Ellery Queen

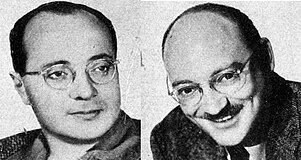

Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee | |

|---|---|

Manfred Lee (left) and Frederic Dannay | |

| Born | Daniel Nathan (Dannay) October 20, 1905 Brooklyn, New York Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky (Lee) January 11, 1905 Brooklyn, New York |

| Died | September 3, 1982 (aged 76) White Plains, New York (Dannay) April 3, 1971 (aged 66) Roxbury, Connecticut (Lee) |

| Alma mater | New York University (Lee) |

| Occupation | Authors |

| Years active | 1929–1971 |

| Spouse |

Rose Koppel, to Dannay

(m. 1975) |

Ellery Queen is a pseudonym created in 1928 by the American detective fiction writers Frederic Dannay (1905–1982) and Manfred Bennington Lee (1905–1971). It is also the name of their main fictional detective, a mystery writer in New York City who helps his police inspector father solve baffling murder cases.[1][2][3] From 1929 to 1971, Dannay and Lee wrote around forty novels and short story collections in which Ellery Queen appears as a character.

Under the pseudonym Ellery Queen, they also edited more than thirty anthologies of crime fiction and true crime. Dannay founded, and for many years edited, the crime fiction magazine Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, which has been published continuously from 1941 to the present. From 1961 onwards, Dannay and Lee commissioned other authors to write thrillers using the pseudonym Ellery Queen, but not featuring Ellery Queen as a character; some such novels were juvenile and were credited to Ellery Queen Jr. They also wrote four novels under the pseudonym Barnaby Ross, which featured the detective Drury Lane.[3][4][5] Several movies, radio shows, and television shows have been based on their works.[6]

Dannay and Lee were cousins, who were better known by their professional names.[2][7] Frederic Dannay was the professional name of Daniel Nathan[8][2] and Manfred Bennington Lee that of Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky.[2][8][5] Since 2013, the complete works of Ellery Queen have been represented by JABberwocky Literary Agency.[9][10]

Personal life of Dannay and Lee[edit]

Manfred Bennington Lee was born as Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky on 11 January 1905 in Brooklyn, New York.[2] He graduated from the New York University with a summa cum laude degree in English in the 1920s.[8] He died on 3 April 1971 in Roxbury, Connecticut.[2][11]

Frederic Dannay was born as Daniel Nathan on 20 October 1905 in Brooklyn, New York.[2][12] He married Rose Koppel, an assistant registrar at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, in 1975.[13] He died on 3 September 1982 in White Plains, New York.[2][14]

Ellery Queen, the pseudonym[edit]

Ellery Queen was created in the fall of 1928 when Dannay and Lee entered a mystery novel writing contest offering a prize of $7500 (equivalent to $133,000 in 2023) jointly sponsored by McClure's magazine and Frederick A. Stokes Company. They decided to use as their collective pseudonym the same name they had given to their detective as they believed readers tended to remember the names of detectives but forget those of their creators. They were informed that they had won the contest, but McClure's magazine went bankrupt and was absorbed by The Smart Set magazine before they received any money.[15][16][17][18]

The Smart Set magazine rejudged the contest and awarded the prize to an entry by the writer Isabel Briggs Myers but in 1929, Frederick A. Stokes Company agreed to publish Dannay and Lee's story under the title The Roman Hat Mystery. Buoyed by its success, they were contracted to write more mysteries and they went on to write a successful series of novels and short stories that lasted 42 years.[15][19][20][21]

During the 1940s, Ellery Queen was probably the most popular American mystery writer.[22][4] More than 150 million copies of Queen's books were sold globally and 'he' remained the best-selling mystery writer in Japan till the end of the 1970s.[23][24]

Many short stories were also published under the Queen name, which were mostly well-received. The novelist and critic Julian Symons called them "as absolutely fair and totally puzzling as the most passionate devotee of orthodoxy could wish" and said they were "composed with wonderful skill"[25] whereas the historian Jaques Barzun said they were "full of ingenious gimmicks and adorned with excellent titles".[26]

Dannay, without much involvement from Lee, founded the crime fiction magazine Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in 1941, and served as its editor-in-chief until his death in 1982. However, they together edited numerous collections and anthologies of crime fiction such as The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes and 101 Years' Entertainment, The Great Detective Stories, 1841–1941. They were awarded the Grand Master Award by the Mystery Writers of America in 1961 for their work under the Ellery Queen pseudonym.[3][15][27]

From 1961 onwards, they allowed the 'Ellery Queen' nom de plume to be used as a house name for several novels written by other authors. None of these novels feature Ellery Queen as a character.[15] Three of them star "the governor's troubleshooter" Micah "Mike" McCall and six of them feature Captain Tim Corrigan of the New York City Police Department. The prominent science-fiction writer Jack Vance wrote three such novels including the 1965 locked room mystery A Room to Die In.[3]

Dannay and Lee remained reticent about their writing methods.[7][28] Novelist and critic H.R.F. Keating wrote, "How actually did they do it? Did they sit together and hammer the stuff out word by word? Did one write the dialogue and the other the narration? ... What eventually happened was that Fred Dannay, in principle, produced the plots, the clues, and what would have to be deduced from them as well as the outlines of the characters and Manfred Lee clothed it all in words. But it is unlikely to have been as clear cut as that."[29]

