Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.[37][38]

According to historians and linguists, the Proto-Turkic language originated in Central-East Asia,[39] potentially in Altai-Sayan region, Mongolia or Tuva.[40][41][42] Initially, Proto-Turkic speakers were potentially both hunter-gatherers and farmers; they later became nomadic pastoralists.[43] Early and medieval Turkic groups exhibited a wide range of both East Asian and West-Eurasian physical appearances and genetic origins, in part through long-term contact with neighboring peoples such as Iranic, Mongolic, Tocharian, Uralic and Yeniseian peoples, and others.[44][45][46]

Many vastly differing ethnic groups have throughout history become part of the Turkic peoples through language shift, acculturation, conquest, intermixing, adoption, and religious conversion.[1] Nevertheless, Turkic peoples share, to varying degrees, non-linguistic characteristics like cultural traits, ancestry from a common gene pool, and historical experiences.[1] Some of the most notable modern Turkic ethnic groups include the Altai people, Azerbaijanis, Chuvash people, Gagauz people, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz people, Turkmens, Turkish people, Tuvans, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, and Yakuts.

Etymology

The first known mention of the term Turk (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 Kök Türük, Chinese: 突厥, Pinyin: Tūjué < Middle Chinese *tɦut-kyat < *dwət-kuɑt, Old Tibetan: drugu)[47][48][49][50] applied to only one Turkic group, namely, the Göktürks,[51] who were also mentioned, as türüg ~ török, in the 6th-century Khüis Tolgoi inscription, most likely not later than 587 AD.[52][53][54] A letter by Ishbara Qaghan to Emperor Wen of Sui in 585 described him as "the Great Turk Khan".[55][56] The Bugut (584 CE) and Orkhon inscriptions (735 CE) use the terms Türküt, Türk and Türük.[57]

During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the Turcae in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the Tyrcae among the people of the same area.[58][59][60] However, English archaeologist Ellis Minns contended that Tyrcae Τῦρκαι is "a false correction" for Iyrcae Ἱύρκαι, a people who dwelt beyond the Thyssagetae, according to Herodotus (Histories, iv. 22), and were likely Ugric ancestors of Magyars.[61] There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names might have been foreign transcriptions of Tür(ü)k, such as Togarma, Turukha/Turuška, Turukku and so on; but the information gap is so substantial that any connection of these ancient people to the modern Turks is not possible.[62][63]

The Chinese Book of Zhou (7th century) presents an etymology of the name Turk as derived from 'helmet', explaining that this name comes from the shape of a mountain where they worked in the Altai Mountains.[64] Hungarian scholar András Róna-Tas (1991) pointed to a Khotanese-Saka word, tturakä 'lid', semantically stretchable to 'helmet', as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data.[65]

It is generally accepted that the name Türk is ultimately derived from the Old-Turkic migration-term[66] 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük/Törük,<[67] which means 'created, born'[68] or 'strong'.[69] Turkologist Peter B. Golden agrees that the term Turk has roots in Old Turkic,[70] yet is not convinced by attempts to link Dili, Dingling, Chile, Tele, and Tiele, which possibly transcribed *tegrek (probably meaning 'cart'), to Tujue, which transliterated to Türküt.[71]

Scholars, including Toru Haneda, Onogawa Hidemi, and Geng Shimin believed that Di, Dili, Dingling, Chile and Tujue all came from the Turkic word Türk, which means 'powerful' and 'strength', and its plural form is Türküt.[72] Even though Gerhard Doerfer supports the proposal that türk means 'strong' in general, Gerard Clauson points out that "the word türk is never used in the generalized sense of 'strong'" and that türk was originally a noun and meant "'the culminating point of maturity' (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an [adjective] meaning (of a fruit) 'just fully ripe'; (of a human being) 'in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'".[73] Hakan Aydemir (2022) also contends that Türk originally did not mean "strong, powerful" but "gathered; united, allied, confederated" and was derived from Pre-Proto-Turkic verb *türü "heap up, collect, gather, assemble".[74]

The earliest Turkic-speaking peoples identifiable in Chinese sources are the Yenisei Kyrgyz and Xinli, located in South Siberia.[75][76][note 2] Another example of an early Turkic population would be the Dingling.[81][82][83]

In Late Antiquity itself, as well as in and the Middle Ages, the name "Scythians" was used in Greco-Roman and Byzantine literature for various groups of nomadic "barbarians" living on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe who were not related to the actual Scythians.[84][85] Medieval European chroniclers subsumed various Turkic peoples of the Eurasian steppe as "Scythians". Between 400 CE and the 16th century, Byzantine sources use the name Σκύθαι (Skuthai) in reference to twelve different Turkic peoples.[86]

In the modern Turkish language as used in the Republic of Turkey, a distinction is made between "Turks" and the "Turkic peoples" in loosely speaking: the term Türk corresponds specifically to the "Turkish-speaking" people (in this context, "Turkish-speaking" is considered the same as "Turkic-speaking"), while the term Türki refers generally to the people of modern "Turkic Republics" (Türki Cumhuriyetler or Türk Cumhuriyetleri). However, the proper usage of the term is based on the linguistic classification in order to avoid any political sense. In short, the term Türki can be used for Türk or vice versa.[87]

List of ethnic groups

- Historical Turkic groups

- Az

- Dingling

- Bulgars

- Esegel

- Barsils

- Alat

- Basmyl

- Onogurs

- Saragurs

- Sabirs

- Shatuo

- Ongud (from Shatuo)

- Göktürks

- Oghuz Turks

- Kanglys

- Khazars

- Kipchaks

- Kurykans

- Kumans

- Pechenegs

- Karluks

- Tiele

- Turgesh

- Tukhsi

- Yenisei Kirghiz

- Chigils

- Toquz Oghuz

- Orkhon Uyghurs

- Yagma

- Nushibi

- Duolu

- Kutrigurs

- Utigurs

- Yabaku

- Yueban[note 3]

- Bulaqs

- Xueyantuo

- Torks

- Chorni Klobuky

- Berendei

- Yemeks

- Karamanlides (partly)[88][89]

- Naimans (partly)

- Keraites (partly)

- Merkits (partly)[note 4]

- Uriankhai (partly)[note 5]

Possible Proto-Turkic ancestry, at least partial,[90][91][92][93][94][95] has been posited for Xiongnu, Huns and Pannonian Avars, as well as Tuoba and Rouran, who were of Proto-Mongolic Donghu ancestry.[96][97][98][99] as well as Tatars, Rourans' supposed descendants.[100][101][note 6]

Remarks

- ^ Figure combines population of Turkmen and Uzbeks only. Population estimates of Turkmenistan's minority groups often widely vary. Some sources have cast doubt on the reliability of official government data for minority population figures.[17][18]

- ^ The Xueyantuo were first known as Xinli 薪犁, later Xue 薛 in the 7th century;[77][78] the Yenisei Kyrgyz were first known as Gekun (鬲昆) or Jiankun (堅昆), later known as Jiegu (結骨), Hegu (紇骨), Hegusi (紇扢斯), Hejiasi (紇戛斯), Hugu (護骨), Qigu (契骨), Juwu (居勿), and Xiajiasi (黠戛斯), all being transcriptions of Kyrgyz.[79][80]

- ^ Book of Wei vol. 102. quote: "悅般國 [...] 其風俗言語與高車同" translation: "Yueban nation [...] Their customs and language are the same as the Gaoche['s]"; Gaoche (高車; lit. "High-Carts") was another name of the Turkic-speaking Tiele

- ^ Merkits were always counted as a part of the Mongols within the Mongol Empire, however, some scholars proposed additional Turkic ancestry for Merkits; Christopher P. Atwood – Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3, Facts on File, Inc. 2004.

- ^ Refers to forest peoples of the North, including the Turkic-speaking Tuvans and Yakuts, and also Mongolic-speaking Altai Uriankhai. The ethnonym Uriankhai is etymologically Mongolic, compare Khalkha uria(n) "war motto" and khai, alternation of khan. Uriankhai people are possibly linked to the Wuluohun tribe of the Shiwei people, who were predominantly Mongolic-speaking.

