George E. Waring Jr.

George E. Waring Jr. | |

|---|---|

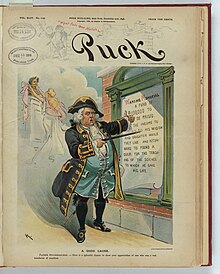

in 1883 | |

| Born | July 4, 1833 Pound Ridge, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1898 (aged 65) New York City, U.S. |

| Monuments | Woodland Cemetery, Stamford Connecticut |

| Occupation(s) | Sanitary engineer, civic reformer |

| Years active | 1865–1898 |

| Known for | Advocate of sewer systems that keep domestic sewage separate from storm runoff |

George E. Waring Jr. (July 4, 1833[1] – October 29, 1898) was an American sanitary engineer and civic reformer. He was an early American designer and advocate of sewer systems that keep domestic sewage separate from storm runoff.

Early life[edit]

Waring was born in Pound Ridge, New York, the son of George E. Waring Sr., a wealthy stove manufacturer. Trained in agricultural chemistry, he began to lecture on agricultural science[where?]. In 1855, he took charge of Horace Greeley's farm at Chappaqua, New York.[2]

Career[edit]

Draining Central Park[edit]

In 1857, Waring was appointed agricultural and drainage engineer for the construction of New York City's Central Park.[2] This effort was considered to be the largest drainage project of its time. Prior to this time, much of the area of the proposed park was a wetland. He designed and supervised construction of the drainage system that created the scenic lakes and ponds of the park.[3] An enthusiastic equestrian, he and his horse "Vixen" would often use the park's construction as jumping obstacles.[4]

Civil War Service[edit]

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Waring resigned from the Central Park project to accept a military commission as major. He departed New York in the early summer, and drilled for a month in Washington DC, occasionally meeting President Lincoln as he reviewed the troops. Waring departed Washington DC on July 4, 1862, and fought at Battle of Blackburn's Ford.[4] He then joined John C. Frémont and headed to St. Louis, where he commanded the Fremont Hussars. His beloved mare Vixen died on campaign in November 1862, near Jefferson City.

Waring acquired a new charger, Ruby, a chestnut described as "a picture of the most abject misery; his hind legs drawn under him; the immense muscles of his hips lying flabby, like a cart-horse’s; his head hanging to the level of his knees, and his under-lip drooping; his eyes half shut, and his long ears falling out sidewise like a sleepy mule’s."[4] Despite appearances, Ruby was an uncommonly good jumper.

He raised six companies of cavalry for the Union side in the State of Missouri. These units were eventually consolidated as the 4th Missouri Cavalry under Waring, who was promoted to the rank of colonel in January 1862. He commanded this regiment throughout the war, principally in the Southwest.[2]

Ogden Farm[edit]

During the 18th century, Newport, Rhode Island's wealthy merchants developed country agricultural estates in the outlying towns. Following the Civil War, with a romanticizing of rural, country and farm life by Andrew Jackson Downing and others, estate farms for the Newport summer colony became widespread. Some of these were "model" farms based upon the latest agricultural practice, engineering and technology. Ogden Farm is such a model farm, named after Edward Ogden of New York City and Newport (1808–1872), whose summer house was on Narragansett Avenue. After Edward Ogden's death, the property became known as the Ogden Farm. In 1867 Colonel Waring settled there to manage the farm. At Ogden Farm, he introduced Jersey cattle into the United States and founded the American Jersey Cattle Club. Waring is known to have laid clay drainage pipe there for field improvement, some of which is still extant. Waring devoted himself to agriculture, cattle breeding and drainage until 1877, when drainage and sanitary engineering became his major preoccupation.[2][5]

In 1876 William Smith patented a jet siphon water closet, an innovation that caught the attention of Waring, who developed the design for larger pieces of sanitary ware (toilets).[6] In 1881, William Paul Gerhard, another historically important sanitary engineer became Waring's chief assistant.[7]

Memphis sewer system[edit]

Memphis, Tennessee had suffered several severe cholera epidemics (1849, 1866, 1873) and yellow fever (1867, 1873, 1878 and 1879), with over 5,000 fatalities in 1878 alone.[8][9] Sanitary conditions in the city were poor, with many domestic wells close by privies and drained by a fetid bayou. Many buildings had standing water underneath because of the poorly-draining clay soil. Civic leaders recognized the need for better drainage and a sewer system that would keep domestic waste away from the wells, although they were wrong in their belief that yellow fever was spread by inadequate sanitation practices. It was, in fact, spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which breeds in stagnant water. The financially strapped city and the state legislature were unable to raise sufficient funds for construction of a conventional combined sewer system, due to the mass exodus of residents for fear of yellow fever. The situation in Memphis aroused the sympathy of the nation and was largely responsible for the creation of the National Board of Health,[10] a predecessor to the United States Public Health Service. The Board sent Waring to Memphis, where he designed what he thought was a system Memphis could afford. Waring's design called for the separation of sewage waste from storm water runoff, an innovation that reduced the size of the pipes required to carry septic sewage. Until this time, this idea had not been used in the United States on a large scale.[11] Memphis constructed a separated sewer system according to Waring's plans, and its era of epidemics came to an end.[12]

New York City[edit]

In 1895,[13] Waring was brought to New York City, where sanitary conditions had become intolerable. Horses were leaving an estimated 2.5 million pounds of manure and 60,000 gallons of urine on the streets every day.[13] Horse carcasses rotted in the streets. Garbage piles reached a foot or two deep,[13][14] cleared only haphazardly by "ragtag army of the unemployed."[13]