According to the crime fiction critic Otto Penzler, "As an anthologist, Ellery Queen is without peer, his taste unequalled. As a bibliographer and a collector of the detective short story, Queen is, again, a historical personage. Indeed, Ellery Queen clearly is, after Poe, the most important American in mystery fiction."[30]

British crime novelist Margery Allingham said that Dannay and Lee had "done far more for the detective story than any other two men put together" and critic Anthony Berkeley Cox famously quoted "Ellery Queen is the American Detective Novel".[31][32]

Although Dannay outlived Lee by eleven years, the Ellery Queen nom de plume died with Lee. The last novel featuring the character Ellery Queen, A Fine and Private Place, was published in 1971, the year of Lee's death.[33] However, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine is still in print as of 2023, now published as six "double issues" per year by Dell Magazines.[34]

Barnaby Ross[edit]

In 1932 and 1933, Dannay and Lee wrote four novels using the pseudonym Barnaby Ross featuring Drury Lane, a Shakespearean actor who had retired from the stage due to deafness and is now often consulted as an amateur detective. The novels also feature Inspector Thumm (initially as a member of the New York police, later as a private investigator) and his crime-solving daughter Patience. From the 1940s, republications of the Drury Lane books were mostly under the Ellery Queen name.[15]

In the early 1930s, before their identity as the authors behind Ellery Queen and Barnaby Ross had been made public, Dannay and Lee staged a series of public debates with Lee impersonating Queen and Dannay impersonating Ross, both of them wearing masks to preserve their anonymity. According to H.R.F. Keating, "People said Ross must be the wit and critic Alexander Woollcott and Queen [must be] S.S. Van Dine, creator of the super-snob detective Philo Vance, on whom 'Ellery Queen' was indeed modeled."[29]

In the 1960s, Dannay and Lee allowed the Barnaby Ross name to be used as a pseudonym for a series of historical romance novels by the writer Don Tracy.[15][35]

Fictional style[edit]

The Queen novels are examples of "fair play" mysteries, a subgenre of the whodunit mystery in which the reader obtains the clues along with the detective and the mysteries are presented as intellectually challenging puzzles. These type of novels comprised what would later be known as the Golden age of detective fiction (Usually dated from 1920 to 1940 but some critics include the 1940s and even the 1950s).[33] Mystery writer John Dickson Carr called this subgenre "the grandest game in the world".[36]

The first Ellery Queen book The Roman Hat Mystery established a reliable template: a geographic formula title (The Dutch Shoe Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, etc.); an unusual crime; a complex series of clues and red herrings; multiple misdirected solutions before the final correct solution is revealed, and a cast of supporting characters including Ellery Queen, the detective, Queen's father Inspector Richard Queen and his irascible assistant Sergeant Thomas Velie. What became the best known part of the early Ellery Queen books was the "Challenge to the Reader", a single page near the end of the book, on which Queen, the detective, paused the narrative, directly addressed the reader, declared that they had now seen all the clues needed to solve the mystery, and only one solution was possible. According to Julian Symons, "The rare distinction of the books is that this claim is accurate. These are problems in deduction that do really permit of only one answer, and there are few crime stories indeed of which this can be said... Judged as exercises in rational deduction, these are certainly among the best detective stories ever written."[37]

In many earlier books like The Greek Coffin Mystery and The Siamese Twin Mystery, multiple solutions to the mystery are proposed, a feature that also showed up in later books such as Double, Double and Ten Days' Wonder. Queen's "false solution, followed by the true" became a hallmark of the canon. Another stylistic element in many early books (notably The Dutch Shoe Mystery, The French Powder Mystery and Halfway House) is Queen's method of creating a list of attributes (the murderer is male, the murderer smokes a pipe, etc.) and comparing each suspect to these attributes, thereby reducing the list of suspects to a single name, often an unlikely one.[38][4]

By the late 1930s, when Ellery Queen, the fictional character, had moved to Hollywood to try movie scriptwriting, the tone of the novels changed along with the detective's character. Romance was introduced, solutions began to involve more psychological elements, and the "Challenge to the Reader" vanished. The novels also shifted from mere puzzles to more introspective themes. The three novels set in the fictional New England town of Wrightsville even showed the limitations of Queen's methods of detection. Julian Symons said "Ellery... occasionally lost his father, as his exploits took place more frequently in the small town of Wrightsville... where his arrival as a house guest was likely to be the signal for the commission of one or more murders. Very intelligently, Dannay and Lee used this change in locale to loosen the structure of their stories. More emphasis was placed on personal relationships and less on the details of investigation."[39]

In the 1950s and the 1960s, Dannay and Lee became more experimental, especially in the novels they wrote with other writers. The Player on the Other Side (1963), ghost-written with Theodore Sturgeon, delves more deeply into motive than most Queen novels. And on the Eighth Day (1964), ghost-written with Avram Davidson, is a religious allegory about fascism.[33]