- ^ Even though Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origin to various nomadic peoples, such ascriptions do not necessarily indicate the subjects' exact origins; for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitan.[102]

Language

Distribution

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of some 30 languages, spoken across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, to Siberia and Manchuria and through to the Middle East. Some 170 million people have a Turkic language as their native language;[103] an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers.[104] More than one third of these are ethnic Turks of Turkey, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman-dominated areas of Southern and Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic people are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, and northern Iraq.

The Turkic language family is traditionally considered to be part of the proposed Altaic language family.[105] Howeover since the 1950s, many comparative linguists have rejected the proposal, after supposed cognates were found not to be valid, hypothesized sound shifts were not found, and Turkic and Mongolic languages were found to be converging rather than diverging over the centuries. Opponents of the theory proposed that the similarities are due to mutual linguistic influences between the groups concerned.[106][107][108][109][110]

Alphabet

The Turkic alphabets are sets of related alphabets with letters (formerly known as runes), used for writing mostly Turkic languages. Inscriptions in Turkic alphabets were found in Mongolia. Most of the preserved inscriptions were dated to between 8th and 10th centuries CE.

The earliest positively dated and read Turkic inscriptions date from the 8th century, and the alphabets were generally replaced by the Old Uyghur alphabet in the East and Central Asia, Arabic script in the Middle and Western Asia, Cyrillic in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, and Latin alphabet in Central Europe. The latest recorded use of Turkic alphabet was recorded in Central Europe's Hungary in 1699 CE.

The Turkic runiform scripts, unlike other typologically close scripts of the world, do not have a uniform palaeography as do, for example, the Gothic runiform scripts, noted for their exceptional uniformity of language and paleography.[111] The Turkic alphabets are divided into four groups, the best known of which is the Orkhon version of the Enisei group. The Orkhon script is the alphabet used by the Göktürks from the 8th century to record the Old Turkic language. It was later used by the Uyghur Empire; a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Kyrgyz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian script of the 10th century. Irk Bitig is the only known complete manuscript text written in the Old Turkic script.[112]

History

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

Origins

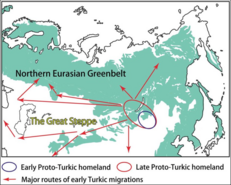

The origins of the Turkic peoples has been a topic of much discussion.[113][114] Peter Benjamin Golden proposes two locations for the Proto-Turkic Urheimat: the southern Altai-Sayan region,[40] and in Southern Siberia, from Lake Baikal to eastern Mongolia.[115] Other studies suggested an early presence of Turkic peoples in Mongolia,[116][41] or Tuva.[42]

A possible genealogical link of the Turkic languages to Mongolic and Tungusic languages, specifically a hypothetical homeland in Manchuria, such as proposed in the Transeurasian hypothesis, by Martine Robbeets, has received support but also criticism, with opponents attributing similarities to long-term contact.[117][118][119] The proto-Turkic-speakers may be linked to Neolithic East Asian agricultural societies in Northeastern China, which is to be associated with the Xinglongwa culture and the succeeding Hongshan culture, based on varying degrees of specific East Asian genetic substratum among modern Turkic speakers.[120][121][122] According to historians, "the Proto-Turkic subsistence strategy included an agricultural component, a tradition that ultimately went back to the origin of millet agriculture in Northeast China".[120][121][122] This view is however questioned by other geneticists, who found no evidence for a shared "Neolithic Hongshan ancestry", but in contrary primary Ancient Northeast Asian (ANA) Neolithic ancestry from the Amur region, supporting an origin from Northeast Asia rather than Manchuria.[123]

Around 2,200 BC, the (agricultural) ancestors of the Turkic peoples probably migrated westwards into Mongolia, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle, in part borrowed from Iranian peoples. Given nomadic peoples such as Xiongnu, Rouran and Xianbei share underlying genetic ancestry "that falls into or close to the northeast Asian gene pool", the proto-Turkic language likely originated in northeastern Asia.[125]

Genetic data found that almost all modern Turkic peoples retained at least some shared ancestry associated with populations in "South Siberia and Mongolia" (SSM), supporting this region as the "Inner Asian Homeland (IAH) of the pioneer carriers of Turkic languages" which subsequently expanded into Central Asia. The main Turkic expansion took place during the 5th–16th centuries, partially overlapping with the Mongol Empire period. Based on single-path IBD tracts, the common Turkic ancestral population lived prior to these migration events, and likely stem from a similar source population as Mongolic peoples further East. Historical data suggests that the Mongol Empire period acted as secondary force of "turkification", as the Mongol conquest "did not involve massive re-settlements of Mongols over the conquered territories. Instead, the Mongol war machine was progressively augmented by various Turkic tribes as they expanded, and in this way Turkic peoples eventually reinforced their expansion over the Eurasian steppe and beyond."[114]

A 2018 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphism study suggested that the Eurasian Steppe slowly transitioned from Indo European and Iranian-speaking groups with largely western Eurasian ancestry to increasing East Asian ancestry with Turkic and Mongolian groups in the past 4000 years, including extensive Turkic migrations out of Mongolia and slow assimilation of local populations.[126][122] A 2022 suggested that Turkic and Mongolic populations in Central Asia formed via admixture events during the Iron Age between "local Indo-Iranian and a South-Siberian or Mongolian group with a high East-Asian ancestry (around 60%)." Modern day Turkmens form an outlier among Central Asian Turkic-speakers with a lower frequency of the Baikal component (c. 22%) and a lack of the Han-like component, being closer to other Indo-Iranian groups.[127] A subsequent study in 2022 also found that the spread of Turkic-speaking populations into Central Asia happened after the spread of Indo-European speakers into the area.[128] Another 2022 study found that all Altaic‐speaking (Turkic , Tungusic, and Mongolic) populations "were a mixture of dominant Siberian Neolithic ancestry and non-negligible YRB ancestry", suggesting their origins were somewhere in Northeast Asia, most likely the Amur river basin. Except Eastern and Southern Mongolic-speakers, all "possessed a high proportion of West Eurasian-related ancestry, in accordance with the linguistically documented language borrowing in Turkic languages".[123]

A 2023 study analyzed the DNA of Empress Ashina (568–578 AD), a Royal Göktürk, whose remains were recovered from a mausoleum in Xianyang, China.[129] The authors determined that Empress Ashina belonged to the North-East Asian mtDNA haplogroup F1d, and that approximately 96-98% of her autosomal ancestry was of Ancient Northeast Asian origin, while roughly 2-4% was of West Eurasian origin, indicating ancient admixture.[129] This study weakened the "western Eurasian origin and multiple origin hypotheses".[129] However, they also noted that "Central Steppe and early Medieval Türk exhibited a high but variable degree of West Eurasian ancestry, indicating there was a genetic substructure of the Türkic empire."[129] The early medieval Türk samples were modelled as having 37.8% West Eurasian ancestry and 62.2% Ancient Northeast Asian ancestry[130] and historic Central Steppe Türk samples were also an admixture of West Eurasian and Ancient Northeast Asian ancestry,[131] while historic Karakhanid, Kipchak and the Turkic Karluk samples had 50.6%-61.1% West Eurasian ancestry and 38.9%–49.4% Iron Age Yellow River farmer ancestry.[132] A 2020 study also found "high genetic heterogeneity and diversity during the Türkic and Uyghur periods" in the early medieval period in Eastern Eurasian Steppe.[133]

Early historical attestation

The earliest separate Turkic peoples, such as the Gekun (鬲昆) and Xinli (薪犁), appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BCE[134][135] (contemporaneous with the Chinese Han Dynasty)[136] and later among the Turkic-speaking Tiele[137] as Hegu (紇骨)[138] and Xue (薛).[77][78]

The Tiele (also known as Gaoche 高車, lit. "High Carts"),[139] may be related to the Xiongnu and the Dingling.[140] According to the Book of Wei, the Tiele people were the remnants of the Chidi (赤狄), the red Di people competing with the Jin in the Spring and Autumn period.[141] Historically they were established after the 6th century BCE.[135]

