Holy Cross Cemetery (Colma, California)

| Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery | |

|---|---|

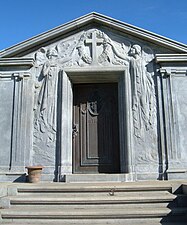

Holy Cross Mausoleum | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1887 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 37°40′16″N 122°26′43″W / 37.671155°N 122.445191°W |

| Type | Catholic |

| Owned by | Archdiocese of San Francisco |

| Size | 300 acres (1.2 km2) |

| Website | Holy Cross Cemetery |

| Find a Grave | Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery |

| The Political Graveyard | Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery |

Holy Cross Cemetery (Spanish: Cementerio de la Santa Cruz)[1][2] is a Roman Catholic cemetery in Colma, California, operated by the Archdiocese of San Francisco. Established in 1887 on 300 acres (1.2 km2), it is one of the oldest and largest cemeteries in California.

History[edit]

Calvary Cemetery in San Francisco was consecrated in 1860 by the first Archbishop of San Francisco, Joseph Sadoc Alemany.[3]: 27 Nearly thirty years later, Cavalry had nearly reached its capacity and Alemany's successor, Patrick William Riordan, purchased 179 acres (72 ha) of land in nearby San Mateo County.[4]: 13 Alemany's successor, Patrick William Riordan, blessed the initial 25-acre (10 ha) Holy Cross site on June 3, 1887, as the first cemetery in Colma.[3]: 24 The first burials were conducted on June 7; Timothy Buckley's funeral carriage arrived just before Elizabeth Martin's.[5] That year, the Southern Pacific Railroad completed a branch track to Holy Cross.[6] The Holy Cross site was deliberately left unconsecrated because of the possibility the cemetery may be relocated again.[3]: 62 The site now covers 283 acres (115 ha).[4]: 13

The Old Lodge Building, used as offices, were completed in 1902 to a design by Frank and William Shea, across Mission from the main entrance to the cemetery (1595 Mission Road); they also designed the stone-topped cemetery entry gates. These structures feature sandstone fascia in the Richardsonian Romanesque Revival style.[4]: 282–286 It is nicknamed "McMahon's Station" after a hotel built by the brothers Owen and Patrick McMahon at the same site, which was destroyed by fire in January 1894,[7] rebuilt,[8] and destroyed again by fire in September 1897.[3]: 66 [9] Additional offices were completed in 1956, east of El Camino Real.[4]: 316

The large mausoleum at Holy Cross was designed by John McQuarrie and dedicated on March 28, 1921 by Archbishop Edward Joseph Hanna. It has been expanded since its opening and contains room for 40,000 crypts, covering 9 acres (3.6 ha).[3]: 62 The Archbishops of San Francisco are interred in crypts within the mausoleum's rotunda.[3]: 62–63 There are two smaller mausoleums on the site: All Saints, in the property's south corner (near Lawndale and Mission) and Saints Peter and Paul, a garden court (outdoor mausoleum) near the north corner.[3]: 64

After the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a measure in March 1900, banning future burials within city limits effective August 1, 1901, the development of Colma as the city's necropolis began in earnest, eventually culminating in the eviction of the existing cemeteries.[3]: 35 Many of the people interred at the Catholic Calvary Cemetery were reburied between 1937 and 1945 at Holy Cross in a project to relocate graves outside of the city.[10][11] There is a memorial sculpture at Holy Cross erected in 1993 to mark the moved remains,[3]: 44 which features three crosses and reads: "Interred here are the remains of 39,307 Catholics moved from Mt. Calvary Cemetery in 1940 and 1941 by order of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Rest in God's Loving Care."[12]

After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, it was estimated that 3⁄4 of the monuments at Holy Cross were toppled or thrown askew, including large ornamental stone balls atop the entry gates.[3]: 45–46 The subsequent 1957 Daly City earthquake damaged the cemetery again.[3]: 48

A Googie-styled circular Receiving Chapel complex was designed by Frank W. Trabucco[13] and completed in 1963; it contains five separate chapels, each decorated with murals by Thomas Lawless. The current chapel replaced an older chapel at the same site, completed in 1914.[3]: 63–65