Ellery Queen, the fictional character[edit]

| Ellery Queen | |

|---|---|

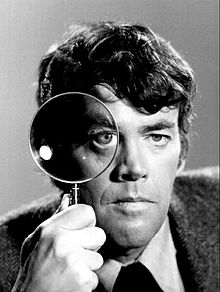

Jim Hutton as Ellery Queen | |

| First appearance | The Roman Hat Mystery |

| Last appearance | A Fine and Private Place |

| Created by | Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee (writing as Ellery Queen) |

| Portrayed by | Donald Cook Eddie Quillan Ralph Bellamy Hugh Marlowe Carleton G. Young Sydney Smith William Gargan Lawrence Dobkin Howard Culver Richard Hart Lee Bowman George Nader Lee Philips Bill Owen Peter Lawford Jim Hutton |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Amateur detective, Author |

| Family | Richard Queen (father) |

| Nationality | American |

Ellery Queen, the fictional character, is the hero of more than thirty novels and several short story collections, written by Dannay and Lee and published under the Ellery Queen pseudonym. He is probably inspired by Philo Vance, the detective created by the writer S.S. Van Dine.[15] According to the critic H.R.F. Keating, "Later the cousins [Dannay and Lee] took a sharper view of Vance, Manfred Lee calling him, with typical vehemence, 'the biggest prig that ever came down the pike'."[29]

As Van Dine had done earlier with Philo Vance, Dannay and Lee gave Ellery Queen an extremely elaborate back story that was rarely mentioned after the first few novels. In fact, Queen goes through several transformations in his personality and his approach to investigation over the course of the series.[1][3]

In the earlier novels, he is a snobbish Harvard-educated intellectual of independent means who wears pince-nez glasses and investigates crimes because he finds them stimulating. He supposedly derives these characteristics from his unnamed late mother, the daughter of an aristocratic New York family, who had married Richard Queen, a bluff and short policeman.[4]

Beginning in the 1938 novel The Four of Hearts, he spends some time working in Hollywood as a screenwriter. Soon, he has a slick façade, is part of Hollywood society and hobnobs comfortably with the wealthy and the famous. Beginning with Calamity Town in 1942, he becomes less of a cypher and more of a human being, often becoming emotionally affected by the people in his cases, and at one point quitting detective work altogether. Calamity Town and some other novels during this period are set in the imaginary town of Wrightsville, where subsidiary characters recur from story to story as Queen relates to the various strata of American society as an outsider.[4]

However, after his Hollywood and Wrightsville periods, he returns to his New York City roots for the rest of his career, and is then seen again as an ultra-logical crime solver who remains distant from his cases. In the very late novels, he often seems a near-faceless, near-characterless persona whose role is purely to solve the mystery. So striking are the differences between the different periods of the Ellery Queen character that Julian Symons advanced the theory that there were two Ellery Queens — an older and younger brother.[40]

Queen is said to be married and the father of a child in the introductions of the first few novels, but this plot line is never developed and he is portrayed as a bachelor in all of his later appearances. Nikki Porter, who acts as Queen's secretary and is something of a love interest, is first introduced in the radio series The Adventures of Ellery Queen in 1939. Her first appearance in a written story is on the final pages of the 1943 novel There Was an Old Woman, when a character with whom Queen has had some flirtatious moments suddenly announces that she will change her name to Nikki Porter and will work as Queen's secretary. Nikki Porter appears sporadically thereafter in the novels and short stories, linking the character from radio and movies to the written canon.[3]

Paula Paris, an agoraphobic gossip columnist, is linked romantically with Queen in the 1938 novel The Four of Hearts and in some short stories in the 1940s but does not appear in the radio series or films and soon vanishes from the books. Queen is not given any serious romantic interests after Nikki Porter and Paula Paris disappear from the books.[3]

The Queen household, an apartment on West 87th street in New York City, is shared by Ellery Queen and his father Richard Queen. It also contains a houseboy named Djuna in the earlier novels. Possibly of Roma origin, Djuna appears periodically in the canon, apparently ageless and family-free, in a supporting role as cook, receiver of parcels, valet, and occasional comedy relief. He is the protagonist in most of the juvenile novels ghost-written under the pseudonym Ellery Queen Jr.[3][15]

In other media[edit]

Radio[edit]

The radio series The Adventures of Ellery Queen was broadcast on several networks from 1939 to 1948 with the lead role played by Hugh Marlowe (1939–1940), Carleton Young (1942–1943), Sydney Smith (1943–1947), Lawrence Dobkin (1947–48) and Howard Culver (1948). All episodes in this series were paused just before the end to allow a panel of celebrities a chance to solve the mystery.[41][42][43][44] Some of the surviving scripts were published for the first time in the 2005 book The Adventure of the Murdered Moths.[45]

Between 1965 and 1967, Ellery Queen's Minute Mysteries were broadcast as radio fillers. They began with the radio announcer Bill Owen saying "This is Ellery Queen..." and contained a short one-minute case.[15][46]

Television[edit]

Some of the scripts of the television series The Adventures of Ellery Queen (1950–1951 on Dumont, 1951-1952 on ABC) were written by Helene Hanff, best known for her 1970 novel 84, Charing Cross Road.[47] Shortly after the series began, Richard Hart, who played Queen, died and was replaced by Lee Bowman.[48]