The Tiele were first mentioned in Chinese literature from the 6th to 8th centuries.[142] Some scholars (Haneda, Onogawa, Geng, etc.) proposed that Tiele, Dili, Dingling, Chile, Tele, & Tujue all transliterated underlying Türk; however, Golden proposed that Dili, Dingling, Chile, Tele, & Tiele transliterated Tegrek while Tujue transliterated Türküt, plural of Türk.[143] The appellation Türük (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰) ~ Türk (OT: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚) (whence Middle Chinese 突厥 *dwət-kuɑt > *tɦut-kyat > standard Chinese: Tūjué) was initially reserved exclusively for the Göktürks by Chinese, Tibetans, and even the Turkic-speaking Uyghurs. In contrast, medieval Muslim writers, including Turkic speakers like Ottoman historian Mustafa Âlî and explorer Evliya Çelebi as well as Timurid scientist Ulugh Beg, often viewed Inner Asian tribes, "as forming a single entity regardless of their linguistic affiliation" commonly used Turk as a generic name for Inner Asians (whether Turkic- or Mongolic-speaking). Only in modern era do modern historians use Turks to refer to all peoples speaking Turkic languages, differentiated from non-Turkic speakers.[144]

According to some researchers (Duan, Xue, Tang, Lung, Onogawa, etc.) the later Ashina tribe descended from the Tiele confederation.[145][146][147][148][149] The Tiele however were probably one of many early Turkic groups, ancestral to later Turkic populations.[150][151] However, according to Lee & Kuang (2017), Chinese histories do not describe the Ashina and the Göktürks as descending from the Dingling or the Tiele confederation.[152]

Xiongnu (3rd c. BCE – 1st c. CE)

It has even been suggested that the Xiongnu themselves, who were mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic speakers.[153][154][155][156] The Turks may ultimately have been of Xiongnu descent.[157] Although little is known for certain about the Xiongnu language(s), it seems likely that at least a considerable part of Xiongnu tribes spoke a Turkic language.[158] Some scholars believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups.[159][160] According to a study by Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong, published in 2020 in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences by Cambridge University Press, "the predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic". However, genetic studies found a mixture of western and eastern Eurasian ancestries, suggesting a large genetic diversity within the Xiongnu. The Turkic-related component may be brought by eastern Eurasian genetic substratum.[161]

Using the only extant possibly Xiongnu writings, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helan Mountains,[162] some scholars argue that the older Xiongnu writings are precursors to the earliest known Turkic alphabet, the Orkhon script. Petroglyphs of this region dates from the 9th millennium BCE to the 19th century, and consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and few painted images.[163] Excavations done during 1924–1925 in Noin-Ula kurgans located in the Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulaanbaatar produced objects with over 20 carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.[164]

Huns (4th–6th c. CE)

In the 18th century, the French scholar Joseph de Guignes became the first to propose a link between the Huns and the Xiongnu people, who were northern neighbours of China in the 3rd century BC.[165] The Hun hordes ruled by Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century, might have been, at least partially, Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.[136][166][167] Since Guignes' time, considerable scholarly effort has been devoted to investigating such a connection. The issue remains controversial. Their relationship to other peoples known collectively as the Iranian Huns is generally accepted, but whether these groups are all inter-related remains controversial.[168]

Some scholars claimed Huns as Proto-Mongolian or Yeniseian in origin.[169][170] Linguistic studies by Otto Maenchen-Helfen and others have suggested that the language used by the Huns in Europe was too little documented to be classified. Nevertheless, the majority of the proper names used by Huns appear to be Turkic in origin,[171][172] though they are "far from unambiguous, so no firm conclusion can be drawn from this type of data".[173]

Steppe expansions

Göktürks – Turkic Khaganate (5th–8th c.)

The earliest certain mentioning of the politonym "Turk" was in the Chinese Book of Zhou. In the 540s AD, this text mentions that the Turks came to China's border seeking silk goods and a trade relationship. A Sogdian diplomat represented China in a series of embassies between the Western Wei dynasty and the Turks in the years 545 and 546.[175]

According to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed barbarians" (雜胡; záhú) who migrated from Pingliang (now in modern Gansu province, China) to the Rourans seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from the prevailing dynasty.[176][177] Alternatively, according to the Book of Zhou, History of the Northern Dynasties, and New Book of Tang, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation.[178][179][180][181] Göktürks were also posited as having originated from an obscure Suo state (索國), north of the Xiongnu.[182][183] The Ashina tribe were famed metalsmiths and were granted land south of the Altai Mountains (金山 Jinshan), which looked like a helmet, from which they were said to have gotten their name 突厥 (Tūjué),[184][176] the first recorded use of "Turk" as a political name. In the 6th-century, Ashina's power had increased such that they conquered the Tiele on their Rouran overlords' behalf and even overthrew Rourans and established the First Turkic Khaganate.[185]

The original Old Turkic name Kök Türk derives from kök ~ kö:k, "sky, sky-coloured, blue, blue-grey".[186] Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khaganate had its temporary Khagans from the Ashina clan, who were subordinate to a sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khaganate retained elements of its original animistic- shamanistic religion, that later evolved into Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khaganate was also the first state known as "Turk". It eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but many states and peoples later used the name "Turk".[187][188]

The Göktürks (First Turkic Kaganate) quickly spread west to the Caspian Sea. Between 581 and 603 the Western Turkic Khaganate in Kazakhstan separated from the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in Mongolia and Manchuria during a civil war. The Han-Chinese successfully overthrew the Eastern Turks in 630 and created a military Protectorate until 682. After that time the Second Turkic Khaganate ruled large parts of the former Göktürk area. After several wars between Turks, Chinese and Tibetans, the weakened Second Turkic Khaganate was replaced by the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 744.[189]

Bulgars, Golden Horde and the Siberian Khanate

The Bulgars established themselves in between the Caspian and Black Seas in the 5th and 6th centuries, followed by their conquerors, the Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th or 9th century. After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks. One group of Bulgars settled in the Volga region and mixed with local Volga Finns to become the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan. These Bulgars were conquered by the Mongols following their westward sweep under Ogedei Khan in the 13th century.[190] Other Bulgars settled in Southeastern Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and mixed with the Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.[185]

The Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 922 and influenced the region as it controlled many trade routes. In the 13th century, Mongols invaded Europe and established the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, western & northern Central Asia, and even western Siberia. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation and Islamic Volga Bulgaria were absorbed by the Golden Horde in the 13th century; in the 14th century, Islam became the official religion under Uzbeg Khan where the general population (Turks) as well as the aristocracy (Mongols) came to speak the Kipchak language and were collectively known as "Tatars" by Russians and Westerners. This country was also known as the Kipchak Khanate and covered most of what is today Ukraine, as well as the entirety of modern-day southern and eastern Russia (the European section). The Golden Horde disintegrated into several khanates and hordes in the 15th and 16th century including the Crimean Khanate, Khanate of Kazan, and Kazakh Khanate (among others), which were one by one conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th through 19th centuries.[191]

In Siberia, the Siberian Khanate was established in the 1490s by fleeing Tatar aristocrats of the disintegrating Golden Horde who established Islam as the official religion in western Siberia over the partly Islamized native Siberian Tatars and indigenous Uralic peoples. It was the northernmost Islamic state in recorded history and it survived up until 1598 when it was conquered by Russia.[192]

Uyghur Khaganate (8th–9th c.)

The Uyghur Khaganate had established itself by the year 744 AD.[193] Through trade relations established with China, its capital city of Ordu Baliq in central Mongolia's Orkhon Valley became a wealthy center of commerce,[194] and a significant portion of the Uyghur population abandoned their nomadic lifestyle for a sedentary one. The Uyghur Khaganate produced extensive literature, and a relatively high number of its inhabitants were literate.[195]

The official state religion of the early Uyghur Khaganate was Manichaeism, which was introduced through the conversion of Bögü Qaghan by the Sogdians after the An Lushan rebellion.[196] The Uyghur Khaganate was tolerant of religious diversity and practiced variety of religions including Buddhism, Christianity, shamanism and Manichaeism.[197]

During the same time period, the Shatuo Turks emerged as power factor in Northern and Central China and were recognized by the Tang Empire as allied power.

