Hudson Heights, Manhattan

Hudson Heights | |

|---|---|

The highest point on Manhattan is in Bennett Park; the inset shows the marker seen on the lower right of the larger image | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Population | |

| • Total | 20,000 (2010) |

| Time zone | UTC– 05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC– 04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 10033 and 10040 |

Hudson Heights is a residential neighborhood within Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan, New York City. Most residences are apartment buildings, many of which are cooperatives, and most were constructed in the 1920s through 1940s. The Art Deco style is prominent, along with Tudor Revival. Notable complexes include Hudson View Gardens and Castle Village, which were both developed by Dr. Charles V. Paterno, and were designed by George F. Pelham and his son, George F. Pelham, Jr., respectively.

The neighborhood is located on a plateau[1] on top of a bluff overlooking both the Hudson River on the west and the Broadway valley of Washington Heights on the east. Hudson Heights includes the highest natural point in Manhattan, located in Bennett Park. At 265 feet (81 m) above sea level, it is a few dozen feet lower than the torch on the Statue of Liberty.[2]

At the northern end of the neighborhood, where Cabrini Boulevard meets Fort Washington Avenue at Margaret Corbin Circle, is Fort Tryon Park, conceived by John D. Rockefeller Jr., designed by the Olmsted Brothers, and given to the city by Rockefeller in 1931.[3] The park contains within it The Cloisters – also conceived of by Rockefeller – which houses the Medieval art collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Boundaries and geography[edit]

Similar to many other neighborhoods that are undergoing gentrification in New York City, this Washington Heights area was renamed by real estate brokers in the 1990s to appeal to a different type of community than was attracted to other parts of Washington Heights.[4]

Like many New York City neighborhoods, the boundaries of Hudson Heights are imprecise.[notes 1] One definition has it bounded by the Hudson River to the west, Broadway to the east, 173rd Street to the south, and Fort Tryon Park to the north,[5][6][7][8] but another would limit the neighborhood to the top of the high ridge which physically separates it from the rest of Washington Heights. By this definition, Hudson Heights is bounded in the west by the Henry Hudson Parkway, in the east by Fort Washington Avenue, in the south by West 181st Street and in the north by Fort Tryon Park.[4] The ridge the neighborhood sits on overlooks the river to the west and the Broadway valley to the east. In 2018, The New York Times defined it as being bordered by 173rd Street in the south, Bennett Avenue in the east, the northern boundary of Fort Tryon Park in the north, and the Hudson River in the west.[9]

Using the more restrictive boundaries, the neighborhood's main north–south thoroughfares are Fort Washington Avenue (two-way), Pinehurst Avenue (one way south) and Cabrini Boulevard (formerly Northern Avenue, one way north). Riverside Drive runs intermittently along the bottom of the ridge to the west, while Bennett Avenue and Overlook Terrace do the same on the east, with Overlook Avenue climbing to the top of the ridge at West 190th Street. The east–west streets are all numbered, from West 181st Street to West 190th Street, but none of those streets, with the exception of West 181st at the southern end of the ridge, cross all the way through the neighborhood: they are all interrupted at one point or another.[10]

History[edit]

17th century[edit]

Before European explorers and settlers, the Lenape Indians lived on the island they called Mannahatta. Just to the north of Hudson Heights, in what is now Inwood Hill Park, the Lenape tribe exchanged the island for items worth about 60 Dutch Gilders in a deal with Peter Minuit in 1626. He named the island New Amsterdam. The area north of central Manhattan was called Niew Haarlem until the British gained control of the area during the Revolutionary War. They renamed the area Lancaster, and gave it a northern border near what is now 129th Street. The ridge that overlooks the Hudson River was once inhabited by the Wecquaesgeek Indians and called Chquaesgeck. Later it was called Lange Bergh (Long Hill) by Dutch settlers until the 17th century.[3]

18th and 19th centuries[edit]

In the 18th century, only the southern portion of the island was settled by Europeans, leaving the rest of Manhattan largely untouched. Among the many unspoiled tracts of land was the highest spot on the island, which provided unsurpassed views of what would become the New York metropolitan area.[11]

When the Revolutionary War came to New York, the British had the upper hand. General George Washington and troops from his Continental Army camped on the high ground, calling it Fort Washington, to monitor the advancing Redcoats. The Continental Army retreated from its location after their defeat on November 16, 1776, in the Battle of Fort Washington.[12] The British took the position and renamed it Fort Knyphausen in honor of the leader of the Hessians, who had taken a major part in the British victory.[13] Their location was in the spot now called Bennett Park. Fort Washington had been established as an offensive position to prevent British vessels from sailing north on the Hudson River. Fort Lee, across the river, was its twin, built to assist in the defense of the Hudson Valley.[11]

Not far from the fort was the Blue Bell Tavern, located on an intersection of Kingsbridge Road, where Broadway and West 181st Street intersect today, on the southeastern corner of modern-day Hudson Heights.[14] On July 9, 1776, when New York's Provincial Congress assented to the Declaration of Independence, "A rowdy crowd of soldiers and civilians ('no decent people' were present, one witness said later) ... marched down Broadway to Bowling Green, where they toppled the statue of George III erected in 1770. The head was put on a spike at the Blue Bell Tavern ... "[14]

The tavern was later used by Washington and his staff when the British evacuated New York, standing in front of it as they watched the American troops march south to retake New York.[15]

By 1856 the first recorded home had been built on the site of Fort Washington. The Moorewood residence was there until the 1880s. The property was purchased by Richard Carman and sold to James Gordon Bennett Sr. for a summer estate in 1871. Bennett's descendants later gave the land to the city to build a park honoring the Revolutionary War encampment. Bennett Park is a portion of that land. Lucius Chittenden, a New Orleans merchant, built a home on land he bought in 1846 west of what is now Cabrini Boulevard and West 187th Street.[16] It was known as the Chittenden estate by 1864.[15] C. P. Bucking, a manufacturer of sheepskins,[17] named his home on land near the Hudson "Pinehurst", a name that survives as Pinehurst Avenue.[16]

Early to mid-20th century[edit]

At the turn of the 20th century the woods started being chopped down to make way for homes. The area was settled by Irish immigrants in the early years of the century.

