Sexual economics

Sexual economics relates to how participants think, feel, behave and give feedback during sex or relevant sexual events. This theory states that the thinking, preferences and behavior of men and women follow the fundamental economic principles.[1] It was proposed by psychologists Roy Baumeister and Kathleen Vohs.

Definitions[edit]

Sexual Economics defines sex as a marketplace deal. In this theory, sex is the thing that women have, and men want. Therefore, sex is considered as a resource that women hold overall. Women hold on to their bodies until they receive enough motivation to give it up, such as love, commitment, time, attention, caring, loyalty, respect, happiness and money from another party. On the other side, men are the ones who offer the resources that entice women into sex.[1]

Sexual Economics is based on social exchange theory: people are willing to give up something if they can get in exchange what they believe will benefit them more.[2] As an example, assume one party holds a burger, and a hungry man wants the burger more than the money in his pocket. In this situation, the party who holds the burger has to want the money more than he wants the burger for the final exchange to take place. However, sometimes one party is more eager to exchange for what the other party holds, this causes a bargaining power imbalance.[3] At this point, the party who is less willing to exchange what they have has a higher control in this relationship. In the example of a sexual relationship, if one side wants to have sexual intercourse less than the other, he or she can hold out until a more attractive offer is made.[4]

In the view of Mark Regnerus, the economic perspective is clear. The behavior he analyzed in the market place states that the majority rule is a political principle that often works in human society, but sex is an exception and minority rules work are applicable.[5]

Female and male status[edit]

Sexual intercourse is often more attractive (if the state of affairs is equal for both parties, e.g., a man and a woman with equal economic status) to men than to women.[citation needed] In primates, male aggression against females has the effect of controlling female sexuality for the male's reproductive advantage. Furthermore, the evolutionary perspective provides a hypothesis to help explain cross-culture variation in the frequency of male aggression against women. Variables include the protection of women by family or community, male alliances, and male strategies for protecting spouses and achieving adulterous mating and male resource control.[6]

According to sexual economics theory, males and females are different both physically and physiologically. Men give women resources, and then women will allow sex to take place. Under the context of sex, the trade of sex and resources keeps happening through eras and cultures, and society has acknowledged that female sexuality has more value than male sexuality.[citation needed] For instance, men and women have different feelings about their virginity. Women are more likely to think of their virginity as a precious gift and cherish it, while men see their virginity as a shameful condition and want to get rid of it early in life.[7]

It is also claimed that prostitution (the exchange of sex for money or equivalent items) may be a threat to women's status because sex is mostly considered as part of an intimate relationship instead of a contract.[8]

Society situations[edit]

Domestic violence[edit]

Some examples could be used to prove that the theory of the sex economy valid. In a violent relationship, women are more likely to receive violence compared to men. In a research study, the results showed that jealousy is the most often used explanation for domestic violence for women,[9] but for men two emotions lead to violence. The first one involves destructive thoughts (also refers to "critical inner voice") dominant like "She's trying to fool you" or "You are not man enough if you don't control her in mind and body." The other element contains a detrimental illusion (also refers to "fantasy bond"), it brings a sense that another person constituted a whole with you, and it is essential for your happiness.[10]

Several advances in promoting equality between sexes have been made (such as abortion law modification in some areas), but most societies are still patriarchal societies. Men are thought of as stronger than women, especially physically. The expectation of being masculine and more powerful than women could be destructive for men by leading to violence. Therefore, a woman who has a violent partner would choose to offer sex to comfort and mostly distract them from abusing her. In this case, trading sex is considered as one useful way for women to escape emotional and physical abuse from men in a violent relationship.[1]

Adultery[edit]

The punishment for adultery is different between different genders in some countries. In some cultures, adultery is considered a crime, and although punishments for adultery such as stoning are also applied to men, the vast majority of the victims are women.[11] In some cultures, the wives' adultery can be a viable reason if the husband wants to divorce, however, husbands' adultery cannot justify divorce. This is the evidence for sex being considered a female resource. In this situation, sex is traded in exchange for getting married; therefore, if a wife has sex outside her husband, she's giving away what her husband sees as his.