In 808, 30,000 Shatuo under Zhuye Jinzhong defected from the Tibetans to Tang China and the Tibetans punished them by killing Zhuye Jinzhong as they were chasing them.[198] The Uyghurs also fought against an alliance of Shatuo and Tibetans at Beshbalik.[199]

The Shatuo Turks under Zhuye Chixin (Li Guochang) served the Tang dynasty in fighting against their fellow Turkic people in the Uyghur Khaganate. In 839, when the Uyghur khaganate (Huigu) general Jueluowu (掘羅勿) rose against the rule of then-reigning Zhangxin Khan, he elicited the help from Zhuye Chixin by giving Zhuye 300 horses, and together, they defeated Zhangxin Khan, who then committed suicide, precipitating the subsequent collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate. In the next few years, when Uyghur Khaganate remnants tried to raid Tang borders, the Shatuo participated extensively in counterattacking the Uyghur Khaganate with other tribes loyal to Tang.[200] In 843, Zhuye Chixin, under the command of the Han Chinese officer Shi Xiong with Tuyuhun, Tangut and Han Chinese troops, participated in a raid against the Uyghur khaganate that led to the slaughter of Uyghur forces at Shahu mountain.[201][202][203]

The Shatuo Turks had founded several short-lived sinicized dynasties in northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period starting with Later Tang. The Shatuo chief Zhuye Chixin's family was adopted by the Tang dynasty and given the title prince of Jin and the Tang dynasty imperial surname of Li, which is why the Shatuo of Later Tang claimed to be restoring the Tang dynasty and not founding a new one. The official language of these dynasties was Chinese and they used Chinese titles and names. Some Shaotuo Turk emperors (of the Later Jin, Later Han and Northern Han) also claimed patrilineal Han Chinese ancestry.[204][205][206]

After the fall of the Tang-Dynasty in 907, the Shatuo Turks replaced them and created the Later Tang Dynasty in 923. The Shatuo Turks ruled over a large part of northern China, including Beijing. They adopted Chinese names and united Turkic and Chinese traditions. Later Tang fell in 937 but the Shatuo rose to become a powerful faction of northern China. They created two other dynasties, including the Later Jin and Later Han and Northern Han (Later Han and Northern Han were ruled by the same family, with the latter being a rump state of the former). The Shatuo Liu Zhiyuan was a Buddhist and he worshipped the Mengshan Giant Buddha in 945. The Shatuo dynasties were replaced by the Han Chinese Song dynasty.[207][208] The Shatuo became the Ongud Turks living in Inner Mongolia after the Song dynasty conquered the last Shatuo dynasty of Northern Han.[209][210] The Ongud assimilated to the Mongols.[211][212][213][210]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz allied with China to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in the year 840 AD.[189][207] From the Yenisei River, the Kyrgyz pushed south and eastward in to Xinjiang and the Orkhon Valley in central Mongolia, leaving much of the Uyghur civilization in ruins.[214] Much of the Uyghur population relocated to the southwest of Mongolia, establishing the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in Gansu where their descendants are the modern day Yugurs and Qocho Kingdom in Turpan, Xinjiang.[215]

Central Asia

Kangar union (659–750)

The Kangar Union (Qanghar Odaghu) was a Turkic state in the former territory of the Western Turkic Khaganate (the entire present-day state of Kazakhstan, without Zhetysu). The capital of the Kangar union was located in the Ulytau mountains. Among the Pechenegs, the Kangar[note 1] formed the elite of the Pecheneg tribes. After being defeated by the Kipchaks, Oghuz Turks, and the Khazars, they migrated west and defeated Magyars,[216] and after forming an alliance with the Bulgars, they defeated the Byzantine Army.[217] The Pecheneg state was established by the 11th century and at its peak carried a population of over 2.5 million, composed of many different ethnic groups.[218]

The elite of the Kangar tribes are believed to have had an Iranian origin,[219] and they likely spoke an Iranian language,[220] while most of the Pecheneg population spoke a Turkic language, with a significant percentage speaking Hunno-Bulgar dialects.

The Yatuks, a tribe within the Kangar state who could not accompany the Kangars as they migrated West, remained in the old lands, where they are known as the Kangly people, who are now part of the Uzbek, Kazakh, and Karakalpak tribes.[221]

Oghuz Yabgu State (766–1055)

The Oguz Yabgu State (Oguz il, meaning "Oguz Land", "Oguz Country")(750–1055) was a Turkic state, founded by Oghuz Turks in 766, located geographically in an area between the coasts of the Caspian and Aral Seas. Oguz tribes occupied a vast territory in Kazakhstan along the Irgiz, Yaik, Emba, and Uil rivers, the Aral Sea area, the Syr Darya valley, the foothills of the Karatau Mountains in Tien-Shan, and the Chui River valley (see map). The Oguz political association developed in the 9th and 10th centuries in the Syr Darya basin.[222]

Salar Oghuz migration

The Salars are desended from Turkmen who migrated from Central Asia and settled in a Tibetan area of Qinghai under Ming Chinese rule. The Salar ethnicity formed and underwent ethnogenesis from a process of male Turkmen migrants from Central Asia marrying Amdo Tibetan women during the early Ming dynasty.[223][224][225][226]

Iranian, Indian, Arabic, and Anatolian expansion

Turkic peoples and related groups migrated west from present-day Northeastern China, Mongolia, Siberia and the Turkestan-region towards the Iranian plateau, South Asia, and Anatolia (modern Turkey) in many waves. The date of the initial expansion remains unknown.

Persia

The Ghaznavid dynasty (Persian: غزنویان ġaznaviyān) was a Persianate[227] Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin,[228] at their greatest extent ruling large parts of Iran, Afghanistan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest Indian subcontinent (part of Pakistan) from 977 to 1186.[229][230][231] The dynasty was founded by Sabuktigin upon his succession to rule of the region of Ghazna after the death of his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, who was a breakaway ex-general of the Samanid Empire from Balkh, north of the Hindu Kush in Greater Khorasan.[232]

Although the dynasty was of Central Asian Turkic origin, it was thoroughly Persianised in terms of language, culture, literature and habits[233][234][235][236] and hence is regarded by some as a "Persian dynasty".[237]

Seljuk Empire (1037–1194)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

The Seljuk Empire (Persian: آل سلجوق, romanized: Āl-e Saljuq, lit. 'House of Saljuq') or the Great Seljuq Empire[238][239][240] was a high medieval Turko-Persian[241] Sunni Muslim empire, originating from the Qiniq branch of Oghuz Turks.[242] At its greatest extent, the Seljuk Empire controlled a vast area stretching from western Anatolia and the Levant to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf in the south.

The Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016–1063) and his brother Chaghri Beg (989–1060) in 1037. From their homelands near the Aral Sea, the Seljuks advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia, before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia. Here the Seljuks won the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and conquered most of Anatolia from the Byzantine Empire, which became one of the reasons for the first crusade (1095–1099). From c. 1150–1250, the Seljuk empire declined, and was invaded by the Mongols around 1260. The Mongols divided Anatolia into emirates. Eventually one of these, the Ottoman, would conquer the rest.[243]

Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

The Timurid Empire was a Turko-Mongol empire founded in the late 14th century through military conquests led by Timurlane. The establishment of a cosmopolitan empire was followed by the Timurid Renaissance, a period of local enrichment in mathematics, astronomy, architecture, as well as newfound economic growth.[244] The cultural progress of the Timurid period ended as soon as the empire collapsed in the early 16th century, leaving many intellecuals and artists to turn elsewhere in search of employment.[245]

Central Asian khanates (1501–1920)

The Bukhara Khanate was an Uzbek[246] state that existed from 1501 to 1785. The khanate was ruled by three dynasties of the Shaybanids, Janids and the Uzbek dynasty of Mangits. In 1785, Shahmurad, formalized the family's dynastic rule (Manghit dynasty), and the khanate became the Emirate of Bukhara (1785–1920).[247] In 1710, the Kokand Khanate (1710–1876) separated from the Bukhara Khanate. In 1511–1920, Khwarazm (Khiva Khanate) was ruled by the Arabshahid dynasty and the Uzbek dynasty of Kungrats.[248]

Afsharid dynasty (1736–1796)

The Afsharid dynasty was named after the Turkic Afshar tribe to which they belonged. The Afshars had migrated from Turkestan to Azerbaijan in the 13th century. The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the military commander Nader Shah who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself King of Iran. Nader belonged to the Qereqlu branch of the Afshars.[249] During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sassanid Empire.