The cliffs that are now Fort Tryon Park held the mansion of Cornelius Kingsley Garrison Billings, a retired president of the Chicago Coke and Gas Company. He purchased 25 acres (100,000 m2) and constructed Tryon Hall, a Louis XIV-style home designed by Gus Lowell. It had a galleried entranceway from the Henry Hudson Parkway that was 50 feet (15 m) high and made of Maine granite.[18][19] In 1917, Billings sold the land to John D. Rockefeller Jr. for $35,000 per acre. Tryon Hall was destroyed by fire in 1925. The estate was the setting for the book The Dragon Murder Case by S. S. Van Dine,[20] in which detective Philo Vance had to solve a murder on the grounds of the estate, where a dragon was supposed to have lived.[15]

Fort Tryon[edit]

The beginning of this section of Washington Heights as a neighborhood-within-a-neighborhood seems to have started around this time, in the years before World War II. One scholar refers to the area in 1940 as "Fort Tryon" and "the Fort Tryon area." In 1989, Steven M. Lowenstein wrote, "The greatest social distance was to be found between the area in the northwest, just south of Fort Tryon Park, which was, and remains, the most prestigious section ... This difference was already remarked in 1940, continued unabated in 1970 and was still noticeable even in 1980..."[21]

Lowenstein considered Fort Tryon to be the area west of Broadway, east of the Hudson, north of West 181st Street, and south of Dyckman Street, which includes Fort Tryon Park. He writes, "Within the core area of Washington Heights (between 155th Street and Dyckman Street) there was a considerable internal difference as well. The further north and west one went, the more prestigious the neighborhood..."[21]

During World War I, immigrants from Hungary and Poland moved in next to the Irish.[22] Then, as Nazism grew in Germany, Jews fled their homeland. By the late 1930s, more than 20,000 refugees from Germany had settled in Washington Heights.[23]

Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson[edit]

In the years after World War II, the neighborhood was referred to as Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson due to the dense population of German and Austrian Jews who had settled there.[24] A disproportionately large number of Germans who settled in the area had come from Frankfurt-am-Main, possibly giving rise to new name.[21] No other neighborhood in the city was home to so many German Jews, who had created their own central German world in the 1930s.[25]

So cosmopolitan was that world that in 1934 members of the German-Jewish Club of New York started Aufbau, a newsletter for its members that grew into a newspaper. Its offices were nearby on Broadway.[26] The newspaper became known as a "prominent intellectual voice and a main forum for German Jewry in the United States," according to the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. "It featured the work of great prominent writers and intellectuals such as Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Stefan Zweig, and Hannah Arendt. It was one of the only newspapers to report on the atrocities of the Holocaust during World War II."[27]

In 1941 it published the Aufbau Almanac, a guide to living in the United States that explained the American political system, education, insurance law, the post office and sports.[28] After the war, Aufbau helped families that had been scattered by European battles to reconnect by listing survivors' names.[29] Aufbau's offices eventually moved to the Upper West Side. The paper nearly went bankrupt in 2006, but was purchased by Jewish Media AG, and exists today as a monthly news magazine. Its editorial offices are now in Berlin, but it keeps a correspondent in New York.[30]

When the children of the Jewish immigrants to the Hudson Heights area grew up, they tended to leave the neighborhood, and sometimes, the city. By 1960 German Jews accounted for only 16% of the population in Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson.[22] The neighborhood became less overtly Jewish into the 1970s as Soviet immigrants moved to the area.

After the Soviet immigration, families from the Caribbean, especially Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, made it their home. So many Dominicans live in Washington Heights that candidates for the presidency of the Dominican Republic campaign in parades in the area.[31] In the 1980s African-Americans began to move in, followed shortly by other groups. "Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson" no longer described the area.

Late 20th and early 21st centuries[edit]

"Hudson Heights" began to be used as a name for the neighborhood around 1993.[8][33] Neighborhood activists formed a group in late 1992 to help promote the neighborhood[34] and after considering several names, settled on the one that became part of their organization's name: Hudson Heights Owners' Coalition. According to one of the group's founders, real estate brokers did not start using the name until after the group was formed.[33]

The new name replaced the outdated reference to German heritage, which some have criticized, even though the German-speaking population is negligible at best.[35] Although many Russian speakers still live there, Spanish-speakers vastly outnumber the Russophones, and English remains the lingua franca.