In the Philippines, the law differentiates based on gender. A woman can be charged as a criminal of adultery if she has had sexual intercourse with someone other than her husband. However, a man can only be charged with crimes such as concubinage, either keeping his mistress at home, or co-habitating with her, or having sexual relationships under scandalous circumstances.[12]

Pornography[edit]

There is a big difference between men and women on the topic of their personal use and acceptance of pornography.[13] It is shown in many research papers that men are more likely to view pornography compared to women, the most obvious evidence is that there are more male users on pornography websites than female users. Pornhub, as one of the biggest pornography websites in the world, reported of the year at the end of 2019.[14] There were 32% female users in 2019, while 68% of Pornhub users were male, which means the number of male users was two times more than female users worldwide.[15] Therefore, at least watching sex is more attractive to men than women based on the data derived.

Porn stars[edit]

Porn stars are people who perform sex acts in front of cameras for pornographic videos/movies. Female porn stars enter the industry for many different reasons, such as being repressed for a long time and wanting to abreact via this job. Receiving a satisfying pay after each movie ($390-$1950 for female actor)[16] is also one of the attractive factors for entering the pornography industry.[17]

However, health care for porn stars is in a lack of security and in some porn women are degraded and used in some scenes. Women in porn can become dehumanized and treated as objects, abused, broken and discarded at the end.[18] Therefore, even in commercial sexual culture, sexism and misogynist violence still exist in today's society.

Human trafficking[edit]

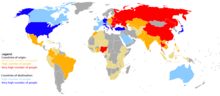

Human trafficking is a global issue and has consistently existed for centuries, nevertheless, it entered public consciousness around the beginning of the twenty-first century.[19] Human trafficking is the process of enslaving people and exploiting them.[20] Sex trafficking is one of the most common types of human trafficking. According to the data derived by The United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime[21] in 2016, 51% identified victims of human trafficking were women, children made up 28% and 21% were men. 72% of those who were exploited in the sex industry were women, while 63% of identified traffickers were men.[22] Most victims are placed in abusive and coercive situations, but escaping is also difficult and life-threatening for them.[23]

According to The International Labor Organization, 4.5 million people are affected by sex trafficking in the world.[24] Sex trafficking victims are often caught by various prosecuted criminal activities such as illegal prostitution. Besides the law, problems like long-lasting problems such as disease (AIDS), malnutrition, psychological trauma, addiction to drugs, and social ostracism against this group of people should be addressed as well.

Sex bribery in the work place[edit]

Sex bribery is defined as a "form of quid pro quo harassment in a sexual relationship with the declared or implicit condition for acquiring/retaining employment or its benefit" [25] in an employment setting. A common example of sex bribery might come down to sexual activity or sexually related behavior accompanied by a reward such as a promotion opportunity or raise in payment.[26] In a workplace, attempted coercion of sexual activity may under the threat of two major types of punishment: negative work performance feedback/evaluation and withheld chances of promotions and raises.[27]

According to the 2016 Personal Safety Survey,[28] around 55% of women over 18 have experienced sexual harassment in their lifetime, including receiving indecent phone calls, texts, emails; indecent exposure; inappropriate comments about the person's body and sex life; having unwanted touching, grabbing and kissing; and exposing and distributing the person's text, pictures, and sexual videos, without the person's permission. It is a serious, widespread problem, and the person who has a sexual harassment experience can feel stressed, anxious and depressed, sometimes withdrawing socially, becoming less productive, and losing confidence and self-esteem.[29]

Social cases: sex as a female resource[edit]

There are several controversial cases in today's society that are relevant to sex economic theory.

Virginity Auction[edit]

A virginity auction is a controversial auction often published online. The person who tries to sell his/her virginity is often a young female, and the winning bidder will have the opportunity to be the first who have intercourse with the person. It is a controversial topic since many cases cannot be certified to be authentic.[30][31][32] The person who auctions their virginity mostly do so for quick financial help. In this case, under the theory of sex economics, women are trying to use sex as a resource to trade financial help from men.

Sugar baby[edit]

Sugar baby is another controversial case that exists in today's society. A sugar baby and sugar daddy/mommy are in a beneficial relationship, which means sugar babies provide time and sexual services to please their partners, and sugar daddies/mommas give financial support back to sugar babies including helping them in student loans and also provide luxury lifestyles such as expensive items they couldn't afford on their own. According to the registered number on dating websites,[33] sugar babies are mostly female and the number of sugar daddy is distinctly more than the number of sugar mommy. Therefore, it is another instance that corresponds to the theory of the sex economy.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D. (November 2004). "Sexual Economics: Sex as Female Resource for Social Exchange in Heterosexual Interactions". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (4): 339–363. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_2. ISSN 1088-8683. PMID 15582858. S2CID 15191559.