In 1954, Norvin Productions produced the syndicated series Ellery Queen, Detective with Hugh Marlowe as the title character. Episodes from this series were broadcast on many local American networks and in United Kingdom between 1954 and 1959 under various titles like Mystery is my Business, Crime Detective and New Adventures of Ellery Queen.[49]

George Nader played Queen in NBC's The Further Adventures of Ellery Queen (1958–1959), but was replaced by Lee Philips in the final episodes.[50]

Peter Lawford starred as Ellery Queen in the 1971 television film Ellery Queen: Don't Look Behind You (a loose adaptation of the 1949 novel Cat of Many Tails). Harry Morgan played Inspector Richard Queen in this film, but he is described as Ellery Queen's uncle (perhaps to account for the fact that Morgan was only eight years Lawford's senior, or to account for Lawford's British accent).[51]

The 1975 television movie Ellery Queen (aka Too Many Suspects, a loose adaptation of the 1965 novel The Fourth Side of the Triangle) led to the 1975–1976 television series of the same name starring Jim Hutton in the title role with David Wayne as his widowed father Richard Queen. This series was developed by Richard Levinson and William Link, who later won a Special Edgars Award for creating it and Columbo.[52] It was done as a period piece set in New York City in 1946–1947.[53] Sergeant Velie, Inspector Queen's assistant, regularly appeared in it; he had previously appeared in the novels and the radio series, but had not been seen regularly in any of the previous television versions. Each episode contained a "Challenge to the Viewer" in which Queen broke the fourth wall to go over the facts of the case and encouraged the audience to try to solve the mystery before the correct solution was revealed. Eve Arden, George Burns, Joan Collins, Roddy McDowall, Milton Berle, Guy Lombardo, Rudy Vallée, and Don Ameche were among the celebrities featured in this series.[54]

In 2011, in the crime series Leverage's episode The 10 Li'l Grifters Job, Timothy Hutton's character Nate Ford appears at a murder mystery party dressed as Ellery Queen, in a homage to the actor's late father Jim Hutton.[55]

Films[edit]

- The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935) - Donald Cook as Ellery Queen, Guy Usher as Inspector Queen (based on The Spanish Cape Mystery)[56]

- The Mandarin Mystery (1936) - Eddie Quillan as Ellery Queen, Wade Boteler as Inspector Queen (loosely based on The Chinese Orange Mystery)[57]

- Ellery Queen, Master Detective (1940) - Ralph Bellamy as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen (very loosely based on The Door Between)[58]

- Ellery Queen's Penthouse Mystery (1941) - Ralph Bellamy as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen[59]

- Ellery Queen and the Perfect Crime (1941) - Ralph Bellamy as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen (loosely based on The Devil To Pay)[60]

- Ellery Queen and the Murder Ring (1941) - Ralph Bellamy as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen (loosely based on The Dutch Shoe Mystery)[61]

- A Close Call for Ellery Queen (1942) - William Gargan as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen[62]

- A Desperate Chance for Ellery Queen (1942) - William Gargan as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen

- Enemy Agents Meet Ellery Queen (1942) - William Gargan as Ellery Queen, Margaret Lindsay as Nikki Porter, Charley Grapewin as Inspector Queen

- La Décade prodigieuse (1971) (English title: Ten Days' Wonder) - directed by Claude Chabrol and starring Anthony Perkins and Orson Welles. There is no character named Ellery Queen but Michel Piccoli plays Paul Regis, the detective (Based on Ten Days' Wonder)[63]

- Haitatsu sarenai santsu no tegami (1979) (English title: The Three Undelivered Letters) - directed by Yoshitarō Nomura (based on Calamity Town but not containing Queen or any other detective)[64]

Theater[edit]

In 1936, Dannay and Lee, in collaboration with playwright Lowell Brentano, wrote the play Danger, Men Working. The production never made it to Broadway, closing after a few performances in Baltimore and Philadelphia.[15]

In 1949, novelist and playwright William Roos adapted the 1938 novel The Four of Hearts for stage, although it is not known if it was ever performed.[65]

In 2016, American playwright Joseph Goodrich adapted the 1942 novel Calamity Town for stage. The play premiered at the Vertigo Theatre in Calgary, Alberta on January 23, 2016.[66]

Comic books and graphic novels[edit]

Ellery Queen appears as a character in some issues of Crackajack Funnies beginning in 1940, a four issue series by Superior Comics in 1949, two issues of a short-lived series by Ziff Davis in 1952, and three comics published by Dell in 1962.[67]

In February 1990, Queen was used as a guest star by the comic book writer Mike W. Barr in the ninth issue of the magazine Maze Agency in the story titled The English Channeler Mystery: A Problem in Deduction.[68]

In July 1996, Queen, the character, was highlighted in the Gosho Aoyoma's Mystery Library section of volume 11 of the Detective Conan manga, a section of the series in which Aoyoma introduces a detective (or occasionally a villain) from mystery literature. A character also stated that he preferred Queen, the author, to Arthur Conan Doyle in volume 12 of the manga.[69]

Board games and jigsaw puzzles[edit]