Qajar dynasty (1789–1925)

The Qajar dynasty was created by the Turkic Qajar tribe, ruling over Iran from 1789 to 1925.[250][251] The Qajar family took full control of Iran in 1794, deposing Lotf 'Ali Khan, the last Shah of the Zand dynasty, and re-asserted Iranian sovereignty over large parts of the Caucasus. In 1796, Mohammad Khan Qajar seized Mashhad with ease,[252] putting an end to the Afsharid dynasty, and Mohammad Khan was formally crowned as Shah after his punitive campaign against Iran's Georgian subjects.[253] In the Caucasus, the Qajar dynasty permanently lost many of Iran's integral areas[254] to the Russians over the course of the 19th century, comprising modern-day Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan and Armenia.[255] The dynasty was founded by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar and continued until Ahmad Shah Qajar.

South Asia

The Delhi Sultanate is a term used to cover five short-lived, Delhi-based kingdoms, two of which were of Turkic origins: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90) and the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414). Southern India saw rise of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, one of the Deccan sultanates. The Mughal Empire was a Turko-Mongol empire that, at its greatest territorial extent, ruled most of South Asia, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and parts of Uzbekistan from the early 16th to the early 18th centuries. The Mughal dynasty was founded by a Turko-Mongol prince named Babur (reigned 1526–30), who was descended from Timur (Tamerlane) on his father's side and from Chagatai, second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother's side.[256][257] A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state.[256][258][259][260]

Arab world

The Arab Muslim Umayyads and Abbasids fought against the pagan Turks in the Türgesh Khaganate in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the 10th century. Examples of regional de facto independent states include the short lived Tulunids and Ikhshidids in Egypt. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.[185]

Anatolia – Ottomans

After many battles, the western Oghuz Turks established their own state and later constructed the Ottoman Empire. The main migration of the Oghuz Turks occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East.[185] They also took part in the military encounters of the Crusades.[261] In 1090–91, the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army.[262]

As the Seljuk Empire declined following the Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire emerged as the new important Turkic state, that came to dominate not only the Middle East, but even southeastern Europe, parts of southwestern Russia, and northern Africa.[185]

Islamization

Turkic peoples like the Karluks (mainly 8th century), Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Turkmens, and Kipchaks later came into contact with Muslims, and most of them gradually adopted Islam. Some groups of Turkic people practice other religions, including their original animistic-shamanistic religion, Christianity, Burkhanism, Judaism (Khazars, Krymchaks, Crimean Karaites), Buddhism, and a small number of Zoroastrians.

Modern history

The Ottoman Empire gradually grew weaker in the face of poor administration, repeated wars with Russia, Austria and Hungary, and the emergence of nationalist movements in the Balkans, and it finally gave way after World War I to the present-day Republic of Turkey.[185] Ethnic nationalism also developed in Ottoman Empire during the 19th century, taking the form of Pan-Turkism or Turanism.

The Turkic peoples of Central Asia were not organized in nation-states during most of the 20th century, after the collapse of the Russian Empire living either in the Soviet Union or (after a short-lived First East Turkestan Republic) in the Chinese Republic. For much of the 20th century, Turkey was the only independent Turkic country.[263]

In 1991, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, five Turkic states gained their independence. These were Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Other Turkic regions such as Tatarstan, Tuva, and Yakutia remained in the Russian Federation. Chinese Turkestan remained part of the People's Republic of China. Immediately after the independence of the Turkic states, Turkey began seeking diplomatic relations with them. Over time political meetings between the Turkic countries increased and led to the establishment of TÜRKSOY in 1993 and the Turkic Council in 2009, which later was renamed Organization of Turkic States in 2021.[264]

Physiognomy

According to historians Joo-Yup Lee and Shuntu Kuang, Chinese official histories do not depict Turkic peoples as belonging to a single uniform entity called "Turks".[265] However "Chinese histories also depict the Turkic-speaking peoples as typically possessing East/Inner Asian physiognomy, as well as occasionally having West Eurasian physiognomy."[265] According to "fragmentary information on the Xiongnu language that can be found in the Chinese histories, the Xiongnu were Turkic",[266] however historians have been unable to confirm whether or not they were Turkic. Sima Qian's description of their legendary origins suggest their physiognomy was "not too different from that of... Han (漢) Chinese population",[266] but a subset of Xiongnu known as the Jie people were described having "deep-set eyes", "high nose bridges" and "heavy facial hair".[266] The Jie may have been Yeniseian, although others maintaining an Iranian affiliation, and regardless of whether or not the Xiongnu were Turkic, they were a hybrid people.[267] According to the Old Book of Tang, Ashina Simo "was not given a high military post by the Ashina rulers because of his Sogdian (huren 胡人) physiognomy."[268] The Tang historian Yan Shigu described the Hu people of his day as "blue-eyed and red bearded"[269] descendants of the Wusun, whereas "no comparable depiction of the Kök Türks or Tiele is found in the official Chinese histories."[269]

Historian Peter Golden has reported that genetic testing of the proposed descendants of the Ashina tribe does seem to confirm a link to the Indo-Iranians, emphasizing that "the Turks as a whole 'were made up of heterogeneous and somatically dissimilar populations'".[273] Historian Emel Esin and Professor Xue Zongzheng have argued that West Eurasian features were typical of the royal Ashina clan of the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and that their appearance shifted to an East Asian one due to intermarriage with foreign nobility. As a result, by the time of Kul Tigin (684 AD), members of the Ashina dynasty had East Asian features.[274][275] A 2023 genetic study found that Empress Ashina (568–578 AD), a Royal Göktürk, had nearly entirely Ancient Northeast Asian origin, weakening the "western Eurasian origin and multiple origin hypotheses".[129] Lee and Kuang believe it is likely "early and medieval Turkic peoples themselves did not form a homogeneous entity and that some of them, non-Turkic by origin, had become Turkicised at some point in history."[276] They also suggest that many modern Turkic-speaking populations are not directly descended from early Turkic peoples.[276] Lee and Kuang concluded that "both medieval Chinese histories and modern DNA studies point to the fact that the early and medieval Turkic peoples were made up of heterogeneous and somatically dissimilar populations."[277]

Like Chinese historians, Medieval Muslim writers generally depicted the Turks as having an East Asian appearance.[278] Unlike Chinese historians, Medieval Muslim writers used the term "Turk" broadly to refer to not only Turkic-speaking peoples but also various non-Turkic speaking peoples,[278] such as the Hephthalites, Rus, Magyars, and Tibetans. In the 13th century, Juzjani referred to the people of Tibet and the mountains between Tibet and Bengal as "Turks" and "people with Turkish features."[279] Medieval Arab and Persian descriptions of Turks state that they looked strange from their perspective and were extremely physically different from Arabs. Turks were described as "broad faced people with small eyes", having light-colored, often reddish hair, and with pink skin,[280] as being "short, with small eyes, nostrils, and mouths" (Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi), as being "full-faced with small eyes" (Al-Tabari), as possessing "a large head (sar-i buzurg), a broad face (rūy-i pahn), narrow eyes (chashmhā-i tang), and a flat nose (bīnī-i pakhch), and unpleasing lips and teeth (lab va dandān na nīkū)" (Keikavus).[281] On Western Turkic coins "the faces of the governor and governess are clearly Mongoloid (a roundish face, narrow eyes), and the portrait have definite old Türk features (long hair, absence of headdress of the governor, a tricorn headdress of the governess)".[282]

In the Ghaznavids' residential palace of Lashkari Bazar, there survives a partially conserved portrait depicting a turbaned and haloed adolescent figure with full cheeks, slanted eyes, and a small, sinuous mouth.[283] The Armenian historian Movses Kaghankatvatsi describes the Turks of the Western Turkic Khaganate as "broad-faced, without eyelashes, and with long flowing hair like women".[284]