Elizabeth Ritter, the president of the owners' group, said, "We didn't set out to change the name of the neighborhood, but we were careful in how we selected the name of the organization."[36] In 2011, Curbed New York published on article which used Hudson Heights as an example of "How to Gentrify a Neighborhood", the first step of which was "Create a nickname to separate the area from its crime-riddled past."[37]

Today the name "Hudson Heights" has been adopted by arts organizations such as Hudson Heights Duo and the Hudson Heights String Academy, and businesses including Hudson Heights Pediatrics and Hudson Heights Restoration. Newspapers from The Wall Street Journal[38] and the New York Times[39] to The Village Voice[40] use the name in reference to the neighborhood, as did The New York Sun before it went bankrupt,[24] Money magazine in its November 2007 article named Hudson Heights the best neighborhood to retire to in New York City.[41] "Hudson Heights" was used by Gourmet magazine in its September 2007 article about dining in Washington Heights,[42] and by The New Yorker in May 2016 about a concert in The Cloisters.[43]

Demographics and real estate[edit]

The 2010 census determined that the population of the neighborhood, using the larger definition of its boundaries, south to West 173rd Street, to be 29,000, with 44% being non-Hispanic whites, and 43% Hispanic.[8]

In 2012, the average co-op in the neighborhood sold for $388,000, while in 2013 the average price was $397,000. In 2012 166 were sold, while 244 were sold in 2013. Rents were around $1,400 per month for a studio apartment, $1,700–$2,000 for a one-bedroom apartment, and around $3,000 for a two-bedroom; prices were higher if the apartments for sublets in a co-op building.[8]

Residences[edit]

Nearly every structure was built before World War II – which in New York real estate parlance is referred to as pre-war – many of them in the Art Deco style. Facades in the Tudor are also well represented, while others are in the Art Nouveau, Neo-Classical, and Collegiate Gothic styles. Many of the apartment houses are co-ops and a few are condos; the remainder are still rental buildings.

The largest residential complexes in the area were started by real estate developer Dr. Charles V. Paterno; Hudson View Gardens opened in 1924 and was originally started and sold as a housing cooperative. The Tudor-style complex was designed by the architect George F. Pelham, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.[9] Pelham also designed The Pinehurst on Fort Washington Avenue at West 180th Street, which opened in 1908.[44] Paterno is remembered by the Paterno Trivium,[45] erected in spring 2000 at the intersection of Cabrini Boulevard, Pinehurst Avenue and West 187th Street.

Pelham's son, George F. Pelham Jr., was the architect of Castle Village, on the other side of Cabrini Boulevard. This series of five buildings was finished in 1939 and converted to a co-op in 1985. On May 12, 2005 a large, 65-foot high retaining wall separating the Castle Village complex from the Henry Hudson Parkway collapsed onto the northbound lanes of the parkway and the 181st Street northbound on-ramp. Portions of the wall were nearly 100 years old according to records indicating the wall was constructed between 1905 and the 1930s.[46] The collapse lead to the on-ramp's closure for over two and half years; the entrance was reopened in March 2008.[47]

Beginning in the 1980s, some rental buildings in the area started converting to housing cooperatives or condominiums. In recent years, Hudson Heights has been an attractive area for homebuyers who want to stay in Manhattan but who can't afford downtown prices, or who want larger homes than those in the rest of Manhattan.[41][48] The multiple co-ops and condos in the area formed the Hudson Heights Owners Coalition in 1993.[49]

Another large cooperative is the 16-story Cabrini Terrace at 900 West 190th Street,[50] the tallest building in the neighborhood. Members of the co-op's board successfully lobbied the legislature to change the law that grants tax credits for the installation of solar panels in residences to include apartment buildings, which had been excluded.[51] Cabrini Terrace inaugurated its solar panels at a ceremony on January 24, 2008.

Culture, food and shopping[edit]

A widely known museum in the area is The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park, where the Metropolitan Museum of Art houses and displays its collection of Medieval art. In September, the park hosts the Medieval Festival, a free fair with costumed revelers, food and music.[52] In its September 2007 issue, Gourmet described the Dominican restaurants in Washington Heights and Inwood, including many in Hudson Heights.[42]

Hudson Heights is among the neighborhoods of Upper Manhattan that participate in The Art Stroll, an annual festival of the arts which highlights local artists. Public places in Washington Heights, Inwood and Marble Hill host impromptu galleries, readings, performances and markets over several weeks each summer.[53]

Bennett Park is the location of the highest natural point in Manhattan, as well as a commemoration on the east side of the park of the walls of Fort Washington, which are marked in the ground by stones with an inscription that reads: "Fort Washington Built And Defended By The American Army 1776." Land for the park was donated by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publisher of the New York Herald. His father, James Gordon Bennett, Sr., bought the land and was previously the Herald's publisher. Bennett Park hosts the annual Harvest Festival in September and the children's Halloween Parade – with trick-or-treating afterwards – on All Hallow's Eve.

Many small shops are located on West 181st Street at the southern end of the neighborhood, and all along Broadway near to its border. In the middle of the neighborhood itself, there is a small shopping area at West 187th Street between Cabrini Boulevard and Fort Washington Avenue.