- ^ Roloff, Michael E. (1981). Interpersonal communication: the social exchange approach. Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-1604-3. OCLC 7307310.

- ^ Plummer, Ken (2002-11-01). Telling Sexual Stories. doi:10.4324/9780203425268. ISBN 9780203425268.

- ^ Delaney, Sheila (1975). "Sexual Economics, Chaucer's Wife of Bath, and The Book of Margery Kempe". Minnesota Review. 5 (1): 104–115. ISSN 2157-4189.

- ^ Regnerus, Mark; Uecker, Jeremy (2010-12-10). Premarital Sex in America. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199743285.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-974328-5.

- ^ Smuts, Barbara (March 1992). "Male aggression against women". Human Nature. 3 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1007/bf02692265. ISSN 1045-6767. PMID 24222394. S2CID 7627612.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D. (2012-10-18). "Sexual Economics, Culture, Men, and Modern Sexual Trends". Society. 49 (6): 520–524. doi:10.1007/s12115-012-9596-y. ISSN 0147-2011.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F.; Twenge, Jean M. (2003-04-15). "The Social Self". Handbook of Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471264385.wei0514. ISBN 0-471-26438-5.

- ^ Pirog-Good, Maureen A.; Stets, Jan E. (January 1991). "Violence in Dating Relationships". Family Relations. 40 (1): 117. doi:10.2307/585669. ISSN 0197-6664. JSTOR 585669.

- ^ Firestone, Robert W.; Firestone, Lisa A.; Catlett, Joyce (2006). Sex and love in intimate relationships. doi:10.1037/11260-000. ISBN 1-59147-286-5.

- ^ "Gender Inequality and Discrimination: The Case of Iranian Women". Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ "A brief discussion on Infidelity, Concubinage, Adultery and Bigamy". Philippine e-Legal Forum. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ Hald, Gert Martin (2006-10-01). "Gender Differences in Pornography Consumption among Young Heterosexual Danish Adults". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 35 (5): 577–585. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9064-0. ISSN 1573-2800. PMID 17039402. S2CID 35560724.

- ^ "The 2019 Year in Review – Pornhub Insights".

- ^ "The 2019 Year in Review – Pornhub Insights".

- ^ Griffiths, Josie (2017-02-21). "This is how much porn stars get paid". News.com.au. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ Escoffier, Jeffrey (2007-08-01). "Porn Star/Stripper/Escort: Economic and Sexual Dynamics in a Sex Work Career". Journal of Homosexuality. 53 (1–2): 173–200. doi:10.1300/J082v53n01_08. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 18019074. S2CID 6367311.

- ^ "PsycNET". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- ^ Kempadoo, Kamala; Sanghera, Jyoti; Pattanaik, Bandana (2015-12-03). Trafficking and Prostitution Reconsidered: New Perspectives on Migration, Sex Work, and Human Rights. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-26451-4.

- ^ Snow, Melissa; Vardaman, Samantha Healy; Smith, Linda (2009). "The National Report on Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking: America's Prostituted Children".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "International Labour Organization". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ "United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ Macy, Rebecca J.; Graham, Laurie M. (2012-04-01). "Identifying Domestic and International Sex-Trafficking Victims During Human Service Provision". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 13 (2): 59–76. doi:10.1177/1524838012440340. ISSN 1524-8380. PMID 22491971. S2CID 35568730.

- ^ "Sex Trafficking | Human Trafficking for Sex – End Slavery Now". endslaverynow.org. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ "Sexual Bribery". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ "Abstracts Database – National Criminal Justice Reference Service". www.ncjrs.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1979). Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02299-5.

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (2017-11-08). "Main Features – Experience of Sexual Harassment". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fitzgerald, Louise F; Shullman, Sandra L; Bailey, Nancy; Richards, Margaret; Swecker, Janice; Gold, Yael; Ormerod, Mimi; Weitzman, Lauren (1988-04-01). "The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 32 (2): 152–175. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(88)90012-7. ISSN 0001-8791.

- ^ "18yo selling virginity for $100k". Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ Gordon, Claire (2010-02-09). "How Much Is Virginity Worth?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ Carpenter, Laura (2005-11-01). Virginity Lost: An Intimate Portrait of First Sexual Experiences. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7200-3.

- ^ Charlton, James I. (1998-03-27). "Nothing About Us without Us". Nothing About Us Without Us Disability Oppression and Empowerment. University of California Press. pp. 3–18. doi:10.1525/california/9780520207950.003.0001. ISBN 978-0-520-20795-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)