Al-Masudi writes that the Oghuz Turks in Yengi-kent near the mouth of the Syr Darya "are distinguished from other Turks by their valour, their slanted eyes, and the smallness of their stature."[278] Later Muslim writers noted a change in the physiognomy of Oghuz Turks. According to Rashid al-Din Hamadani, "because of the climate their features gradually changed into those of Tajiks. Since they were not Tajiks, the Tajik peoples called them turkmān, i.e. Turk-like (Turk-mānand)." Ḥāfiẓ Tanīsh Mīr Muḥammad Bukhārī also related that the Oghuz' 'Turkic face did not remain as it was' after their migration into Transoxiana and Iran. Khiva khan Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur wrote in his Chagatai language treatise Shajara-i Tarākima (Genealogy of the Turkmens) that "their chin started to become narrow, their eyes started to become large, their faces started to become small, and their noses started to become big' after five or six generations". Ottoman historian Mustafa Âlî commented in Künhüʾl-aḫbār that Anatolian Turks and Ottoman elites are ethnically mixed: "Most of the inhabitants of Rûm are of confused ethnic origin. Among its notables there are few whose lineage does not go back to a convert to Islam."[285]

Kevin Alan Brook states that like "most nomadic Turks, the Western Turkic Khazars were racially and ethnically mixed."[286] Istakhri described Khazars as having black hair while Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi described them as having blue eyes, light skin, and reddish hair. Istakhri mentions that there were "Black Khazars" and "White Khazars." Most scholars believe these were political designations: black being lower class while white being higher class. Constantin Zuckerman argues that these "had physical and racial differences and explained that they stemmed from the merger of the Khazars with the Barsils."[287] Old East Slavic sources called the Khazars the "White Ugry" and the Magyars the "Black Ugry."[288] Soviet excavated Khazar remains show Slavic-type, European-type, and a minority Mongoloid-type skulls.[287]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz are mentioned in the New Book of Tang as having the same script and language as the Uyghurs but "The people are all tall and big and have red hair, white faces, and green eyes."[289][note 2] The New Book of Tang also states that the neighboring Boma tribe resembled the Kyrgyz but their language was different, which may imply the Kyrgyz were originally a non-Turkic people, who were later Turkicized through inter-tribal marriages.[289] According to Gardizi, the Kyrgyz were mixed with "Saqlabs" (Slavs), which explains the red hair and white skin among the Kyrgyz, while the New Book states that the Kyrgyz "intermixed with the Dingling."[294][295] The Kyrgyz "regarded those with black eyes as descending from [Li] Ling," a Han dynasty general who defected to the Xiongnu.[296]

In a Chinese legal statute from the early period of the Ming dynasty, the Kipchaks are described as having blond hair and blue eyes. It also states that they had a "vile" and "peculiar" appearance, and that some Chinese people would not want to marry them.[297][298] Russian anthropologist Oshanin (1964: 24, 32) notes that "the 'Mongoloid' phenotype, characteristic of modern Kazakhs and Qirghiz, prevails among the skulls of the Qipchaq and Pecheneg nomads found in the kurgans in eastern Ukraine"; Lee & Kuang (2017) propose that Oshanin's discovery is explainable by assuming that the historical Kipchaks' modern descendants are Kazakhs of the Lesser Horde, whose men possess a high frequency of haplogroup C2's subclade C2b1b1 (59.7 to 78%). Lee and Kuang also suggest that the high frequency (63.9%) of the Y-DNA haplogroup R-M73 among Karakypshaks (a tribe within the Kipchaks) allows inference about the genetics of Karakypshaks' medieval ancestors, thus explaining why some medieval Kipchaks were described as possessing "blue [or green] eyes and red hair.[299]

Byzantine historians of the 11th-12th centuries provided description of Turkmens as very different from the Greeks. Bertrandon de la Broquière, a French traveller to the Ottoman Empire, met with sultan Murad II in Adrianople, and described him in the following terms: "In the first place, as I have seen him frequently, I shall say that he is a little, short, thick man, with the physiognomy of a Tartar. He has a broad and brown face, high cheek bones, a round beard, a great and crooked nose, with little eyes".[300]

Remarks

- ^ For its etymology see Kangar union#Etymology

- ^ 9th-century author Duan Chengshi described the Kyrgyz tribe (Jiankun buluo 堅昆部落) as "yellow-haired, green-eyed, red-mustached [and red-]bearded".[290] New Book of Tang (finished in 1060) describes Alats, a medieval Turkic people, as resembling Kyrgyzes[291] who were "all tall, red-haired, pale-faced, green-irised";[292] New Book of Tang also states that Kyrgyzes regarded black hair as "infelicitous" and insisted that black-eyed individuals were descendants of Han general Li Ling.[293]

Archaeology

- Xinglongwa culture

- Hongshan culture

- Čaatas culture

- Askiz culture

- Kurumchi culture

- Saltovo-Mayaki

- Saymaluu-Tash

- Bilär

- Por-Bazhyn

- Ordu-Baliq

- Jankent

International organizations

There are several international organizations created with the purpose of furthering cooperation between countries with Turkic-speaking populations, such as the Joint Administration of Turkic Arts and Culture (TÜRKSOY) and the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-speaking Countries (TÜRKPA) and the Turkic Council.

The TAKM – Organization of the Eurasian Law Enforcement Agencies with Military Status, was established on 25 January 2013. It is an intergovernmental military law enforcement (gendarmerie) organization of currently three Turkic countries (Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey) and Kazakhstan as observer.

TÜRKSOY

Türksoy carries out activities to strengthen cultural ties between Turkic peoples. One of the main goals to transmit their common cultural heritage to future generations and promote it around the world.[301]

Every year, one city in the Turkic world is selected as the "Cultural Capital of the Turkic World". Within the framework of events to celebrate the Cultural Capital of the Turkic World, numerous cultural events are held, gathering artists, scholars and intellectuals, giving them the opportunity to exchange their experiences, as well as promoting the city in question internationally.[302]

Organization of Turkic States

The Organization of Turkic States, founded on 3 November 2009, by the Nakhchivan Agreement confederation, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey, aims to integrate these organizations into a tighter geopolitical framework.

The member countries are Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and Uzbekistan.[303] The idea of setting up this cooperative council was first put forward by Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev back in 2006. Hungary has announced to be interested in joining the Organization of Turkic States. Since August 2018, Hungary has official observer status in the Organization of Turkic States.[304] Turkmenistan also joined as an observer state to the organization at 8th summit.[305] Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus was admitted to the organization as observer member at the 2022 Samarkand Summit.[306][307]

Demographics

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Southern Europe. As of 2011[update] the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkey and Iran. Additionally, Turkic people are found within Crimea, Altishahr region of western China, northern Iraq, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, Cyprus, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and former Yugoslavia.

A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland.[308] There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchak, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash, and Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.[citation needed]

The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.[309]

Historical population:

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1 AD | 2–2.5 million? |

| 2013 | 150–200 million |

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups' core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

| People | Primary homeland | Population | Modern language | Predominant religion and sect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkish people | Turkey | 70 M | Turkish | Sunni Islam |

| Azerbaijanis | Iranian Azerbaijan, Republic of Azerbaijan | 30–35 M | Azerbaijani | Shia Islam (65%), Sunni Islam (35%)[310][311] (Hanafi). |

| Uzbeks | Uzbekistan | 28.3 M | Uzbek | Sunni Islam |

| Kazakhs | Kazakhstan | 13.8 M | Kazakh | Sunni Islam |

| Uyghurs | Altishahr (China) | 9 M | Uyghur | Sunni Islam |

| Turkmens | Turkmenistan | 8 M | Turkmen | Sunni Islam |

| Tatars | Tatarstan (Russia) | 7 M | Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Kyrgyzs | Kyrgyzstan | 4.5 M | Kyrgyz | Sunni Islam |

| Bashkirs | Bashkortostan (Russia) | 2 M | Bashkir | Sunni Islam |

| Crimean Tatars | Crimea (Russia/Ukraine) | 0.5 to 2 M | Crimean Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Chuvashes | Chuvashia (Russia) | 1.7 M | Chuvash | Orthodox Christianity |

| Qashqai | Southern Iran (Iran) | 0.9 M | Qashqai | Shia Islam |

| Karakalpaks | Karakalpakstan (Uzbekistan) | 0.6 M | Karakalpak | Sunni Islam |

| Yakuts | Yakutia (Russia) | 0.5 M | Sakha | Orthodox Christianity and Turkic Paganism |

| Kumyks | Dagestan (Russia) | 0.4 M | Kumyk | Sunni Islam |

| Karachays and Balkars | Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria (Russia) | 0.4 M | Karachay-Balkar | Sunni Islam |

| Tuvans | Tuva (Russia) | 0.3 M | Tuvan | Tibetan Buddhism |

| Gagauzs | Gagauzia (Moldova) | 0.2 M | Gagauz | Orthodox Christianity |

| Turkic Karaites and Krymchaks | Ukraine | 0.004 M | Karaim and Krymchak | Judaism |