Ellery Queen's name was attached to many games and puzzles including (Ellery Queen's Great Mystery Game) Trapped in 1956, The Case of the Elusive Assassin by Ellery Queen in 1967,[70] Ellery Queen: The Case of His Headless Highness in 1973, Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine Game in 1986 and a VCR-based game called Ellery Queen's Operation: Murder (loosely based on The Dutch Shoe Mystery) in 1986.[71]

Stamps[edit]

Queen, the character, was one of the twelve fictional detectives featured on a series of stamps issued by Nicaragua in 1973 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Interpol[72] and on a similar series issued by San Marino in 1979.[73]

Awards and honors[edit]

'Ellery Queen' received the following Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America:

- 1946: Best Radio Drama (tied with Mr and Mrs North)[74]

- 1950: Special Edgar Award for ten years' service through Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

- 1961: Grand Master Edgar Award

- 1969: Special Edgar Award on the 40th anniversary of the publication of The Roman Hat Mystery

They were also runners-up for the Edgar in the following categories:

- 1962: Best Short Story (Ellery Queen 1962 Anthology)

- 1964: Best Novel (The Player on the Other Side)

The Mystery Writers of America established the Ellery Queen Award in 1983 "to honor writing teams and outstanding people in the mystery-publishing industry".[75]

Bibliography[edit]

Novels[edit]

By Dannay and Lee[edit]

Unless noted, all these titles feature Ellery Queen and Inspector Richard Queen as characters.[15][33]

- The Roman Hat Mystery—1929

- The French Powder Mystery—1930

- The Dutch Shoe Mystery—1931

- The Greek Coffin Mystery—1932

- The Egyptian Cross Mystery—1932

- The American Gun Mystery—1933

- The Siamese Twin Mystery—1933

- The Chinese Orange Mystery—1934

- The Spanish Cape Mystery—1935

- Halfway House—1936

- The Door Between—1937

- The Devil to Pay—1938

- The Four of Hearts—1938

- The Dragon's Teeth aka The Virgin Heiresses—1939

- Calamity Town—1942

- There Was an Old Woman aka The Quick and the Dead—1943

- The Murderer Is a Fox—1945

- Ten Days' Wonder—1948

- Cat of Many Tails—1949

- Double, Double—1950

- The Origin of Evil—1951

- The King Is Dead—1952

- The Scarlet Letters—1953

- The Glass Village—1954 (neither Ellery Queen nor Inspector Queen appear)

- Inspector Queen's Own Case—1956 (Ellery Queen does not appear)

- The Finishing Stroke—1958

- The Player on The Other Side—1963 (ghost-written with Theodore Sturgeon)

- And on the Eighth Day—1964 (ghost-written with Avram Davidson)

- The Fourth Side of the Triangle—1965 (ghost-written with Avram Davidson)

- Face to Face—1967

- The House of Brass—1968 (ghost-written with Avram Davidson) (very minimal appearance by Ellery Queen)

- Cop Out—1969 (neither Ellery Queen nor Inspector Queen appear)

- The Last Woman in His Life—1970

- A Fine and Private Place—1971

By other authors[edit]

All ghostwriters are identified where known.[15] All titles were edited and supervised by Lee except The Blue Movie Murders (1972), which was edited and supervised by Dannay after Lee's death. None of them feature Ellery Queen or Inspector Richard Queen as characters.

Non-Series[edit]

- Dead Man's Tale (1961) by Stephen Marlowe

- Death Spins The Platter (1962) by Richard Deming

- Wife Or Death (1963) by Richard Deming

- Kill As Directed (1963) by Henry Kane

- Murder With A Past (1963) by Talmage Powell

- The Four Johns (1964) by Jack Vance

- Blow Hot, Blow Cold (1964) by Fletcher Flora

- The Last Score (1964) by Charles W. Runyon

- The Golden Goose (1964) by Fletcher Flora

- A Room To Die In (1965) by Jack Vance

- The Killer Touch (1965) by Charles W. Runyon

- Beware the Young Stranger (1965) by Talmage Powell

- The Copper Frame (1965) by Richard Deming

- Shoot the Scene (1966) by Richard Deming

- The Madman Theory (1966) by Jack Vance

- Losers, Weepers (1966) by Richard Deming

- The Devil's Cook (1966) by Fletcher Flora

- Guess Who's Coming To Kill You? (1968) by Walt Sheldon

- Kiss And Kill (1969) by Charles W. Runyon

Featuring Tim Corrigan[edit]

- Where Is Bianca? (1966) by Talmage Powell

- Why So Dead? (1966) by Richard Deming

- Which Way To Die? (1967) by Richard Deming

- Who Spies, Who Kills? (1967) by Talmage Powell

- How Goes The Murder? (1967) by Richard Deming

- What's In The Dark? (1968) by Richard Deming

Featuring Mike McCall (Troubleshooter series)[edit]

- The Campus Murders (1969) by Gil Brewer

- The Black Hearts Murder (1970) by Richard Deming

- The Blue Movie Murders (1972) by Edward Hoch

Novellas[edit]

By Dannay and Lee

- The Lamp of God (1935) (first published as House of Haunts in the Detective Story Magazine in 1935, collected in the short story collection The New Adventures of Ellery Queen in 1940, and published as a standalone book in 1950)

Short story collections[edit]

By Dannay and Lee.