News of Upper Manhattan is published weekly in The Manhattan Times, a bilingual newspaper. Its annual restaurant guide, highlights the area's burgeoning restaurant scene. Events are also listed in the Washington Heights & Inwood Online calendar.[54]

Nearby to Hudson Heights lies the United Palace, a church, live music venue, and non-profit cultural center located at 4140 Broadway between West 175th and 176th Streets. It was built in 1930 as Loew's 175th Street Theatre, a movie palace – one of five Loews had in New York City – designed by architect Thomas W. Lamb. Its lavishly eclectic interior decor was supervised by Harold Rambusch.[55][56][57][58] The theater originally presented films and live vaudeville and operated continuously until closed by Loew's in 1969. That same year it was purchased for over a half million dollars by the television evangelist Rev. Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II, better known as Reverend Ike. The theater became the headquarters of his United Church Science of Living Institute and was renamed the Palace Cathedral. It was completely restored and still continues to be maintained by the United Church.[59] The building was designated a New York City landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on December 13, 2016.[60]

Police and crime[edit]

Hudson Heights, along with Inwood, is patrolled by the 34th Precinct of the NYPD, located at 4295 Broadway.[61] The 34th Precinct ranked 23rd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010.[62]

The 34th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 86.3% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 1 murder, 27 rapes, 200 robberies, 315 felony assaults, 155 burglaries, 592 grand larcenies, and 87 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[63]

Fire safety[edit]

Hudson Heights is served by the New York City Fire Department (FDNY)'s Engine Company 93/Ladder Company 45/Battalion 13, located at 515 West 181st Street.[64][65]

Post office and zip codes[edit]

Hudson Heights is located in two ZIP Codes. The area south of 187th Street is part of 10033 while the area north of 187th Street is part of 10040.[66]

The United States Postal Service operates two post offices near Washington Heights: the Washington Bridge Station at 518 West 181st Street[67] and the Ft George Station at 4558 Broadway.[68]

Religion[edit]

The Hebrew Tabernacle of Washington Heights is a Reform synagogue located at 551 Fort Washington Avenue, corner of 185th Street, in the neighborhood.[69][70][71] It is across from Bennett Park on West 185th Street.[72] It is Art Deco, with a bold and chalky limestone facade, with stainless steel and brass.[72][73] The Hebrew Tabernacle Congregation purchased the building in 1973, and it became a synagogue. The Hebrew Tabernacle Congregation, founded in 1905 in Harlem by German-Jewish founders, had outgrown its 1920s building on West 161st Street between Broadway and Fort Washington Avenue, and the Jewish congregants there were becoming increasingly isolated.[74][75][76] As of 1982,[update] many of the synagogue's members had come to New York in the 1930s as Jewish refugees from central Europe (so many German Jews were in the neighborhood, that it was jokingly referred to as "Frankfurt on the Hudson"), and it had 500 families as members.[77][78] It is a member of the Union for Reform Judaism.[69]

The Roman Catholic patron saint of immigrants, Mother Francesca Saverio Cabrini, is entombed at her shrine near the northern end of Fort Washington Avenue. Cabrini, America's first saint, was beatified in November 1938 and canonized in July 1946. She founded the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The name of the street on the west side of the school and shrine was changed in 1938 from Northern Avenue to Cabrini Boulevard.[79]

Washington Heights is also the home of Khal Adath Jeshurun (KAJ or "Breuer's"), the German-Jewish Ashkenazi congregation established in the late 1930s.[80] The congregation maintains the German-Jewish mode of worship, its liturgy, practices, and distinctive melodies. There are several educational institutions associated with KAJ as well.

Other churches and synagogues in the area include Our Saviour's Atonement Lutheran Church; Congregation Mount Sinai Anshe; Uptown Community Church; Beth Am, The People's Temple; Fort Washington Collegiate Church; Fort Tryon Jewish Center; Holyrood Church; and Congregation Shaare Hatikvah Ahavath Torah v'Tikvoh Chadoshoh.

Education[edit]

Schools[edit]

For grades kindergarten through 8, Hudson Heights is zoned to the New York City Department of Education's P.S./I.S. 187 Hudson Cliffs; it had 796 students as of the 2016–2017 school year.[update][81] In 2013, 43% of the school's third grade students met state standards in English, as opposed to 28% in the entire city.[8] The School Quality Snapshot of 2016–17 showed that 51% of the school's students met the state's standards in both English and Math, which compares favorably to citywide figures of 41% in English and 38% in Math.[9]

Another public school in the extended definition of the neighborhood is P.S. 173, located on Fort Washington Avenue between West 173 and 174th Streets, which includes grades pre-K through 5. P.S. 173's state test scores show that 34% met state standards in English, as opposed to 40% citywide, and 37% met the Math standards, compared to 42% in the city as a whole.[9]

Also located in the neighborhood was the Roman Catholic Mother Cabrini High School, which closed at the end of the 2013–14 school year;[82] the building is now a Success Academy Charter School.[83]

Private schools in the general area, including nearby Inwood, include Osher Early Learning Center;[84] the Medical Center Nursery School;[85] the YM/YWHA of Washington Heights and Inwood Nursery School;[86] and the City College Academy of the Arts,[87] a project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.[8]

Library[edit]

The nearest New York Public Library (NYPL) branch is the Fort Washington branch, located at 535 West 179th Street. The three-story Carnegie library opened in 1979.[88]

Hospitals[edit]

The neighborhood has no local hospitals. The former St. Elizabeth's Hospital at 689 Fort Washington Avenue at West 190th Street has now been converted into cooperative apartments. The nearest hospitals are Allen Hospital at the northernmost tip of Manhattan, and Columbia University Medical Center at West 169th Street, both part of the New York-Presbyterian system.