Waring began by securing a law requiring horses and carts to be stabled overnight, instead of being left on the street.[13] He established a Street Cleaning Department, a white-uniformed corps of workers wearing pith helmets and pushing wheeled carts tasked with cleaning up city streets .[13] Waring's men cleared a shin-deep accumulation of waste across the city. Horse carcasses were removed from the streets and sold for glue; horse manure was sold for fertilizer.[13] Other refuse was sent to dumps along the waterfront.[13] Waring's crew even removed snow, packing it into trucks and dumping it into the rivers.[13]

The success of Waring's efforts was quick, dramatic and much appreciated by New York citizens. A parade was held for the sanitation works in 1896.[14]

Cuba[edit]

Based on his reputation as one of the most distinguished Americans in the field of sanitary engineering, at the close of the Spanish–American War in 1898 President William McKinley appointed Waring to make a study of the sanitary situation in Cuba. He had previously (1887) designed a sewer system for Santiago, Cuba.[2]

Personal life[edit]

Waring was married three times: first in 1855 to Euphemia Johnston Blunt; second in 1865 to Virginia Clark; and third on July 20, 1898, to Louise Yates of New Orleans.[citation needed]

Soon after his third marriage, while in Cuba Waring contracted yellow fever and died shortly after returning to New York City on October 29, 1898.[15][16] His body was cremated and the ashes were placed in an urn, and buried in the family plot in Stamford, Connecticut.[17]

Legacy[edit]

An avenue in the North Bronx near Pelham Parkway was named in his honor, Waring Avenue. Memphis has a street named for Waring (Waring Road) running from Walnut Grove Road north to Macon Road at Wells Station Road, going through the Berclair neighborhood.[citation needed]

Waring's publications[edit]

- Jersey cattle, being an essay on this breed. Judd, New York, 1872.

- Wedding at Ogden Farm, in Scribners Monthly Illustrated Magazine. May 1876 – October 1876, Scribner and Company, New York, 1876.

- The Handy-Book of Husbandry: A Guide for Farmers, Young and Old. in Scribners Monthly Illustrated Magazine. E.B. Treat & Co., New York.

- Waring's Book of the Farm; Being a Revised Edition of the Handy-Book of Husbandry. A Guide for Farmers. Porter & Coates, Philadelphia, 1877.

- A Farmer’s Vacation, in Reprinted (with additions) from Scribner's Monthly Illustrated Magazine. James R. Osgood & Company, Boston, MA. 1876.

- The Sanitary Condition of City and Country Dwelling Houses. - Sanitation, Household - 1877 - 145 pages.

- Draining for Profit and Draining for Health.

- Whip and Spur.- Boston, Ticknor and Company - 1892 - 245 pages.

- Modern Methods of Sewage Disposal. D. Van Nostrand Co., NY. 1894.

- How to drain a house, practical information for householders. D. Van Nostrand Company, New York.

- Street-cleaning and the Disposal of a City's Wastes. Doubleday and McClure Co., NY 1897, 230 pp.

References[edit]

- ^ R.R. Bowker Company (1898). The publishers weekly, Volume 54. F. Leypoldt. p. 725.

- ^ a b c d e Medico-Legal Society of New York. Obituary, George E. Waring Jr. The Sanitarian – Hygiene, 1898, p. 559.

- ^ Biebighauser, Thomas R. Wetland Drainage, Restoration, and Repair. University Press of Kentucky pp. 5-6.

- ^ a b c Whip and Spur by George E. Waring.

- ^ Murphy House at Ogden Farm.[permanent dead link] United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.

- ^ The Men That Made the Water Closet Reprinted from: Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1994.

- ^ Gerhard, William Paul. The laying-out of cities and towns. Reprinted from Journal of the Franklin Institute 140 (August 1895):90- 99.

- ^ Wrenn, Lynette Boney (1998). Crisis and commission government in Memphis: elite rule in a Gilded Age city (1st ed.). Knoxville: Univ. Tenn. Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0-87-049997-5.

- ^ Sigafoos, Robert Alan. Cotton Row to Beale Street: A business history of Memphis Memphis State Univ. Press (1979) p. 56.

- ^ Smillie, W. G. The National Board of Health, 1879-1883, American Journal of Public Health and The Nation's Health, (1943) 33(8):925-930.

- ^ Jon C. Schladweiler, Tracking Down the Roots of Our Sanitary Sewers: A chronology of sewer history throughout the world, Arizona Water & Pollution Control Association

- ^ A detailed description of Watt's design for the Memphis sewer system and its installation can be found in F.S. Odell, The Sewerage of Memphis with Discussions. Frederick S. Odell, The Sewerage of Memphis with Discussions,, Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, Volume IX (February 1881), pp. 23-52 and Plate IV. See pp. 24-26 for discussion of Colonel Waring's influence on the creation of a separate system in Memphis. See pp 45-52 for George Waring’s rebuttal to criticisms in the Odell article.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sante, Luc (1991). Low Life (2003 ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 48. ISBN 978-0374528997.

- ^ a b Horn, Heather. "The Secret Lives of Garbage Men". The Atlantic Cities. The Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Melosi, Martin V., Garbage in the cities: refuse, reform, and the environment. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Trager, James (2010). The New York Chronology: The Ultimate Compendium of Events, People, and Anecdotes from the Dutch to the Present. HarperCollins. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-062-01860-1.

- ^ The evening world., July 28, 1911, Final Edition, Image 1. Accessed July 4,2019