- The Adventures of Ellery Queen—1934

- The New Adventures of Ellery Queen—1940 (contains The Lamp of God)

- The Case Book of Ellery Queen—1945 (reprints five stories from the two previous collections but also includes three new radio scripts)

- Calendar of Crime—1952

- QBI: Queen's Bureau of Investigation—1955

- Queens Full—1966

- QED: Queen's Experiments In Detection—1968

- The Best Of Ellery Queen—1985 (edited by Francis M. Nevins)

- The Tragedy Of Errors—Crippen & Landru, 1999 (includes a previously unpublished synopsis of a Queen novel written by Dannay and all of the previously uncollected short stories)

- The Adventure of the Murdered Moths and Other Radio Mysteries—Crippen & Landru, 2005

Collections which only contain previously collected short stories are excluded, such as More Adventures of Ellery Queen (1940).

Juvenile novels as Ellery Queen Jr.[edit]

Manfred Lee commissioned the writers Samuel Duff McCoy and James Holding to write juvenile novels under the pseudonym Ellery Queen Jr. but they further 'sub-ghosted' the writing "arousing the ire of Lee" and "making establishing authorship even worse".[15][76] All the novels with a color in their title star Djuna, Queen's houseboy. The other two star Gulliver Queen, Queen's nephew.

Ghosted by Samuel Duff McCoy and sub-ghosted by Frank Belknap Long[edit]

- The Black Dog Mystery – 1941

- The Golden Eagle Mystery – 1942

Ghosted by Samuel Duff McCoy and sub-ghosted by Harold Montanye[edit]

- The Green Turtle Mystery – 1944

- The Red Chipmunk Mystery – 1946

- The Brown Fox Mystery – 1948

- The White Elephant Mystery – 1950

- The Yellow Cat Mystery – 1952

- The Blue Herring Mystery – 1954

Ghosted by James Holding[edit]

- The Mystery of the Merry Magician – 1954 (sub-ghosted by Joseph Greene)

- The Mystery of the Vanished Victim – 1954 (sub-ghosted by Paul S. Newman)

- The Purple Bird Mystery – 1966 (unknown if sub-ghosted)

Novelizations[edit]

- The Adventure of the Murdered Millionaire (1941) (novelization of a radio play broadcast on June 18, 1939)[77]

- The Last Man Club (1941) (novelization of a radio play broadcast on June 25, 1939)[78]

- Ellery Queen, Master Detective (1941) aka The Vanishing Corpse (1968) (novelization of the movie of the same name, which was loosely based on the novel The Door Between (1937) )

- The Penthouse Mystery (1941) (novelization of the movie Ellery Queen's Penthouse Mystery (1941) )

- The Perfect Crime (1942) (novelization of the movie Ellery Queen and the Perfect Crime (1941), which was loosely based on the novel The Devil to Pay (1938) )

- A Study in Terror aka Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper (1966) (novelization of the movie of the same name, mostly written by Paul W. Fairman with Ellery Queen added as a character by Dannay and Lee in the framing story)

Magazines[edit]

- Mystery League—1933

- Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine—1941 onwards

Novels as Barnaby Ross[edit]

By Dannay and Lee[edit]

- The Tragedy Of X—1932

- The Tragedy Of Y—1932

- The Tragedy Of Z—1933

- Drury Lane's Last Case—1933

By Don Tracy[edit]

- Quintin Chivas – 1961

- The Scrolls of Lysis – 1962

- The Duke of Chaos – 1962

- The Cree from Minataree – 1964

- Strange Kinship – 1965

- The Passionate Queen – 1966

Anthologies and collections edited[edit]

- Challenge to the Reader—1938

- 101 Years' Entertainment, The Great Detective Stories, 1841–1941—1941

- Sporting Blood: The Great Sports Detective Stories—1942

- The Female of the Species: Great Women Detectives and Criminals—1943

- The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes—1944

- The Best Stories from Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine—1944

- Dashiell Hammett: The Adventures of Sam Spade and Other Stories—1944

- Rogues' Gallery: The Great Criminals of Modern Fiction—1945

- To The Queen's Taste: The First Supplement to 101 Years' Entertainment, Consisting of the Best Stories Published in the First Five Years of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine—1946

- The Queen's Awards, 1946—1946

- Dashiell Hammett: The Continental Op—1945

- Dashiell Hammett: The Return of the Continental Op—1945

- Dashiell Hammett: Hammett Homicides—1946

- Murder By Experts—1947

- The Queen's Awards, 1947—1947

- Dashiell Hammett: Dead Yellow Women—1947

- Stuart Palmer: The Riddles of Hildegarde Withers—1947

- John Dickson Carr: Dr. Fell, Detective, and Other Stories—1947

- Roy Vickers: The Department of Dead Ends—1947

- Margery Allingham: The Case Book of Mr. Campion—1947

- 20th Century Detective Stories—1948

- The Queen's Awards, 1948—1948

- Dashiell Hammett: Nightmare Town—1948

- O. Henry: Cops and Robbers—1947

- The Queen's Awards, 1949—1949

- The Literature of Crime: Stories by World-Famous Authors—1950

- The Queen's Awards, Fifth Series—1950

- Dashiell Hammett: The Creeping Siamese—1950

- Stuart Palmer: The Monkey Murder and Other Stories—1950

and many more

Critical works[edit]

- The Detective Short Story: A Bibliography—1942

- Queen's Quorum: A History of the Detective-Crime Short Story As Revealed by the 100 Most Important Books Published in this Field Since 1845—1951

- In the Queen's Parlor, and Other Leaves from the Editor's Notebook—1957

True crime[edit]

Collections of true crime stories, which were written by Lee alone and originally published in The American Weekly magazine.