Transportation[edit]

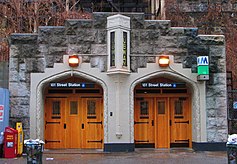

Both of the subway entrances in Hudson Heights are notable. The subway entrance at Fort Washington Avenue and West 193rd Street, which leads to the 190th Street station on the A service, is the only New York City Subway entrance in the Gothic style; although when originally built, it was a plain brick building: the stone façade was added later to bring the building into harmony with the entrance to Fort Tryon Park just across Margaret Corbin Circle.[89] The station was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. The station also has the distinction of being one of the deepest in the entire subway system by distance to ground level.[90] The 184th Street entrance of the 181st Street station, served by the A train as well, also stands out among entrances to the city's subway stations.[91]

Both of the stations provide elevator connections between Hudson Heights, on the top of the ridge, and the Broadway valley of Washington Heights below. The 190th Street station elevators lead to the entrance at Bennett Avenue north of West 193rd Street, and the 184th Street elevators go to Overlook Terrace and 184th Street. When originally built, fare control for both of these entrances were in the station house, outside the elevators, which meant that they could only be used by paying a subway fare, but both have had fare control moved down to the mezzanine level, making the elevators free for neighborhood residents to use, and providing easier pedestrian connection between Hudson Heights and the rest of Washington Heights.[89]

The George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal, at West 179th Street and Fort Washington Avenue, was designed by the Italian architect and economist Pier Luigi Nervi and constructed in 1963. From a distance, the huge ventilation ducts look like concrete butterflies.[92] Nervi's bust sits in the terminal's lobby. The station has been undergoing a renovation and is expected to re-open in the summer of 2015. Over 100,000 square feet of new shops will be included in the updated station.[8]

The George Washington Bridge, visible for miles from its entrance at 179th Street, earns this accolade from the noted architect Le Corbusier:

The George Washington Bridge over the Hudson is the most beautiful bridge in the world. Made of cables and steel beams, it gleams in the sky like a reversed arch. It is blessed. It is the only seat of grace in the disordered city.[93]

Beneath the bridge, at the east stanchion, is the Little Red Lighthouse, where a namesake festival is held is in the late summer, and where a 5.85-mile (9.41 km) recreational swim finishes in early autumn.[94] It is also a popular place to watch for peregrine falcons[95] and the monarch butterfly migration.[96]

Streets[edit]

The primary north–south streets in Hudson Heights are:

- Fort Washington Avenue – named after Fort Washington, the last fortified position of the Continental Army in New York before the city was taken over by the British in the American Revolutionary War.[97]

- Pinehurst Avenue – named after "Pinehurst", the estate of sheepskin manufacturer C. P. Bucking[98][17]

- Cabrini Boulevard – formerly "Northern Avenue", the street was renamed in 1938 for Mother Cabrini, who was later canonized by the Roman Catholic Church.[79]

- Overlook Terrace – which runs at the bottom of the ridge from West 190th to 184th Street, was named for the view at the top of the street, before it descends[99]

- Bennett Avenue – which runs at the bottom of the ridge east of Overlook Terrace from Nagle Avenue to West 181st Street. It was named after James Gordon Bennett, Sr., who founded the New York Herald newspaper. His name is also enshrined on Bennett Park in the heart of the neighborhood.[100]

Other named or co-named streets in the neighborhood include:

- Alex Rose Place (West 186th Street between Chittenden Avenue and Cabrini Boulevard) – Rose was a milliner born in Warsaw in 1898 who became president of the United Hatters, Cap & Millinery Workers Union, and was a founder in 1944 of the Liberal Party of New York. Rose was considered to be a political kingmaker, and helped Fiorello H. LaGuardia and John Lindsay to reach office as Mayors of New York City. Rose lived at 200 Cabrini Boulevard nearby.[101]

- Chittenden Avenue – named in 1911 after Lucius Chittendon, a merchant from New Orleans[16] and the owner of the land between West 185th to 198th Streets. The street runs from West 186th to 187th Street, just west of Cabrini Boulevard.[102] Since the Henry Hudson Parkway runs almost directly below it, there are no buildings on the west side of the street, which therefore provides expansive views of the George Washington Bridge and the Palisades.

- Colonel Robert Magaw Place – named after Col. Robert Magaw, a lawyer from Philadelphia who commanded the American forces in Fort Washington during the Battle of Fort Washington. The street runs for two blocks from West 181st to 183rd Streets, east of Fort Washington Avenue and west of Bennett Avenue.[103]

- Jacob Birnbaum Way (portion of Cabrini Boulevard at West 187th Street) – named after Jacob Birnbaum, a human rights advocate born in Germany, and the founder in 1964 of Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, as well as other organizations. He lived at Cabrini and West 187th Street. The section of street was named after him on October 18, 2015.[104]

- Margaret Corbin Circle and Margaret Corbin Drive – The circle is outside the main entrance to Fort Tryon Park, while the drive runs from there through the park to the Henry Hudson Parkway. Both are named after Margaret Corbin, a heroine of the American Revolution who took her husband's place in a cannon crew after he was killed,[105] and subsequently the first female pensioner of the United States. Her annual pension was a suit of clothes and cash equivalent to the cost of a half-pint of liquor.[106]

- Paterno Trivium (intersection of Cabrini Boulevard, Pinehurst Avenue and West 187th Street) – named after Dr. Charles V. Paterno, a dentist-turned-real estate developer who built the Hudson View Gardens cooperative complex, and lived in a mansion known as "Paterno's Castle", on the site of what is now Castle Village, another one of his developments. The Trivium – Latin for the meeting of three streets – was designed by architect Thomas Navin, and was designated part of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation's "Greenstreets" program in 2000. It was formally dedicated on August 4, 2001, the birth date of Dr. Paterno. It features a small garden and benches for sitting.[107][108]

- Plaza Lafayette (West 181st Street between Cabrini Boulevard and Riverside Drive) – The original name of Riverside Drive was "Boulevard Lafayette", named after the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolution, and this small plaza retains the name.[109] An overlook on the west end of the plaza features views of the Henry Hudson Parkway, the George Washington Bridge, the Hudson River, and the Palisades.