-

Holy Cross Cemetery shortly after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

-

Archbishops' Crypt, Holy Cross Mausoleum

-

Holy Cross Receiving Chapel (completed 1963)

-

Relocation memorial

-

Stone-topped gate pillar on Mission Road, completed in 1902

-

Lawn and mausoleum

Two of the cemetery sequences from the film Harold and Maude, in which Harold attends the funerals of strangers and meets Maude, were filmed at Holy Cross[14] in Sections T[15] and J;[16] the Mausoleum and Hillside Boulevard gate also appear in the film.[17] Additional sequences were filmed at nearby cemeteries in Colma and San Bruno, including Cypress Lawn, Woodlawn,[3]: 12 and Golden Gate National Cemetery.[18]

Notable burials[edit]

-

Beniamino Bufano grave

-

Joseph Cuneo mausoleum

-

Joe DiMaggio grave

-

Dunphy-Carmen family vaults

-

Lynch family vault

-

M. H. de Young mausoleum

Several notable people are buried at Holy Cross, including former politicians, and people of the California Gold Rush.

This cemetery also contains one British Commonwealth war grave, of a Canadian Infantry soldier of World War I.[19]

A[edit]

- Joseph Alemany, San Francisco's first archbishop

- Joseph Alioto, Mayor of San Francisco (1968-1976)

- Pedro Altube, rancher

- Delos R. Ashley, Nevada U.S. Representative

B[edit]

- Winifred Bonfils, reporter and columnist

- Jimmy Britt, boxer

- Pat Brown, 32nd Governor of California

- Benny Bufano, sculptor

C[edit]

- Joe Carcione, "The Green Grocer" columnist and personality

- Eugene Casserly, U.S. Senator

- John Chapman, Civil War soldier, Medal of Honor recipient

- Joe Corbett, Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher

- Frank Crosetti, New York Yankees MLB player, teammate of Joe DiMaggio

D[edit]

- Joe DiMaggio (1914–1999), MLB player, Hall of Fame member[20]

- John G. Downey, 7th Governor of California

E[edit]

- Eddie Erdelatz, first head coach of Oakland Raiders football team

F[edit]

- James Graham Fair, Bonanza King, U.S. Senator

- Cy Falkenberg, baseball player[21]

- Abigail Folger, Heiress, socialite, Manson murder victim

- Edwin Alexander Forbes, Adjutant-General of California

- Kathryn Forbes, writer

- Tirey L. Ford, Attorney-General for California

- Charlie Fox, MLB manager, coach, and scout

G[edit]

- Oliver Gagliani (1917–2002) photographer, and educator

- A.P. Giannini, founder of Bank of America

- Charlie Geggus, MLB player, who played one season for the 1884 Washington Nationals of the Union Association

- Vince Guaraldi, jazz musician known for composing music for animated television adaptations of the Peanuts comic strip including their signature melody, "Linus and Lucy"

H[edit]

- Edward Joseph Hanna, San Francisco's Third Archbishop

- Michael A. Healy, American Captain in United States Revenue Cutter (predecessor of the United States Coast Guard)

- William Edward Hickman, American convicted murderer

- Edward Higgins, General of the Salvation Army

- Eric Hoffer, American moral and social philosopher

I[edit]

- Samuel Williams Inge, U.S. Representative for Alabama

K[edit]

- Paul Kantner, guitarist for Jefferson Airplane

- George Kelly, MLB Hall of Famer

L[edit]

- Bill Lange, MLB player for Chicago Cubs (1893–1899)

- William Joseph Levada, San Francisco's Seventh Archbishop, Prefect emeritus of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (elevated to Cardinal in 2006)

M[edit]

- Ralph Maradiaga (1934–1985), Chicano artist, printmaker, muralist

- Leo McCarthy, former California Lieutenant Governor

- Pete McDonough, bail bondsmen

- James A. McDougall. U.S. Senator

- Joseph Thomas McGucken, San Francisco's Fifth Archbishop

- Theresa Meikle, first woman elected to Superior Court Judge in a major American city

- John J. Mitty, San Francisco's Fourth Archbishop

- John J. Montgomery, pioneer aviator, aerodynamicist, and physicist; first American to fly in a heavier-than-air machine