- Ellery Queen's International Case Book (1964)

- The Woman in the Case (1967)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Wheat, Carolyn (June 2005). "The Last Word The Real Queen(s) of Crime". Clues: A Journal of Detection. 23 (4): 87–90. doi:10.3200/CLUS.23.4.87-90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Ellery Queen". Britannica .com. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nevins, Francis M. (1974). Royal bloodline: Ellery Queen, author and detective. Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0892964963.

- ^ a b c d e Symons, Julian (1981). Great detectives: Seven Original Investigations. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810909786.

- ^ a b Pennywark, Leah (1 July 2018). "Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and the Postpulp: From Modern to Postmodern". The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies. 9 (2): 220–244. doi:10.5325/jmodeperistud.9.2.0220. JSTOR 10.5325/jmodeperistud.9.2.0220. S2CID 203528158. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- https://archive.org/details/Ellery_Queen_DuMont

- https://archive.org/details/theAdventuresOfElleryQueen-DeathSpinsAWheel1951

- https://archive.org/details/theAdventuresOfElleryQueen-MurderToMusic1951

- https://archive.org/details/theAdventuresOfElleryQueen-BuckFever1952

- https://archive.org/details/theAdventuresOfElleryQueen-ManWhoEnjoyedDeath1951

- ^ a b Goodrich, Joseph (2012). Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen 1947-1950. Perfect Crime Books. ISBN 978-1-935797-38-8.

- ^ a b c Lee, Rand B. (29 June 2016). "The Story Is the Thing". Retrieved 26 June 2023.

In the 1920s, when Dad applied to New York University as Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky..... change his name from Emanuel Lepofsky to Manfred Lee. (Eventually, Dad's father and sisters adopted "Lee" as their surnames; and Dad's cousin and future writing partner changed his name from Daniel Nathan to Frederic Dannay.)

- ^ Sercu, Kurt. "Copyright information". Ellery Queen, a website on deduction. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Ellery Queen – JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc". awfulagent.com. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Tomasson, Robert E. (1971-04-04). "Manfred B. Lee Is Dead at 65; One of 'Ellery Queen Authors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ Sercu, Kurt. "Whodunit?: a serial of aliasses - page 2 - Boyhood". Ellery Queen, a website on deduction. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Dannay, Rose Koppel (7 February 2016). My Life With Ellery Queen: A Love Story. Perfect Crime Books. ISBN 978-1-935797-66-1.

- ^ Gaiter, Dorothy J. (1982-09-05). "FREDERIC DANNAY, 76, CO-AUTHOR OF ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERIES, DIES". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nevins, Francis M. (2013). The Art of Detection: The Story of how Two Fractious Cousins Reshaped the Modern Detective Novel. Perfect Crime Books. ISBN 978-1935797470.

- ^ "McClure's magazine v.61 no.2 Aug. 1928". HathiTrust. hdl:2027/uva.x030751674. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ "Books and Authors". The New York Times. 12 August 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ Blottner, Gene (2011). Columbia Pictures Movie Series, 1926-1955: The Harry Cohn Years. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786433537.

- ^ Queen, Ellery (1929). The Roman Hat Mystery. Frederick A. Stokes Company.

- ^ Norris, J. F. (2012-12-01). "Pretty Sinister Books: The Enigma of the New McClure's Mystery Contest". Pretty Sinister Books. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ "Whodunit? Theydunit, the Team of Dannay and Lee; THE GLASS VILLAGE. By Ellery Queen. 281 pp. Boston: Little, Brown & Co. $3.50". The New York Times. 15 August 1954. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ Herbert, Rosemary (2003). Herbert, Who's Who in Crime, p.161. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195157611. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ Grossberger, Lewis (1978-03-16). "Ellery Queen". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ Image: Dannay and Lee, 1967

- ^ Symons, Julian (1993). Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel (3rd ed.). Mysterious Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0892964963.

- ^ Barzun, Jaques; Taylor, Wendell Hertig (1989). A Catalogue of Crime (2nd ed.). Harper & Row. p. 665. ISBN 9780060157968.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (1988-03-05). "Ellery Queen's 'Double Lives'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Shenker, Israel (1969-02-22). "Ellery Queen Won't Tell How It's Done". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- ^ a b c Keating, H.R.F. (1989). The Bedside Companion to Crime. New York: Mysterious Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-89296-416-2.

- ^ Roseman, Mill; Penzler, Otto (June 7, 1977). Detectionary: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Characters in Mystery Fiction. Overlook Press.

- ^ "Ellery Queen". World's Best Detective, Crime, and Murder Mystery Books. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ "Queen, Ellery | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ a b c d Hubin, Allen J. (1984). Crime Fiction, 1749-1980: A Comprehensive Bibliography. Garland. ISBN 0-8240-9219-8.