Parks[edit]

Parks in Hudson Heights include:

- Fort Tryon Park – a large, 67 acres (27 ha) park assembled by John D. Rockefeller Jr., designed by the Olmsted Brothers and presented to the city in 1931. It is the site of The Cloisters, which houses the Medieval art collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Bennett Park – the site of Fort Washington during the Revolutionary War, is a neighborhood park named after James Gordon Bennett Sr., the publisher of the New York Herald. It is the location of the highest natural point in Manhattan.

- J. Hood Wright Park – which is included in the extended definition of the neighborhood, is located between Fort Washington and Haven Avenues, and between West 173rd and 176th Streets. It is a neighborhood park named for James Hood Wright, a banker, financier and philanthropist, and includes a recreation center.

- Fort Washington Park – runs along the Hudson River from West 155th Street to Dyckman Street, under the George Washington Bridge. It includes the Little Red Lighthouse.

Notable residents[edit]

Notable current and former residents of Hudson Heights include:

- C. K. G. Billings, industrialist, avid horseman and eccentric tycoon; his estate, Tryon Hall, formed the basis for Fort Tryon Park

- Jacob Birnbaum, activist for the rights of Soviet Jews[104]

- Rabbi Joseph Breuer, religious leader[110]

- Mother Francesca Saverio Cabrini, missionary, saint, and namesake of the neighborhood High School, Shrine, Boulevard and Woods[111]

- Laurence Fishburne, actor[112]

- Scott Goldstein, writer, producer, director

- Henry Kissinger (born 1923), diplomat and statesman[113]

- Daniel D. McCracken, early computer pioneer, City College of New York professor, and author

- Lin-Manuel Miranda, playwright, actor, and musician, owns two co-op units in the Castle Village complex in Hudson Heights.[114]

- Charles V. Paterno, a doctor who became a real estate developer, he built Hudson View Gardens and Castle Village, two of the largest complexes in the neighborhood, the latter on the site of his own mansion, which was known as "Paterno's Castle".[107][108] The Paterno Trivium at the intersection of Cabrini Boulevard, Pinehurst Avenue and West 187th Street is named for him.[115]

- Alex Rose, labor leader[101]

- James R. Russell, scholar of Ancient Near Eastern, Iranian and Armenian Studies, and Harvard University professor

- Rabbi Shimon Schwab, religious leader[116]

- Dr. Ruth Westheimer (born 1928), better known as Dr. Ruth, German-American sex therapist, talk show host, author, professor, Holocaust survivor, and former Haganah sniper.[117]

In popular culture[edit]

The 1985 film We Were So Beloved tells the stories of neighborhood Jews who escaped the Holocaust.[118] A musical that began performances in 2007, In The Heights, takes place on 181st Street and Fort Washington Avenue, and was written and produced by Lin-Manuel Miranda who grew up in northern Manhattan.[119][120] The same year, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, a novel by Junot Diaz, referred to Anglo women carrying yoga mats in the neighborhood as a harbinger of gentrification; the book won the Pulitzer Prize for letters in 2008.[121]

Gallery[edit]

-

The Fort Tryon Park Cottage is a remnant of one of the estates which abounded in the area

-

Nine flights of stairs connect Overlook Terrace and Fort Washington Avenue at West 187th Street

-

The 181st Street subway entrance between West 183rd and 185th Streets provides elevators which lead to...

-

...the entrance at 184th Street and Overlook Terrace in the Broadway valley of Washington Heights below

-

The former St. Elizabeth's Hospital is now cooperative apartments

-

The entrance to 186-196 Pinehurst Avenue

References[edit]

Informational notes

- ^ Neighborhoods in New York City do not have official status, and their boundaries are not specifically set by the city. (There are a number of Community Boards, whose boundaries are officially set, but these are fairly large and generally contain a number of neighborhoods, and the neighborhood map issued by the Department of City Planning only shows the largest ones.) Because of this, the definition of where neighborhoods begin and end is subject to a variety of forces, including the efforts of real estate concerns to promote certain areas, the use of neighborhood names in media news reports, and the everyday usage of people.

Citations

- ^ Orenstein, Sidney (February 27, 2017) "The Geology of Northern Manhattan" (lecture)

- ^ "Bennett Park" New York City Parks and Recreation Department website. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Kuhn, Jonathan. "Fort Tryon Park" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ a b Staff (September 17, 2001) "Manhattan apartments at a discount: Hudson Heights" New York

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (October 16, 2009) Map included in "An Aerie Straight Out of the Deco Era" The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Wisloski, Jess (February 14, 2004) "Close-Up on Hudson Heights" The Village Voice. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ "Hot Guide 2009. Hudson Heights: 173rd Street to Fort Tryon Park, West of Broadway" Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hughes, C. L. (October 15, 2014) "Affordable Manhattan in Hudson Heights" The New York Times

- ^ a b c d Jacobsen, Aileen (March 28, 2018) "Living In: Hudson Heights: A Hidden Gem, Gaining Popularity" The New York Times

- ^ "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.448

- ^ "The Battle of Fort Washington, Revolutionary War" Archived February 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine on AmericanRevolution.org

- ^ Jenkins, Stephen (1911) The Greatest Street in the World: The Story of Broadway, Old and New, from the Bowling Green to Albany, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p.36

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.232

- ^ a b c Renner, James (2007) Images of America: Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing.

