.

- ^ "Messages from the sea". Shields Daily Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 1870. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Tidings of the City of Ragusa". Cork Examiner. British Newspaper Archive. 20 August 1870. p. 2 col.6. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The City of Ragusa". Shields Daily Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 23 September 1870. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "The City of Ragusa, extraordinary voyage across the Atlantic". Cork Examiner. British Newspaper Archive. 22 September 1870. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b "The voyage of the City of Ragusa". Dublin Evening Post. British Newspaper Archive. 16 November 1870. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b "A perilous voyage". Flintshire Observer. 9 August 1878. p. col..2–3. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "The City of Ragusa". No. Kilkenny Moderator. British Newspaper Archive. 5 July 1871. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Arrival of the City of Ragusa". Illustrated Police News. British Newspaper Archive. 8 July 1871. p. 3 col.6. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "A foolhardy adventure". New York Herald, quoted in Fife Free Press, & Kirkcaldy Guardian. British Newspaper Archive. 10 June 1871. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "The City of Ragusa". Irish Daily Telegraph, quoted in Cardiff Times. British Newspaper Archive. 15 July 1871. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Frecker, Paul (2020). "Nicholas Primoraz and Edwin Hayter". 19thcenturyphotos.com. The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Royal Humane Society". Morning Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 13 January 1859. p. 3 col.6. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "The Royal Humane Society". London Daily News. British Newspaper Archive. 13 January 1859. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "A fearful voyage, rapid ocean sailing". Dublin Evening Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 30 December 1871. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Sensational "scene" in Duke Street". Liverpool Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 27 December 1878. p. 6 col.6. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Extraordinary scene in Duke Street". Liverpool Albion. 27 December 1878.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 7 September 2020. Deaths Mar 1886 Primoraz Nicola 43 Prescot 8b 561

- ^ 1881 England Census: M.P. or N.P. age 38, unmarried, sailor, Rainhill Asylum, Liverpool, lunatic.

- ^ "In the County Court of Berkshire" (PDF). The London Gazette. 23 September 1879. p. 5632 col.2. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ 1891 England Census RG12/412 p.3 schedule 64

- ^ a b c d "The Little Western". Hampshire Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 4 August 1880. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "The wreck of the John T. Ford". Perthshire Constitutional & Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 5 September 1867. pp. 6–7, cols 6, 1. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Another ocean experiment". Harper's Weekly. 1 June 1867. pp. 341, 342, 349. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "The yacht John T. Ford". Richmond Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. Newspapers.com. 3 September 1867. p. 3. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "The Little Western's Voyage". New York Times. 21 August 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

Among the attractions just now at the Aquarium is the "dory" boat Little Western, in which two young American seamen, named G.P. Thomas and Frederick Norman, have just completed a risky passage across the Atlantic.

External links[edit]

- "Item No. J07.20320. City of Ragusa (yacht) crossing the Atlantic, undated". oac.cdlib.org/. Online Archive of California (OAC). Retrieved 9 September 2020. (Black and white negative captioned: "The City of Ragusa, Two Tons Burden, Now Crossing the Atlantic" (undated, but probably 1871).

- "Limerick County Militia, 1797–1846". limerick.ie. Limerick: discover. Retrieved 17 September 2020. (For further research: links to copies of Limerick militia records, which may help to identify John Charles Buckley by giving birthdate, birthplace etc.)