- ^ "Current Issue". Ellery Queen. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms: The Names Behind the Names. BCA. p. 142.

- ^ Carr, John Dickson (1991). Greene, Douglas G. (ed.). The Door to Doom. International Polygonics Ltd. ISBN 978-1558821026.

- ^ Symons, Julian (1993). Bloody murder; from the detective story to the crime novel (3rd ed.). Mysterious Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0892964963.

- ^ Andrews, Dale (2011-11-08). "If It's Tuesday This Must Be Belgium". Washington, D.C.: SleuthSayers.

- ^ Symons, Julian (1972). Bloody murder; from the detective story to the crime novel (1st ed.). London: Faber and Faber. pp. 149–150. ISBN 0-571-09465-1.

- ^ Symons, Julian (1981). Great detectives: Seven Original Investigations. Abrams. pp. 66–70. ISBN 978-0810909786.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3.

- ^ Nevins, Francis M.; Grams, Martin Jr. (2002). The Sound of Detection: Ellery Queen's Adventures in Radio (2nd ed.). OTR Publishing. ISBN 0-9703310-2-9.

- ^ Harmon, Jim (1967). The great radio heroes. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday. pp. 145–148.

- ^ "Ellery Queen's radio plays - page 1 - Season 1 (part 1)". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ The Adventure of the Murdered Moths and Other Radio Mysteries. Crippen & Landru. 2005. ISBN 9781932009156.

- ^ "Ellery Queen's radio plays - page 13 - Minute mysteries". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (1997-04-11). "Helene Hanff, Wry Epistler Of '84 Charing,' Dies at 80". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ "CTVA Crime - "The Adventures of Ellery Queen" (Dumont/ABC) Richard Hart/Lee Bowman". ctva.biz. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "CTVA Crime "Ellery Queen, Detective" (TPA)(1954) starring Hugh Marlowe". ctva.biz. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "CTVA US Crime - "The Adventures of Ellery Queen" (NBC)(1958-59) George Nader/Lee Phillips". ctva.biz. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "Ellery Queen Don't Look Behind You (1971)".

- ^ The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network TV Shows, 1946–present, Brooks and Marsh, 1979, ISBN 0-345-28248-5

- ^ Multiple sources:

- ^ "CTVA US Crime - "Ellery Queen" (Universal/NBC)(1975-76) Jim Hutton, David Wayne". ctva.biz. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ LisaM (2011-07-04). "Review: Leverage, S4, E2 - "The 10 Li'l Grifters Job" - Your Entertainment Corner". Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "The Spanish Cape Mystery". 1935.

- ^ "The Mandarin Mysterydate=29 November 2018". 1936 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Kill as directed: Other Media part 5 ...movies (1)". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ Ellery Queen's Penthouse Mystery (1941), retrieved 2023-09-28

- ^ Ellery Queen And The Perfect Crime (1941), retrieved 2023-09-28

- ^ Scott Lord Mystery. "Ellery Queen and the Murder Ring (Hogan, 1941)". youtube. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Close Call For Ellery Queen (1942), retrieved 2023-09-28

- ^ Canby, Vincent (1972-04-27). "Screen: Chabrol Misses:' Ten Days' Wonder' Has Orson Welles in Lead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ Nomura, Yoshitarô (1980-12-05), Haitatsu sarenai santsu no tegami (Drama, Mystery), Shin Saburi, Nobuko Otowa, Mayumi Ogawa, Shochiku, retrieved 2023-09-25

- ^ Lachman, Marvin (2014). The villainous stage : crime plays on Broadway and in the West End. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9534-4. OCLC 903807427.

- ^ Hobson, Louis B. (2016-01-29). "Vertigo brings Ellery Queen to Calgary stage with Calamity Town". Calgary Herald.

- ^ "Kill as directed: Other Media part 8 ...comics (1)". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "The Maze Agency #9 - The English Channeler Mystery (Issue)". Comic Vine. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "Detective Picture Book - Detective Conan Wiki". www.detectiveconanworld.com. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "Amazon.com: The Case of the Elusive Assassin - An Ellery Queen Mystery Game - Ideal 1967 : Toys & Games". www.amazon.com.

- ^ "Kill as directed: Other Media part 11 ... games". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "Philatelic web page accessed September 29, 2007". Trussel.com. 1972-11-13. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ "Philatelic Web site accessed September 29, 2007". Trussel.com. 1979-07-12. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ Broadcasting. July 15, 1946. p. 91

- ^ "Mystery Writers of America website, accessed September 29 2007". Archived from the original on February 26, 2008.

- ^ "Queen's Bureau of Investigation: the Casebook - page 16". queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-24.

- ^ "The Adventure of the Murdered Millionaire - Q.B.I." queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "The Last Man Club - Q.B.I." queen.spaceports.com. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

External links[edit]

- Ellery Queen movies in the public domain

- Ellery Queen radio shows in the public domain

- Finding aid to Frederic Dannay papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Finding aid to Manfred Lee papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Ellery Queen Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- "Frederic Dannay". Find a Grave.

- "Manfred B. Lee". Find a Grave.