- ^ a b c Feirstein, p.170

- ^ a b Norcross, Frank Wayland (1901) A History of the New York Swamp Chiswick Press. p.208

- ^ Staff (January 4, 1917) "C.K.G. Billings Sells Famous Tryon Hall: Prominent New Yorker, Whose Name is Withheld, Buys Riverside Drive Estate; Mansion Cost $2,000,000 – Built on Site of Fort of Revolutionary Frame, the House is One of New York's Show Places", The New York Times p.22. Accessed June 4, 2009

- ^ Renner, James. "C.K.G. Billings" Archived April 18, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, on the Hudson Heights Owners Coalition website Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ Van Dine, S.S. (1934) The Dragon Murder Case. New York: Charles Scribner's.

- ^ a b c Lowenstein (1989), pp.42–44

- ^ a b Bennet, James (August 27, 1992) "The Last of Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson: A Staunch, Aging Few Stay On as Their World Evaporates" The New York Times

- ^ Lowenstein (1989), p.18

- ^ a b Hendrickson, Leslie (October 18, 2007) "Hudson Heights Climbing to the Next Level" New York Sun

- ^ Ressig, Volker. Frankfurt on the hudson, oder: Die Liebe für Amerika, die Sehnsucht für Europa Archived December 2, 2005, at the Wayback Machine (Trans.: "Frankfurt on the Hudson, Or: The love for America, the longing for Europe.") Körber-Stiftung.

- ^ "Inwood/Washington Heights" Archived October 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Immigrant Heritage Trail

- ^ "A Jewish Journal Reborn in Berlin" Archived November 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine German Embassy in Washington, D.C

- ^ Lowenstein (1989), p.51

- ^ Blake, Maria (July/August 2008) "Second Life." Columbia Journalism Review, Vol. XLVII, No. 2, p.12.

- ^ Aufbau, Das Jüdische Monatsmagazin

- ^ "Washington Heights" Columbia 250

- ^ White, et al., p.571

- ^ a b Calabi, Marcella and Ritter, Elizabeth Lorris (October 29, 2010) "How Hudson Heights Got Its Name" Archived August 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Hudson Heights Guide

- ^ Garb, Maggi (November 8, 1998) "If You're Thinking of Living In Hudson Heights: High Above Hudson, a Crowd of Co-ops", The New York Times

- ^ "Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000; Census Tract 273, New York County, New York, Language Spoken at Home" Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 4, 2009; and "Profile of Selected Social Characteristics: 2000; Census Tract 275, New York County, New York, Language Spoken at Home" Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today United States Census Bureau Accessed June 4, 2009

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (October 16, 2009) "Living in Hudson Heights: An Aerie Straight Out of the Deco Era". The New York Times Accessed March 7, 2010.)

- ^ Arak, Joey (April 8, 2011) "How to Gentrify a Neighborhood: Just Study Hudson Heights" Curbed New York

- ^ Mokha, Kavita Mokha (April 8, 2011) "Hudson Heights Pumps More-for-Less Theme" The Wall Street Journal. Accessed April 13, 2011.

- ^ Eligon, John (April 22, 2008) "In Hudson Heights, A Bid to Keep the Economy's Woes from Becoming Their Own", The New York Times. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ Schlesinger, Toni (January 1, 2002) "NY Mirror: Studio in Hudson Heights", The Village Voice. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Staff (November 2007) "New York – Best Place to Retire: Hudson Heights" Money

- ^ a b Diaz, Junot (September 2007) "He'll Take El Alto" Gourmet. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ Platt, Russell (May 16, 2016) "Romanesque Riffs" The New Yorker. Accessed May 28, 2016.

- ^ "History of The Pinehurst" Archived March 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine on Pinehurst Co-Operative Apartments website. Retrieved May 28, 2016

- ^ "Paterno Trivium" New York City Parks and Recreation Department website

- ^ "NYC Department of Buildings Inquiry Report: Castle Village Retaining Wall Collapse April 2007" Archived May 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine New York City Department of Buildings website Retrieved June 23, 2010

- ^ Solomonow, Seth (February29, 2008) "181st Street Ramp to Reopen on Saturday, March 1" New York City Department of Transportation. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ Cohen, Joyce (July 31, 2005) "The Hunt: Moving Forward Without Moving Too Far"[permanent dead link] New York Times, Section 11, p.6. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ Hudson Heights Owners Coalition. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- ^ "Cabrini Terrace Cooperative Apartments" Archived May 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine on the Hudson Heights Owners Coalition website (December 23, 1999) Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ Dwyer, James (January 23, 2008) "(Solar) Power to the People Is Not So Easily Achieved" The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2008

- ^ The 2007 Medieval Festival in Fort Tryon Park, The Washington Heights and Inwood Development Corporation Archived September 10, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Uptown Art Stroll website Accessed June 4, 2009

- ^ "Calendar" Archived December 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine on Washington Heights & Inwood Online

- ^ Adams, Nathaniel (January 15, 2015). "Across the New York Area, Restoring 'Wonder Theater' Movie Palaces to Glory". The New York Times.

