Hossein Borujerdi

Hossein Borujerdi | |

|---|---|

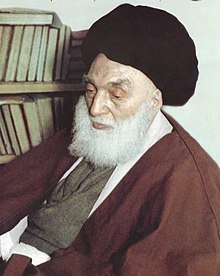

Borujerdi, late 1950s | |

| Title | Grand Ayatollah |

| Personal | |

| Born | 23 March 1875 |

| Died | 30 March 1961 (aged 86) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Era | Modern history |

| Creed | Usuli Twelver Shia Islam |

| Main interest(s) | uṣūl al-fiqh |

| Muslim leader | |

| Based in | Najaf, Iraq |

| Period in office | 1937–1946 |

| Predecessor | Abu l-Hasan al-Isfahani |

| Successor | Muhsin al-Hakim |

| Post | Grand Ayatollah |

Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Hossein Ali Tabatabaei Borujerdi (Luri/Persian: آیت الله العظمی سید حسین طباطبایی بروجردی; 23 March 1875 – 30 March 1961) was a leading Iranian Shia Marja' in Iran from approximately 1947 to his death in 1961.[1]

Life[edit]

Borujerdi was born on 23 March 1875 in the city of Borujerd in Lorestan Province in Iran. His family traced its lineage 30 generations to Hassan ibn Ali (the grandson of Muhammad).[2] His father Sayyid Ali Tabataba'i was a religious scholar in Borujerd and his mother, Sayyidah Agha Beygum, was the daughter of Sayyid Mohammad Ali Tabataba'i.

Tenure as Ayatollah and Marja[edit]

Borujerdi revived the hawza of Qom in 1945 (1364 AH), which had waned after the death of its founder Abdul-Karim Ha'eri Yazdi in 1937. When Sayyid Abul Hasan Isfahani died the following year, the majority of Shi'a accepted Ayatullah Borujerdi as Marja'. Scholar Roy Mottahedeh reports that Borujerdi was the sole marja "in the Shia world" from 1945-6 until his death in 1961.[3]

Outreach in the Islamic world[edit]

Borujerdi was praised by Morteza Motahhari for attempting to bridge the gap between Sunnis and Shiites.[4] Borujerdi sent representatives to Lebanon, Kuwait, Sudan and Pakistan.[5] He also helped establish the Islamic Center of Hamburg.[5] Borujerdi also sent missionaries to spread Islam in Europe and the United States.[4]

He established cordial relations with Mahmud Shaltut, the grand Shaykh of Al-Azhar University.[5] Together, the two scholars established the "Organization for Rapprochement Among the Islamic Sects" ( Dar al-Taqrib bayn al-Madhahib al-lslamiyyah) in Cairo.[4] Shaltut issued a famous fatwa legitimizing Ja'fari school of jurisprudence on par with the four major Sunni legal schools, and promoted its teaching at Al-Azhar.[5]

Permission for narrating Hadith[edit]

Borujerdi was authorized as a Mujtahid by his teachers, which included Akhund Khurasani, Shaykh al-Shari'ah Isfahani and Sayyid Abu al-Qasim Dihkurdi. He was also given the permission of narrating Hadith by Akhund Khurasani, Shaykh al-Shari'ah Isfahani, Shaykh Muhammad Taqi Isfahani known as Aqa Najafi Isfahani, Sayyid Abu al-Qasim Dihkurdi, Agha Buzurg Tihrani and 'Alam al-Huda Malayiri.[6]

Teaching Method[edit]

Borujerdi used a simple language in his lessons and avoided unnecessary extra discussions. Like early Shi'a 'ulama such as Shaykh al-Mufid and Sayyid Murtada, Shaykh al-Tusi, Shaykh Tabarsi and Allamah Bahr al-'Ulum, he had a comprehensive knowledge of different Islamic studies. He also studied jurisprudential verdicts of Shi'a and Sunni faqihs of the past. He had a unique method in ‘Ilm al-rijal by studying the chain of narrators of hadiths in the Four Books independently from narrations. Through this method, he made great contributions to later research.[7]