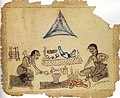

Cuisine

Markets in the steppe region had a limited range of foodstuffs available—mostly grains, dried fruits, spices, and tea. Turks mostly herded sheep, goats and horses. Dairy was a staple of the nomadic diet and there are many Turkic words for various dairy products such as süt (milk), yagh (butter), ayran, qaymaq (similar to clotted cream), qi̅mi̅z (fermented mare's milk) and qurut (dried yoghurt). During the Middle Ages Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Tatars, who were historically part of the Turkic nomadic group known as the Golden Horde, continued to develop new variations of dairy products.[312]

Nomadic Turks cooked their meals in a qazan, a pot similar to a cauldron; a wooden rack called a qasqan can be used to prepare certain steamed foods, like the traditional meat dumplings called manti. They also used a saj, a griddle that was traditionally placed on stones over a fire, and shish. In later times, the Persian tava was borrowed from the Persians for frying, but traditionally nomadic Turks did most of their cooking using the qazan, saj and shish. Meals were served in a bowl, called a chanaq, and eaten with a knife (bïchaq) and spoon (qashi̅q). Both bowl and spoon were historically made from wood. Other traditional utensils used in food preparation included a thin rolling pin called oqlaghu, a colander called süzgu̅çh, and a grinding stone called tāgirmān.[312]

Medieval grain dishes included preparations of whole grains, soups, porridges, breads and pastries. Fried or toasted whole grains were called qawïrmach, while köchä was crushed grain that was cooked with dairy products. Salma were broad noodles that could be served with boiled or roasted meat; cut noodles were called tutmaj in the Middle Ages and are called kesme today.[312]

There are many types of bread doughs in Turkic cuisine. Yupqa is the thinnest type of dough, bawi̅rsaq is a type of fried bread dough, and chälpäk is a deep fried flat bread. Qatlama is a fried bread that may be sprinkled with dried fruit or meat, rolled, and sliced like pinwheel sandwiches. Toqach and chöräk are varieties of bread, and böräk is a type of filled pie pastry.[312]

Herd animals were usually slaughtered during the winter months and various types of sausages were prepared to preserve the meats, including a type of sausage called sujuk. Though prohibited by Islamic dietary restrictions, historically Turkic nomads also had a variety of blood sausage. One type of sausage, called qazi̅, was made from horsemeat and another variety was filled with a mixture of ground meat, offal and rice. Chopped meat was called qïyma and spit-roasted meat was söklünch—from the root sök- meaning "to tear off", the latter dish is known as kebab in modern times. Qawirma is a typical fried meat dish, and kullama is a soup of noodles and lamb.[312]

Religion

Early Turkic mythology and Tengrism

Early Turkic mythology was dominated by Shamanism, Animism and Tengrism. The Turkic animistic traditions were mostly focused on ancestor worship, polytheistic-animism and shamanism. Later this animistic tradition would form the more organized Tengrism.[citation needed] The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763.

The wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Ashina is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse and predatory birds, such as the eagle or falcon, are also main figures of Turkic mythology.[citation needed]

Religious conversions

Buddhism

Buddhism played an important role in the history of Turkic peoples, with the first Turkic state adopting and supporting the spread of Buddhism being the Turkic Shahis and the Göktürks. The Göktürks syncretized Buddhism with their traditional religion Tengrism and also incorporated elements of the Iranian traditional religions, such as Zoroastrianism. Buddhism had its height among the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[313] Buddhism had also considerable impact and influence onto various other historical Turkic groups. In pre-Islamic times, Buddhism and Tengrism coexisted, with several Buddhist temples, monasteries, figures and steles, with images of Buddhist characters and sceneries, were constructed by various Turkic tribes. Throughout Kazakhstan, there exist various historical Buddhist sites, including an underground Buddhist cave monastery. After the Arab conquest of Central Asia, and the spread of Islam among locals, Buddhism (and Tengrism) started to lose ground, however a certain influence of the Buddhist teachings remained during the next centuries.[314]

Tengri Bögü Khan initially made the now extinct Manichaeism the state religion of the Uyghur Khaganate in 763 and it was also popular among the Karluks. It was gradually replaced by the Mahayana Buddhism.[citation needed] It existed in the Buddhist Uyghur Gaochang up to the 12th century.[315]

Tibetan Buddhism, or Vajrayana was the main religion after Manichaeism.[316] They worshipped Täŋri Täŋrisi Burxan,[317] Quanšï Im Pusar[318] and Maitri Burxan.[319] Turkic Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent and west Xinjiang attributed with a rapid and almost total disappearance of it and other religions in North India and Central Asia. The Sari Uygurs "Yellow Yughurs" of Western China, as well as the Tuvans of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples.[320]

Islam

Most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism. Azeris are traditionally Shiite Muslims. Religious observance is less strict in the Republic of Azerbaijan compared to Iranian Azerbaijan.

Christianity

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash of Chuvashia and the Gagauz (Gökoğuz) of Moldova, the vast majority of Chuvash and the Gagauz are Eastern Orthodox Christians.[321][322][323] The traditional religion of the Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam. The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century.[322] As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith.[324] Between the 9th and 14th centuries, Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans.[325] It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period.[326][327][328] It disappeared after its collapse.[329][330]

Kryashens are a sub-group of the Volga Tatars, and the vast majority are Orthodox Christians.[331] Nağaybäk are an indigenous Turkic people in Russia, most Nağaybäk are Christian and were largely converted during the 18th century.[332] Many Volga Tatars were Christianized by Ivan the Terrible during the 16th century, and continued to Christianized under subsequent Russian rulers and Orthodox clergy up to the mid-eighteenth century.[333]

Animism

Today there are several groups that support a revival of the ancient traditions. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many in Central Asia converted or openly practice animistic and shamanistic rituals. It is estimated that about 60% of Kyrgyz people practice a form of animistic rituals. In Kazakhstan there are about 54,000 followers of the ancient traditions.[334][335]

Muslim Turks and non-Muslim Turks

The Uyghur Turks, who once belonged to a variety of religions, were gradually Islamized during a period spanning the 10th and 13th centuries. Some scholars have linked the phenomenon of recently Islamized Uyghur soldiers recruited by the Mongol Empire to the slow conversion of Uyghur populations to Islam.[336][337]

The non-Muslim Turks' worship of Tengri and other gods was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them – The Infidels – May God destroy them![338][339]

The Basmil, Yabāḳu and Uyghur states were among the Turkic peoples who fought against the Kara-Khanids spread of Islam. The Islamic Kara-Khanids were made out of Tukhsi, Yaghma, Çiğil and Karluk.[340]

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu.[341] The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.[342]

Mahmud al-Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as "Uighur dogs" and called them "Tats", which referred to the "Uighur infidels" according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat".[343][344] While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan (meaning Buddha, acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.[345][339]

Old sports

Tepuk

Mahmud al-Kashgari in his Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk, described a game called "tepuk" among Turks in Central Asia. In the game, people try to attack each other's castle by kicking a ball made of sheep leather.[346] (see also: Cuju)

Kyz kuu

Kyz kuu (chase the girl) has been played by Turkic people at festivals since time immemorial.[347]

Jereed

Horses have been essential and even sacred animals for Turks living as nomadic tribes in the Central Asian steppes. Turks were born, grew up, lived, fought and died on horseback. Jereed became the most important sporting and ceremonial game of Turkish people.[348]

Kokpar

The kokpar began with the nomadic Turkic peoples who have come from farther north and east spreading westward from China and Mongolia between the 10th and 15th centuries.[349]

Jigit

"jigit" is used in the Caucasus and Central Asia to describe a skillful and brave equestrian, or a brave person in general.[350]

Gallery

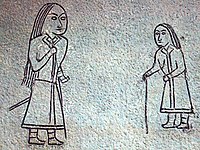

Battle, hunting and blacksmithing scenes in Turkic rock art of the early Middle Ages in Altai

-

Turk vassal blacksmiths under Mongolian rule

-

Turkic hunting scene, Gokturk period Altai

-

Battle scene of a Turkic horseman with typical long hair (Gokturk period, Altai)

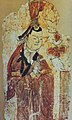

Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Old Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes.