- ^ .Dunlap, David W. (April 13, 2001), "Xanadus Rise to a Higher Calling", The New York Times

- ^ Atamian, Christopher (November 11, 2007). "'Rite of Spring' as Rite of Passage". The New York Times.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12543-7., p.286

- ^ Lehman-Haupt, Christopher. (July 30, 2009) "Reverend Ike, Who Preached Riches, Dies at 74" The New York Times

- ^ Staff (December 13, 2016) "LPC Backlog Initiative Results in 27 New Landmarks" (press release) New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- ^ "NYPD – 34th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Inwood – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "34th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Engine Company 93/Ladder Company 45/Battalion 13". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Washington Heights, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Washington Bridge". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Fort George". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Hebrew Tabernacle Bulletin, January–February 2019

- ^ Sibylle Quack (2002). Between Sorrow and Strength; Women Refugees of the Nazi Period, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Moses Rischin, Raphael Asher (1991). The Jewish Legacy and the German Conscience; Essays in Memory of Rabbi Joseph Asher

- ^ a b David W. Dunlap (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion; A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Norval White, Elliot Willensky, Fran Leadon (2010). AIA Guide to New York City, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Robert W. Snyder (2014).Crossing Broadway; Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City, Cornell University Press.

- ^ Kerry M. Olitzky, Marc Lee Raphael (1996). The American Synagogue; A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein (1989). Frankfurt on the Hudson; The German-Jewish Community of Washington Heights, 1933–1983, Its Structure and Culture, Wayne State University Press.

- ^ "Hebrew Tabernacle Marking 75th Anniversary". The New York Times. May 2, 1982.

- ^ Crowns, Crosses, and Stars; My Youth in Prussia, Surviving Hitler, and a Life Beyond

- ^ a b Moscow, p. 38

- ^ "History" Archived September 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on the Khal Adath Jeshrun website. Accessed August 31, 2001

- ^ "P.S./I.S. 187 Hudson Cliffs – M187". New York City Department of Education. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Chiwaya, Nigel (January 14, 2014) "Mother Cabrini High School to Close at End of School Year" Archived December 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine DNAinfo New York

- ^ Feeney, Michael J. (May 22, 2014) "Upper Manhattan parents fuming over Success Academy securing a school building in their district" New York Daily News

- ^ See the Osher Early Learning Center website

- ^ See the Medical Center Nursery School website

- ^ See the YM/YWHA of Washington Heights and Inwood Nursery School website

- ^ See the City College Academy of the Arts Archived December 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine website

- ^ "About the Fort Washington Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Guided tour (October 11, 2014) Fort Tryon Park Cottage

- ^ "The Deepest and Highest Subway Stations in NYC: 191st St, 190th Street, Smith & 9th" on Untapped Cities (June 26, 2013)

- ^ "Down In the Hole, Forgotten NY Subways & Trains" on Forgotten New York

- ^ White et al., p.570

- ^ Corbusier, Le (1947) Le Corbusier in America: When the Cathedrals were White New York: Reynal and Hitchcock.

- ^ "Little Red Lighthouse Swim, Manhattan Island Foundation". Archived from the original on September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Fort Washington Park: Peregrine Falcons in New York City", New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website

- ^ "Monarch Butterflies In New York City" Informational marker in Fort Washington Park

- ^ Moscow, p.51

- ^ Moscow, p.84

- ^ Moscow, p.80

- ^ Moscow, p.28

- ^ a b Feirstein, p.169

- ^ Moscow, p.38

- ^ Moscow, p.71

- ^ a b Zalman, Jacob (October 23, 2015) Jonathan Zalman, "New York City Street Dedicated to Soviet Jewish Activist Jacob Birnbaum" The Tablet

- ^ Moscow, p.75

- ^ Feirstein, p.173

- ^ a b Parks Department informational sign on site. Accessed: March 8, 2017

- ^ a b "Greenstreet: Highlights – Paterno Trivium" New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website

- ^ Feirstein, p.174

- ^ Bodenheimer, Dr. Ernst J. with Scherman, Rabbi Nosson (April 27, 2009) "Rabbi Yoseph Breuer: The Rav of Frankfurt, U.S.A., On His 29th Yahrtzeit, Today, 3 Iyar" matzav.com

- ^ Luongo, Michael (February 6, 2015) "In Upper Manhattan, Restoring the Golden Halo of Mother Cabrini" The New York Times

- ^ Staff (March 7, 2008) "Hudson Heights delivers", New York Daily News Accessed March 20, 2008

- ^ Suri, Jeremi (2007) Henry Kissinger and the American century Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674025792. p.44

- ^ "Lin-Manuel Miranda Reveals Location of His First Post-College NYC Apartment | StreetEasy". November 5, 2018.

- ^ "GREENSTREET Highlights – Paterno Trivium : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org.

- ^ Schwab, Shimon & Schwab, Moshe (2001). Rav Schwab on Prayer. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications. ISBN 1-57819-512-8.

- ^ Morris, Bob. (December 21, 1995) "At Home With: Dr. Ruth Westheimer; The Bible as Sex Manual?" The New York Times

- ^ Canby, Vincent (August 27, 1986) "Film Review: 'We Were So Beloved'" The New York Times

- ^ "In the Heights" Archived August 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine on the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- ^ "In the Heights" on the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ "Columbia University School of Journalism, Pulitzer Prizes for Letters". Accessed June 4, 2009

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Places & How They Got Their Names. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2712-6.

- Lowenstein, Steven M. (1989) Frankfurt on the Hudson: The German Jewish Community of Washington Heights, 1933–1983, Its Structure and Culture Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814319602

- Moscow, Henry (1978). The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. New York: Hagstrom Company. ISBN 978-0-8232-1275-0.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

External links[edit]

Media related to Hudson Heights, Manhattan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hudson Heights, Manhattan at Wikimedia Commons