Political leanings[edit]

Unlike many clergy and temporal rulers, Borujerdi and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, are said to have had cordial and mutually beneficial relations, starting with a visit by the Shah to Borujerdi's hospital room in 1944. Borujerdi is said to have generally remained aloof from politics and given the Shah his "tacit support," while the Shah did not follow his father's harsh anti-clericalism (for example he exempted clergy from military service), and until Borujerdi's death occasionally visited the cleric.[8][9]

Borujerdi's belief in quietism, or silence of state matters, extended to keeping silent in public on such issues as Israel's treatment of the Palestinians, the overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh and the end of his campaign to nationalize and control the British-owned oil industry in Iran, and the Baghdad Pact alliance with the US and UK.[10] It is thought that as a reward for this support the Shah ensured more religious instruction in state schools, tightened control of cinemas and other offensive secular entertainment during Moharram.

Ayatollah Borujerdi passively opposed the Pahlavi regime's agrarian reforms, which he called "agrarian destruction."[11] In his view, the confiscations of large concentrations of landholdings of aristocrats and clergy by the Pahlavi shahs disrupted the fabric of rural life and eroded religious institutions.

Ruhollah Khomeini, who would lead the Iranian people's revolution in 1979, was Borujerdi's pupil. Borujerdi forbade Khomeini to take part in political activities, a ban which ended with Borujerdi's death.

Pepsi fatwa[edit]

In 1955 Borujerdi issued a fatwa making Pepsi Cola illegal in Iran.[12] According to Ruhollah Khomeini, this was because the Pepsi franchise in Iran was held by Habib Sabet,[12] a Baháʼí.[13][14]

Death[edit]

Borujerdi died in Qom on 30 March 1961.[15] The Shah proclaimed three days of mourning and attended a memorial service in his honor.[16]

Personal life and education[edit]

Family[edit]

Borujerdi had two sons and three daughters from his first wife, all but one of whom died in childhood. The one who survived, died due to a difficult giving birth two years after marriage.

He had two sons and two daughters from his second wife (the daughter of Hajj Muhammad Ja'far Roughani Isfahani).

His third wife was his cousin, the daughter of Sayyid ‘Abd al-Wahid Tabataba'i.[17]

One of his sons, Sayyid Muhammad Hasan Tabataba'i Burujirdi, who was born in 1925 in Burujird, was in charge of writing the official verdicts of his father. He died in 1977 in Qom. [18]

Education and academic specialties[edit]

After entering elementary school at the age of seven, Sayyid Husayn's father realized his talent for learning and sent him to Nurbakhsh seminary in Borujerd. At the age of 11 he began his education at the theological schools of his city, under his father Sayed Ali. Then in 1310 (1892–93) he attended the theological school of Isfahan to continue his education. In the ten years that he studied in Isfahan, he completed his sutuh studies and was also granted the level of Ijtihad from his teachers, and began teaching Usul. Around the age of 30, Burujerdi moved from Isfahan to the theological seminary of Najaf, Iraq to continue his education. [5]

In his youth, Borujerdi studied under a number of Shia masters of fiqh such as Sayyid Muhammad Baqir Durchih'i, Mohammad-Kazem Khorasani and Aqa Zia Iraqi, and specialized in fiqh. He studied the fiqahat of all the Islamic schools of thought, not just his own, along with the science of rijal. Though he is known for citing Masumeen to support many of his deductions, Borujerdi is known for elucidating many aspects himself and is an influential fiqh jurist in his own right. He has had a strong influence on Islamic scholars like Morteza Motahhari and Hussein-Ali Montazeri.