-

Old Uyghur king from Turfan, from the murals at the Dunhuang Mogao Caves.

-

Old Uyghur prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur woman from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur Princess.

-

Old Uyghur Princesses from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur Princes from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur Prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur Manichaean Elect depicted on a temple banner from Qocho.

-

Old Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Old Uyghur Manichaean Electae from Qocho.

-

Old Uyghur Manichaean clergymen from Qocho.

-

Manicheans from Qocho

Medieval times

Modern times

-

Azerbaijani girls in traditional dress.

-

Bashkir boys in national dress.

-

A Chuvash girl in traditional dress.

-

Khakas people with traditional instruments.

-

Nogai man in national costume.

-

Turkish girls in their traditional clothes, Dursunbey, Balikesir Province.

-

Turkmen girl in national dress.

-

Kazakh man in traditional clothing.

-

Uzbek with traditional cuisine.

-

Kyrgyz traditional eagle hunter.

-

Tuvan traditional shaman.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Yunusbayev et al. 2015.

- ^ Garibova, Jala (2011), "A Pan-Turkic Dream: Language Unification of Turks", in Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (eds.), Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts, Oxford University Press, p. 268, ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1,

Approximately 200 million people,... speak nearly 40 Turkic languages and dialects. Turkey is the largest Turkic state, with about 60 million ethnic Turks living in its territories.

- ^ Hobbs, Joseph J. (2017), Fundamentals of World Regional Geography, Cengage, p. 223, ISBN 978-1-305-85495-6,

The greatest are the 65 million Turks of Turkey, who speak Turkish, a Turkic language...

- ^ "Uzbekistan". Statistics Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan. 19 August 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2022. "Population: 34,600,000 (January 2021 est.)" "Ethnic groups: Uzbek 84.6%, Russian 2.1%, Tajik 4.9%, Kazakh 2.4%, Karakalpak 2.2%, other 4.1% (2021 est.)" Assuming Uzbek, Kazakh and Karakalpak are included as Turks, 84.6% + 2.4% + 2.2% = 89.2%. 89.2% of 34.6m = 31.9m

- ^ "Azerbaijani (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2012. (15 million)

- ^ Egbert Jahn, (2009). Nationalism in Late and Post-Communist Europe, p. 293 (20 mil)

- ^ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division – Country Profile: Iran, May 2008, page 5 [1]

- ^ "Kazakhstan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 21 December 2014. "Population: 17,948,816 (July 2014 est.)" "Ethnic groups: Kazakh (Qazaq) 63.1%, Russian 23.7%, Uzbek 2.9%, Ukrainian 2.1%, Uighur 1.4%, Tatar 1.3%, German 1.1%, other 4.4% (2009 est.)" Assuming Kazakh, Uzbek, Uighur and Tatar are included as Turks, 63.1% + 2.9% + 1.4% + 1.3% = 68.7%. 68.7% of 17.9m = 12.3m

- ^ "China". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 30 July 2016. "Population: 9,780,780 (July 2015 est.)"

- ^ "Census 2021: 84.6% of population define themselves as Bulgarians, 8.4% Turks, 4.4% Roma". 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Uzbeks and Turkmens – Minorities and indigenous peoples in Afghanistan". World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. 19 June 2015.

- ^ Turner, B. (7 February 2017). The Statesman's Yearbook 2007: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. p. 1238. ISBN 978-0-230-27135-7.

- ^ Leitner, Gerhard; Hashim, Azirah; Wolf, Hans-Georg (11 January 2016). Communicating with Asia: The Future of English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-107-06261-0.

- ^ Dresser, Norine (7 January 2011). Multicultural Manners: Essential Rules of Etiquette for the 21st Century. Wiley. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-118-04028-7.

- ^ "Unpublished Census Provides Rare and Unvarnished Look at Turkmenistan". Jamestown.

- ^ "First (actual) demographic data for Turkmenistan released". www.asianews.it.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-317-42368-3

- ^ Bassem, Wassim (2016). "Iraq's Turkmens call for independent province". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016.

- ^ "Tajikistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Obama, recognize us". St. Louis American. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Nahost-Informationsdienst (ISSN 0949-1856): Presseausschnitte zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft in Nordafrika und dem Nahen und Mittleren Osten. Autors: Deutsches Orient–Institut; Deutsches Übersee–Institut. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient–Institut, 1996, seite 33.

- ^ "All-Ukrainian population census 2001 – General results of the census – National composition of population". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ TRNC SPO, Economic and Social Indicators 2014, pages=2–3

- ^ Michael, Michális (29 April 2016). Reconciling Cultural and Political Identities in a Globalized World: Perspectives on Australia-Turkey Relations. Springer. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-137-49315-6.

- ^ "Mongolia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "2020 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS OF MONGOLIA /summary/". Archived from the original on 15 July 2021.

- ^ Al-Akhbar. "Lebanese Turks Seek Political and Social Recognition". Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Tension adds to existing wounds in Lebanon". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Ahmed, Yusra (2015), Syrian Turkmen refugees face double suffering in Lebanon, Zaman Al Wasl, archived from the original on 23 August 2017, retrieved 11 October 2016

- ^ "Syria's Turkmen Refugees Face Cruel Reality in Lebanon". Syrian Observer. 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ "2017 Anuarul Statisitc al Republicii Moldova" (PDF) (in Romanian). Biroul Național de Statistică al Republicii Moldova. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "North Macedonia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002" (PDF). Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica. Turkic peoples. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to the Turkic subfamily..."

- ^ Yunusbayev et al. 2015, p. 1. "The Turkic peoples represent a diverse collection of ethnic groups defined by the Turkic languages."

- ^ Uchiyama et al. 2020: "Most linguists and historians agree that Proto-Turkic, the common ancestor of all ancient and contemporary Turkic languages, must have been spoken somewhere in Central-East Asia (e.g. Róna-Tas, Reference Róna-Tas1991, p. 35; Golden, Reference Golden1992, pp. 124–127; Menges, Reference Menges1995, pp. 16–19)."

- ^ a b Golden 2011, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Uchiyama et al. 2020: "The ultimate Proto-Turkic homeland may have been located in a more compact area, most likely in Eastern Mongolia"

- ^ a b Lee & Kuang 2017: "The best candidate for the Turkic Urheimat would then be northern and western Mongolia and Tuva, where all these haplogroups could have intermingled, rather than eastern and southern Mongolia..."

- ^ Uchiyama et al. 2020:"To sum up, the palaeolinguistic reconstruction points to a mixed subsistence strategy and complex economy of the Proto-Turkic-speaking community. It is likely that the subsistence of the Early Proto-Turkic speakers was based on a combination of hunting–gathering and agriculture, with a later shift to nomadic pastoralism as an economy basis, partly owing to the interaction of the Late Proto-Turkic groups with the Iranian-speaking herders of the Eastern Steppe."

- ^ Findley 2005, p. 18: "Moreover, Turks do not all physically look alike. They never did. The Turks of Turkey are famous for their range of physical types. Given the Turks' ancient Inner Asian origins, it is easy to imagine that they once presented a uniform Mongoloid appearance. Such traits seem to be more characteristic in the eastern Turkic world; however, uniformity of type can never have prevailed there either. Archeological evidence indicates that Indo-Europeans, or certainly Europoid physical types, inhabited the oases of the Tarim basin and even parts of Mongolia in ancient times. In the Tarim basin, persistence of these former inhabitants' genes among the modern Uyghurs is both observable and scientifically demonstrable.32 Early Chinese sources describe the Kirghiz as blue-eyed and blond or red-haired. The genesis of Turkic ethnic groups from earliest times occurred in confederations of diverse peoples. As if to prove the point, the earliest surviving texts in Turkic languages are studded with terms from other languages."