- Maggie Moore, silent film actress

- George Moscone, Mayor of San Francisco

N[edit]

- George Hugh Niederauer, San Francisco's Eighth Archbishop

- John I. Nolan, U.S. Representative

- Mae Nolan, California's first female congressperson

O[edit]

- William S. O'Brien, Bonanza King

- Bryan O'Byrne, actor

- M.M. O'Shaughnessy, San Francisco city engineer

P[edit]

- James D. Phelan, Mayor of San Francisco, U.S. Senator

- Ralph Pinelli, MLB player

Q[edit]

- John Raphael Quinn, San Francisco's Sixth Archbishop

R[edit]

- Patrick William Riordan, San Francisco's Second Archbishop

- Angelo Joseph Rossi, Mayor of San Francisco (1931–1944)

- Pietro Carlo Rossi, wine maker and first President Italian Swiss Colony

- Charles M. Rousseau (1848–1918) Kingdom of Belgium-born American architect[22]

- Oliver Rousseau (1891–1977), American architect, home builder/contractor, and real estate developer

S[edit]

- Hank Sauer, MLB player

- Eugene Schmitz, Mayor of San Francisco (1902–1907)

- Fred Scolari, professional basketball player

- John F. Shelley, Mayor of San Francisco (1964–1968)

- William M. Stewart, U.S. Senator

- James Joseph Sweeney, First bishop of Diocese of Honolulu

T[edit]

- Ethel Teare, American silent film actress

W[edit]

- Richard J. Welch, U.S. Representative

- Kaisik Wong, fashion designer

- William J. Wynn, U.S. Representative

Y[edit]

- Michael de Young, co-founder of the San Francisco Chronicle, namesake of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum.

Z[edit]

- Frank Zupo, MLB player with the Baltimore Orioles

References[edit]

- ^ Arquidiócesis de San Francisco - Cruzada Guadalupana

- ^ San Francisco Católico - Noviembre 17, 2019

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Svanevik, Michael; Burgett, Shirley (1995). City of Souls: San Francisco's Necropolis at Colma. San Francisco, California: Custom & Limited Editions. ISBN 1-881529-04-5.

- ^ a b c d Shoup, Laurence H.; Brack, Mark; Fee, Nancy; Giberti, Bruno (June 1994). A Historic Resources Evaluation Report of Seven Colma Cemeteries (Report). BART–San Francisco Airport Extension Project. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Bartlett, Jean (October 12, 2011). "The grave side of history with Professor Michael Svanevik at nearby Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery". Pacifica Tribune. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "The Departed Year". Times Gazette. 7 January 1888. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Colma". Times Gazette. 20 January 1894. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Colma". Times Gazette. 25 August 1894. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "South San Francisco jottings". Times Gazette. 25 September 1897. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Svanevik, Michael; Burgett, Shirley (2017-05-17). "Matters Historical: How dead San Franciscans were moved to Colma". The Mercury News. ISSN 0747-2099. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Kastler, Deanna L. (2010-07-22). "Cemeteries". Encyclopedia of San Francisco. SF Museum and Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2010-07-22. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Branch, John (2016-02-05). "The Town of Colma, Where San Francisco's Dead Live". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ^ "Trabucco, Frank W." SF Gate. July 4, 2003. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (2018-05-30). "'Harold and Maude': meeting cute at a funeral". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ "Harold and Maude - At the Cemetery - 1". ReelSF. April 12, 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Harold and Maude - At the Cemetery - 2". ReelSF. August 16, 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Meretzky, Steve (2013). "The cemetery where Maude steals Harold's hearse". The Harold and Maude Project. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Harold and Maude - Sunflowers and Daisies". ReelSF. March 27, 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ [1] CWGC casualty record.

- ^ Mino-Bucheli, Sebastian (October 7, 2021). "Some of the Most Famous People Buried in Colma (With Map)". KQED.

- ^ Enders, Eric. "Cy Falkenberg". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Rousseau". San Francisco Chronicle. 1918-11-17. p. 12. ISSN 1932-8672. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Holy Cross Cemetery, Colma – interment.net