Notable students[edit]

- Ruhollah Khomeini

- Mohammad-Reza Golpaygani

- Hossein Vahid Khorasani

- Hussein-Ali Montazeri

- Sayed Ali Khamenei

- Sayyid Ali al-Sistani

- Lotfollah Safi Golpaygani

- Ali Safi Golpaygani

- Mohammad Fazel Lankarani

- Seyed Ali Mirlohi Falavarjani

- Mousa Shubairi Zanjani

- Karamatollah Malek-Hosseini

- Muhammad Taha al-Huwayzi[19][20]

Works authored[edit]

Arabic books[edit]

- Jami' ahadith al-shi'a (31 vol)

- Sirat al-nijat

- Tartib asanid man la yahduruh al-faqih

- Tartib Rijal asanid man la yahduruh al-faqih

- Tartib asanid amali al-saduq

- Tartib asanid al-Khisal

- Tartib asanid 'ilal al-sharayi'

- Tartib asanid tahdhib al-ahkam

- Tartib rijal asanid al-tahdhib

- Tartib asanid thawab al-a'mal wa 'iqab al-a'mal

- Tartib asanid 'idah kutub

- Tartib rijal al-Tusi

- Tartib asanid Rijal al-Kashshi

- Tartib asanid rijal al-najjashi

- Tartib rijal al-fihristayan

- Buyut al-shi'a

- Hashiyah 'ala rijal al-najjashi

- Hashiyah 'ala 'umdat al-talib fi ansab al abi talib

- Hashiyah 'ala manhaj al-maqal

- Hashiyah 'ala wasa'il al-shi'a

- Al-mahdi (a) fi kutub ahl al-sunnah

- Al-athar al-manzumah

- Hashiyah 'ala majma' al-masa'l

- Majma' al-furu'

- Hashiyah 'ala tabsirah al-muta'allimin

- Anis al-muqalladin[21]

Persian Books[edit]

- Tudih al-manasik

- Tudih al-masa'l

- Manasik haj[22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Mottahedeh, Roy, The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran, One World, Oxford, 1985, 2000, p.231

- ^ Davvani, Ali. مفاخر اسلام [Mafakhir Islam] (in Persian). Vol. 12. pp. 69–95.

- ^ Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet, (1985, 2000), p.231

- ^ a b c Hamid Dabashi. Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b c d e Algar, Hamid (1989). "BORŪJERDĪ, ḤOSAYN ṬABĀṬABĀʾĪ". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Davvani, Ali. مفاخر اسلام [Mafakhir Islam] (in Persian). Vol. 12. p. 177.

- ^ Hawza. 43: 3–4–5.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet, (1985, 2000), p.230

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, 1940- (1993). Khomeinism : essays on the Islamic Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91466-7. OCLC 44963924.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet, (1985, 2000), p.237-8

- ^ Sayyid Husain Borujirdi

- ^ a b A.H. Fink (2020). The importance of conspiracy theory in extremist ideology and propaganda (PhD thesis). Leiden University. p. 382. hdl:1887/87359.

- ^ Ruhollah Khomeini (1984). A Clarification Of Questions: An Unabridged Translation Of Resaleh Towzih Al-masael: Unabridged Translation of "Resaleh Towzih Al-Massael". Routledge. ISBN 978-0865318540.

- ^ Abbas Milani (2011). The Shah. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 244. ISBN 978-1403971937.

- ^ "Bourjerdi dies in Iran," The New York Times, 31 March 1961, p. 27.

- ^ Mottahedeh, The Mantle of the Prophet, (1985, 2000), p.240

- ^ Davvani, Ali. مفاخر اسلام [Mafakhir Islam] (in Persian). Vol. 12. p. 538.

- ^ Davvani, Ali. مفاخر اسلام [Mafakhir Islam] (in Persian). Vol. 12. pp. 538–540.

- ^ Al Mahbubah, Ja'far Baqir (2009). Māḍī al-Naǧaf wa-ḥāḍiruhā ماضى النجف وحاضرها [Najaf's past and present] (in Arabic). Vol. 2 (second ed.). Beirut, Lebanon: Dar Al-Adhwa. p. 188.

- ^ سیر مبارزات امام خمینی به روایت ساواک [Seir e mobarezat e imam khomeini be revayat e savak] (in Persian). Vol. 1. p. 45. and Biography of Ayatollah Khamenei the Leader of the Islamic Revolution

- ^ Noor-e-Elm (in Persian). 12: 87–88.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Noor-e-Elm (in Persian). 12: 89.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)